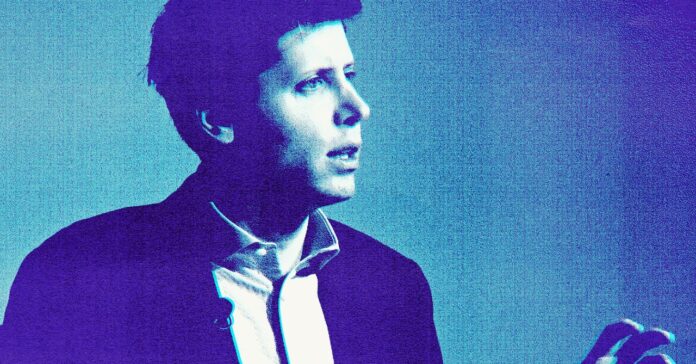

Sam Altman was reinstated soon after being fired as OpenAI CEO last month, but still stood to gain had the company continued to develop ChatGPT without him. During Altman’s tenure as CEO, OpenAI signed a letter of intent to spend $51 million on AI chips from a startup called Rain AI into which he has also invested personally.

Rain is based less than a mile from OpenAI’s headquarters in San Francisco and is working on a chip it calls a neuromorphic processing unit, or NPU, designed to replicate features of the human brain. OpenAI in 2019 signed a nonbinding agreement to spend $51 million on the chips when they became available, according to a copy of the deal and Rain disclosures to investors this year seen by WIRED. Rain told investors Altman had personally invested more than $1 million into the company. The letter of intent has not been previously reported.

The investor documents said that Rain could get its first hardware to customers as early as October next year. OpenAI and Rain declined to comment.

OpenAI’s letter of intent with Rain shows how Altman’s web of personal investments can entangle with his duties as OpenAI CEO. His prior position leading startup incubator Y Combinator helped Altman become one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent dealmakers, investing in dozens of startups and acting as a broker between entrepreneurs and the world’s biggest companies. But the distraction and intermingling of his myriad pursuits played some role in his recent firing by OpenAI’s board for uncandid communications, according to people involved in the situation but not authorized to discuss it.

The Rain deal also underscores OpenAI’s willingness to spend large sums to secure supplies of chips needed to underpin pioneering AI projects. Altman has complained publicly of a “brutal crunch” for AI chips and their “eye-watering” costs. OpenAI taps the powerful cloud of Microsoft, its primary investor, but has regularly shut off access to features of ChatGPT due to hardware constraints. According to a blog post about a closed door meeting he held with developers, Altman has said the pace of AI progress may be dependent on new chip designs and supply chains.

Rain touted its progress to potential investors earlier this year, projecting that as soon as this month it could “tape out” a test chip, a standard milestone in chip development referring to a design ready for fabrication. But the startup also has recently reshuffled its leadership and investors after reportedly an interagency US government body that polices investments for national security risks mandated Saudi Arabia-affiliated fund Prosperity7 Ventures to sell its stake in the company. The fund led a $25 million fundraise announced by Rain in early 2022.

The forced removal of the fund, first reported by Bloomberg Thursday and described in the documents seen by WIRED, could add to Rain’s challenges of bringing a novel chip technology to market, potentially delaying the day OpenAI can make good on its $51 million advance order. Silicon Valley-based Grep VC acquired the shares; it and the Saudi fund did not respond to requests for comment.

US concern about Prosperity7’s deal with Rain also raises questions about another effort by Altman to increase the world’s supply of AI chips. He’s talked to investors in the Middle East in recent months about raising money to start a new chip company to help OpenAI and others diversify beyond their current reliance on Nvidia GPUs and specialized chips from Google, Amazon, and a few smaller suppliers, according to two people seeking anonymity to discuss private talks.

Rain, founded in 2017, has claimed that its brain-inspired NPUs will yield potentially 100 times more computing power and, for training, 10,000 times greater energy efficiency than GPUs, the graphics chips that are the workhorses for AI developers such as OpenAI and primarily sourced from Nvidia.

Altman led one of Rain’s seed financings in 2018, the company has said, the year before OpenAI committed to spend $51 million on its chips. Rain now has about 40 employees, including experts in both development of AI algorithms and traditional chip design, according the disclosures.

The startup appears to have quietly changed its CEO this year and now lists founding CEO Gordon Wilson as executive advisor on its website, with former white-shoe law firm attorney William Passo gaining a promotion to CEO from COO.

Wilson confirmed his exit in a LinkedIn post Thursday, but did not provide a reason. “Rain is poised to build a product that will define new AI chip markets and massively disrupt existing ones,” he wrote. “Moving forward I will continue to help Rain in every way I can.” Over 400 LinkedIn users including some whose profiles say they are Rain employees commented on Wilson’s post or reacted to it with heart or thumbs up emojis—Passo wasn’t among them. Wilson declined to comment for this story.

The company will search for an industry veteran to permanently replace Wilson, according to an October note to investors seen by WIRED.

Rain’s initial chips are based on the RISC-V open-source architecture endorsed by Google, Qualcomm, and other tech companies and aimed at what the tech industry calls edge devices, located far from data centers, such as phones, drones, cars, and robots. Rain aims to provide a chip capable of both training machine algorithms and running them once they’re ready for deployment. Most edge chip designs today, like those found in smartphones, focus on the latter, known as inference. How OpenAI would use Rain chips could not be learned.

Rain at one point has claimed to investors that it has held advanced talks to sell systems to Google, Oracle, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon. Microsoft declined to comment, and the other companies did not respond to requests for comment.

The funding round led by Prosperity7 announced last year brought Rain’s total funding to $33 million as of April 2022. That was enough to operate through early 2025 and valued the company at $90 million excluding the new cash raised, according to the disclosures to investors. The documents cited Altman’s personal investment and Rain’s letter of intent with OpenAI as reasons to back the company.

In a Rain press release for the fundraise last year, Altman applauded the startup for taping out a prototype in 2021 and said it “could vastly reduce the costs of creating powerful AI models and will hopefully one day help to enable true artificial general intelligence.”

Prosperity7’s investment in Rain drew the interest of the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, which has the power to scuttle deals deemed to threaten national security.

CFIUS, as the committee is known, has long been concerned about China gaining access to advanced US semiconductors, and has grown increasingly worried about China using intermediaries in the Middle East to quietly learn more about critical technology, says Nevena Simidjiyska, a partner at the law firm Fox Rothschild who helps clients with CFIUS reviews. “The government doesn’t care about the money,” she says. “It cares about access and control and the power of the foreign party.”

Rain received a small seed investment from the venture unit of Chinese search engine Baidu apparently without problems but the larger Saudi investment attracted significant concerns. Prosperity7, a unit of Aramco Ventures, which is part of state-owned Saudi Aramco, possibly could have let the oil giant and other large companies in the Middle East to become customers but also put Rain into close contact with the Saudi government.

Megan Apper, a spokesperson for CFIUS, says the panel is “committed to taking all necessary actions within its authority to safeguard U.S. national security” but that “consistent with law and practice, CFIUS does not publicly comment on transactions that it may or may not be reviewing.”

Data disclosed by CFIUS shows it reviews hundreds of deals annually and in the few cases where it has concerns typically works out safeguards, such as barring a foreign investor from taking a board seat. It couldn’t be learned why the committee required full divestment from Rain.

Three attorneys who regularly work on sensitive deals say they could not recall any previous Saudi Arabian deals fully blocked by CFIUS. “Divestment itself has been quite rare over the past 20 years and has largely been a remedy reserved for Chinese investors,” says Luciano Racco, cochair of the international trade and national security practice at law firm Foley Hoag.

OpenAI likely needs to find partners with deep-pocketed backers if it is to gain some control over its hardware needs. Competitors Amazon and Google have spent years developing their own custom chips for AI projects and can fund them with revenue from their lucrative core businesses. Altman has refused to rule out OpenAI making its own chips, but that too would require significant funding.

Source : Wired