We’ve already discussed how the Israel-Hamas war is the latest conflict where people are poring over social media and news channels looking for updates on what, exactly, is happening. After all, whether it’s news about our neighborhoods or communities on the other side of the world, the web is where we go to find updates.

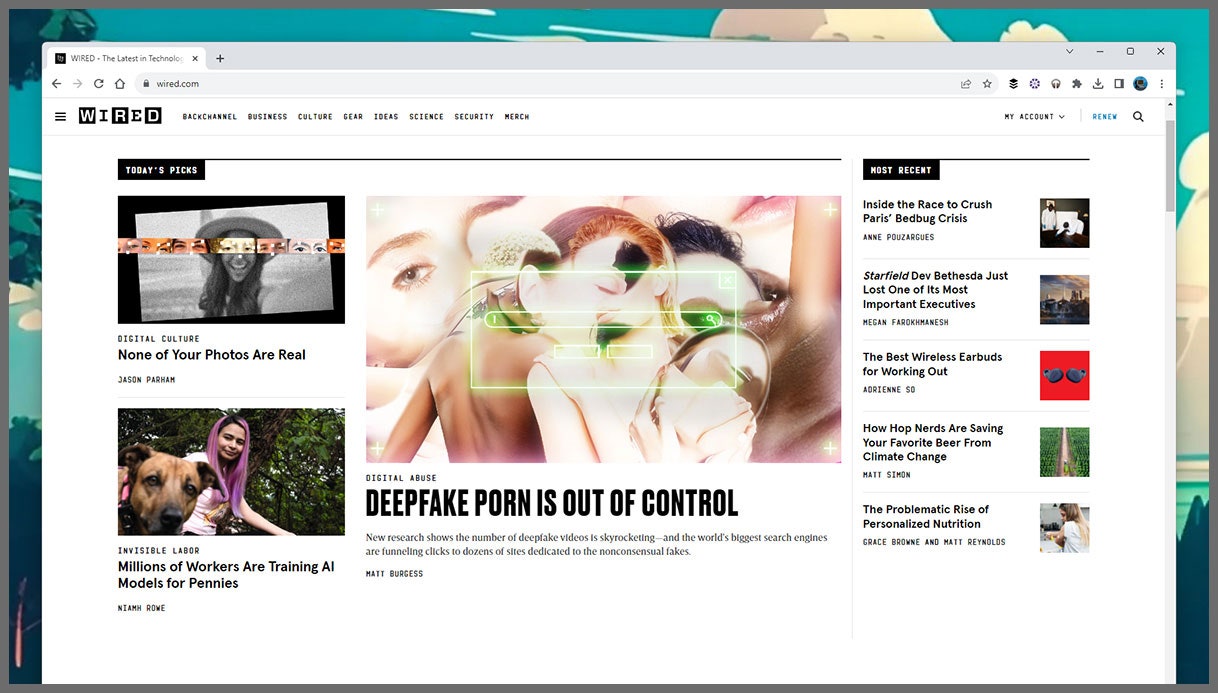

And it’s another reminder that misinformation is often big business, and it’s everywhere: fake news and fabrications, half-truths and obfuscations, and flat-out lies and propaganda. The rise in AI-powered deep fakes has only made the problem worse and increased the amount of untrustworthy content out there.

So is it actually still possible to filter truth from lies online? We don’t yet have a foolproof way of checking—perhaps that’s a task AI could be trained on next—but there are ways to limit the likelihood of being fooled.

Some online sources are clearly more reputable than others: It’s right to be more skeptical about a post by an unknown X user than it is about something from The New York Times or The Washington Post (or WIRED). That’s not to say citizen journalism can’t be useful, because it absolutely can, but be wary of taking it at face value.

It’s not just the source that’s important, it’s the number of sources. Like Bernstein and Woodward, you need to get information backed up and verified by more than one source whenever possible. If you’re looking at a video of an event, for example, look for more recordings from other people, taken from different angles.

If you’re not sure about a particular source, check its history—which is fairly easy to do on social media. Does their most recent post match up with what they’ve posted before? Are they posting a lot of generic content that can’t really be authenticated? How many followers do they have, and how are they interacting with them? These can all be useful factors to consider.

As well as checking the sources of particular stories, photos, and videos, examine the context around them. You can look at whether a video clip is one of a series, for example, or something that seems to have appeared out of nowhere.

Context can extend to whatever the content is showing. If it’s a demonstration, for example, check to see if there’s any other record of it elsewhere on the web and ask a few questions—do the photos and videos match up with where they’re supposed to have been recorded? Are there any pieces of evidence (like police uniforms) that tell you where this is happening?

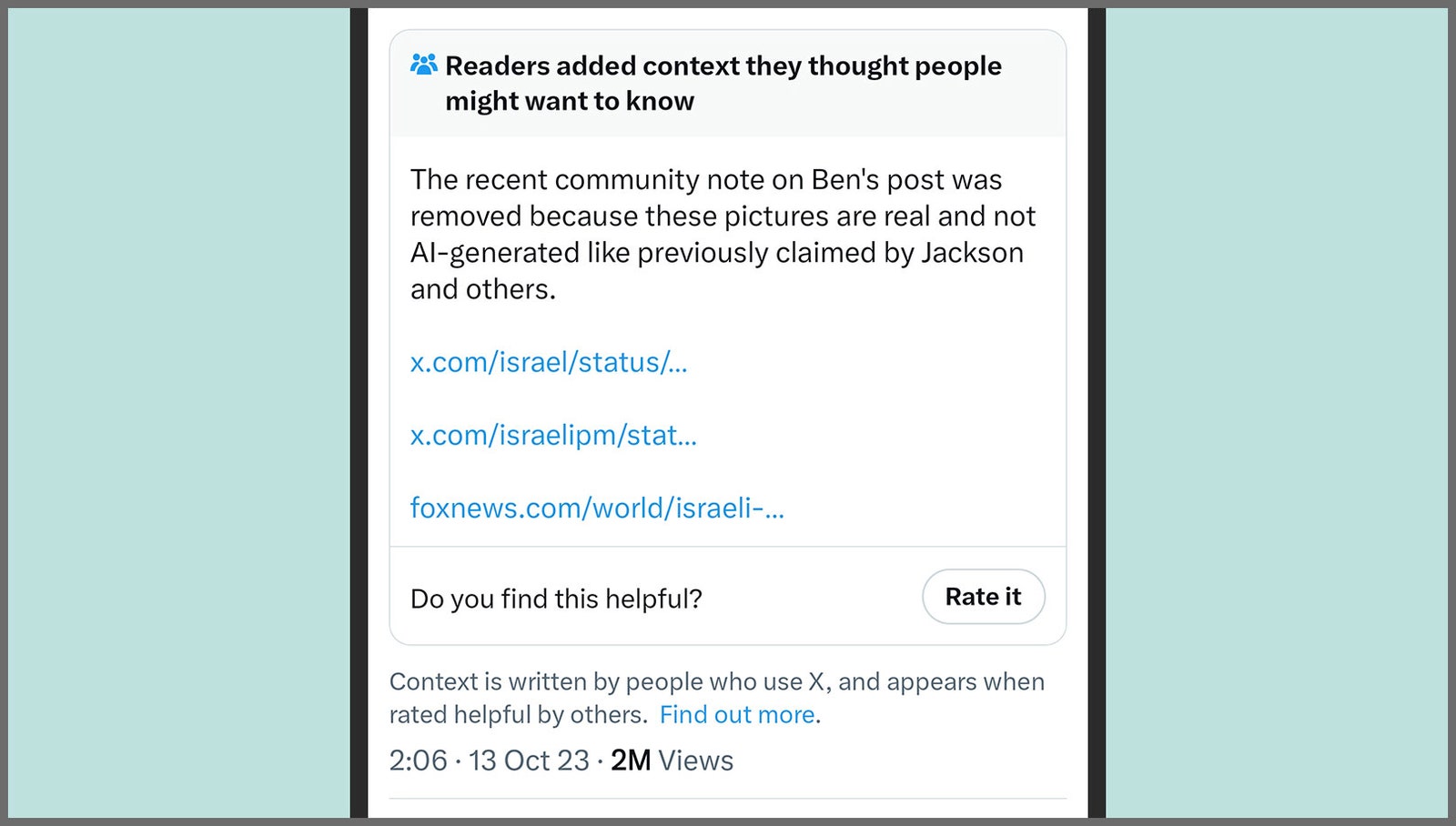

Sometimes there are context tools built into the platforms themselves: You might see false information warnings on Facebook, for example, if a post has been flagged by other users. You might also see what are called community notes attached to posts on X (formerly Twitter), adding extra context about what has been posted. These can be useful signals to consider, though they’re not infallible.

Fake news is often designed to spread as quickly as possible: If something is shocking, inflammatory, or surprising, we’re more likely to pass it on to other people. On social media especially, that can quickly mean inaccurate content starts trending, which of course means it’s then shared by even more people.

With that in mind, look for posts that seem engineered to go viral—to provoke a reaction—rather than to provide information. Misinformation and fake news will often come without any real context attached, such as a source, a location, or an accompanying link that directs you to something similar (like a longer version of the same video or a related story).

Be particularly cautious with posts and media that are furthering a particular cause or course of action. Sometimes a little bit of cynicism is all you need—and sometimes you just need to take a beat and evaluate what you’re looking at again, rather than instantly assuming it’s correct and sharing it elsewhere.

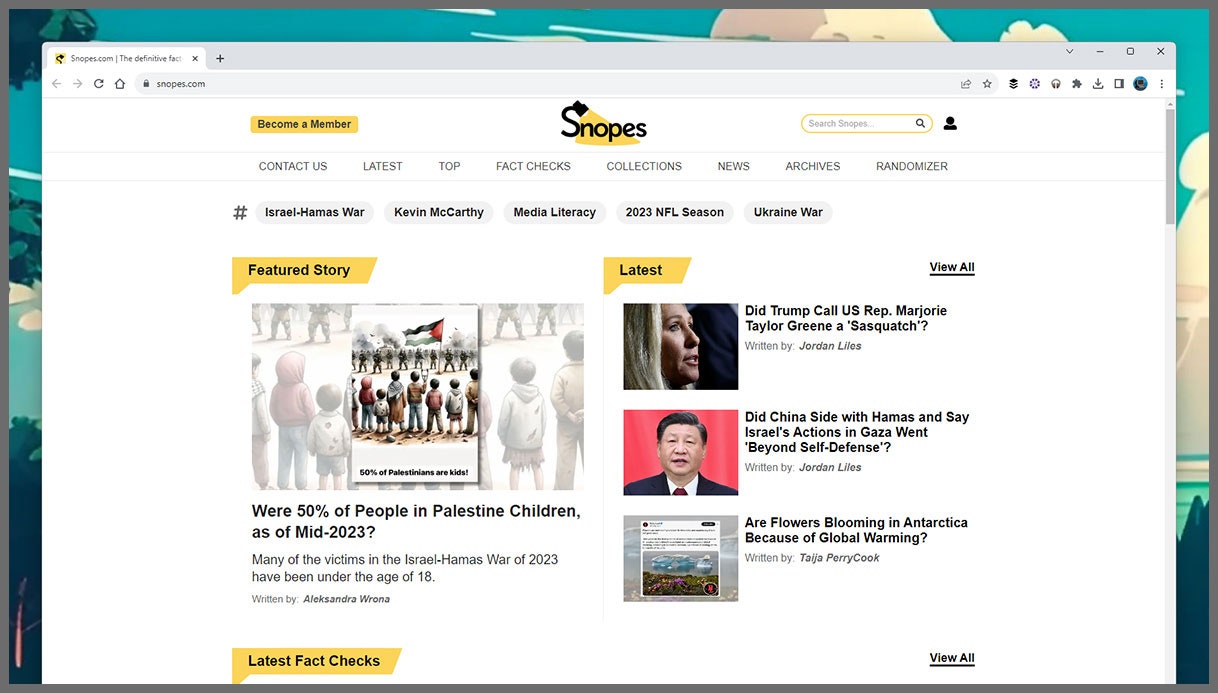

There are now several services dedicated to flagging misinformation and fake news reports. You may have heard of Snopes, which doesn’t just dispel urban myths, but also tackles contemporary news stories, complete with background and fact checks. Take, for example, this video that was incorrectly labeled as featuring a Palestinian flag, when it was in fact a Puerto Rican flag.

Courtesy of the Annenberg Public Policy Center comes FactCheck.org, which does exactly what its name suggests. It examines claims and counterclaims put forward by governments and other organizations and explains what’s true and not true about them. Here’s a story about an online video that misrepresented how Ukraine conscripted women into serving in the military, for instance.

There are other resources, including another fact-checking service from Reuters, that can be useful, especially when it comes to photos and video. There’s no guarantee that the content you’re unsure about is going to be covered by one of these sites, but it’s certainly worth checking.

Source : Wired