Do not preach doom to Yann LeCun. A pioneer of modern AI and Meta’s chief AI scientist, LeCun is one of the technology’s most vocal defenders. He scoffs at his peers’ dystopian scenarios of supercharged misinformation and even, eventually, human extinction. He’s known to fire off a vicious tweet (or whatever they’re called in the land of X) to call out the fearmongers. When his former collaborators Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio put their names at the top of a statement calling AI a “societal-scale risk,” LeCun stayed away. Instead, he signed an open letter to US president Joe Biden urging an embrace of open source AI and declaring that it “should not be under the control of a select few corporate entities.”

LeCun’s views matter. Along with Hinton and Bengio, he helped create the deep learning approach that’s been critical to leveling up AI—work for which the trio later earned the Turing Award, computing’s highest honor. Meta scored a major coup when the company (then Facebook) recruited him to be founding director of the Facebook AI Research lab (FAIR) in 2013. He’s also a professor at NYU. More recently, he helped persuade CEO Mark Zuckerberg to share some of Meta’s AI technology with the world: This summer, the company launched an open source large language model called Llama 2, which competes with LLMs from OpenAI, Microsoft, and Google—the “select few corporate entities” implied in the letter to Biden. Critics warn that this open source strategy might allow bad actors to make changes to the code and remove guardrails that minimize racist garbage and other toxic output from LLMs; LeCun, AI’s most prominent Pangloss, thinks humanity can deal with it.

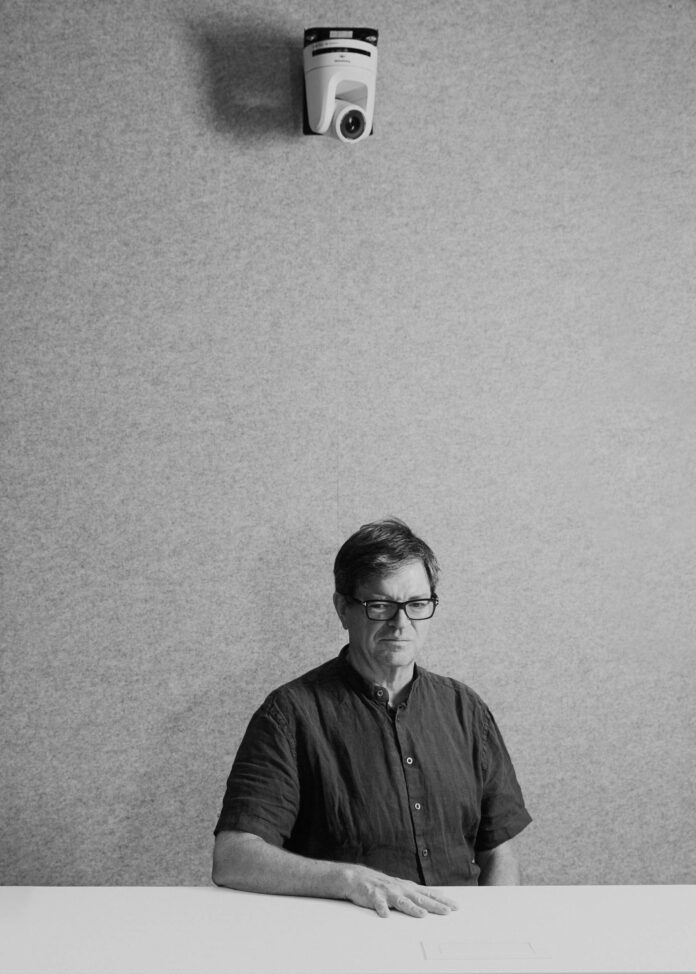

I sat down with LeCun in a conference room at Meta’s Midtown office in New York City this fall. We talked about open source, why he thinks AI danger is overhyped, and whether a computer could move the human heart the way a Charlie Parker sax solo can. (LeCun, who grew up just outside Paris, frequently haunts the jazz clubs of NYC.) We followed up with another conversation in December, while LeCun attended the influential annual NeurIPS conference in New Orleans—a conference where he is regarded as a god. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Steven Levy: In a recent talk, you said, “Machine learning sucks.” Why would an AI pioneer like you say that?

Yann LeCun: Machine learning is great. But the idea that somehow we’re going to just scale up the techniques that we have and get to human-level AI? No. We’re missing something big to get machines to learn efficiently, like humans and animals do. We don’t know what it is yet.

I don’t want to bash those systems or say they’re useless—I spent my career working on them. But we have to dampen the excitement some people have that we’re just going to scale this up and pretty soon we’re gonna get human intelligence. Absolutely not.

You act as though it’s your duty to call this stuff out.

Yeah. AI will bring a lot of benefits to the world. But people are exploiting the fear about the technology, and we’re running the risk of scaring people away from it. That’s a mistake we made with other technologies that revolutionized the world. Take the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. The Catholic Church hated it, right? People were going to be able to read the Bible themselves and not talk to the priest. Pretty much all the establishment was against the wide use of the printing press because it would change the power structure. They were right—it created 200 years of religious conflict. But it also brought about the Enlightenment. [Note: Historians might point out that the Church actually made use of the printing press for its own purposes, but whatever.]

Why are so many prominent people in tech sounding the alarm on AI?

Some people are seeking attention, other people are naive about what’s really going on today. They don’t realize that AI actually mitigates dangers like hate speech, misinformation, propagandist attempts to corrupt the electoral system. At Meta we’ve had enormous progress using AI for things like that. Five years ago, of all the hate speech that Facebook removed from the platform, about 20 to 25 percent was taken down preemptively by AI systems before anybody saw it. Last year, it was 95 percent.

How do you view chatbots? Are they powerful enough to displace human jobs?

They’re amazing. Big progress. They’re going to democratize creativity to some extent. They can produce very fluent text with very good style. But they’re boring, and what they come up with can be completely false.

The company you work for seems pretty hell bent on developing them and putting them into products.

There’s a long-term future in which absolutely all of our interactions with the digital world—and, to some extent, with each other—will be mediated by AI systems. We have to experiment with things that are not powerful enough to do this right now, but are on the way to that. Like chatbots that you can talk to on WhatsApp. Or that help you in your daily life and help you create stuff, whether it’s text or translation in real time, things like that. Or in the metaverse possibly.

How involved is Mark Zuckerberg in Meta’s AI push?

Mark is very much involved. I had a discussion with Mark early in the year and told him what I just told you, that there is a future in which all our interactions will be mediated by AI. ChatGPT showed us that AI could be useful for new products sooner than we anticipated. We saw that the public was much more captivated by the capabilities than we thought they would be. So Mark made the decision to create a product division focused on generative AI.

Why did Meta decide that Llama code would be shared with others, open source style?

When you have an open platform that a lot of people can contribute to, progress becomes faster. The systems you end up with are more secure and perform better. Imagine a future in which all of our interactions with the digital world are mediated by an AI system. You do not want that AI system to be controlled by a small number of companies on the West Coast of the US. Maybe the Americans won’t care, maybe the American government won’t care. But I tell you right now, in Europe, they won’t like it. They say, “OK, well, this speaks English correctly. But what about French? What about German? What about Hungarian? Or Dutch or whatever? What did you train it on? How does that reflect our culture?”

Seems like a good way to get startups to use your product and kneecap your competitors.

We don’t need to kneecap anyone. This is the way the world is going to go. AI has to be open source because we need a common infrastructure when a platform is becoming an essential part of the fabric of communication.

One company that disagrees with that is OpenAI, which you don’t seem to be a fan of.

When they started, they imagined creating a nonprofit to do AI research as a counterweight to bad guys like Google and Meta who were dominating the industry research. I said that’s just wrong. And in fact, I was proved correct. OpenAI is no longer open. Meta has always been open and still is. The second thing I said is that you’ll have a hard time developing substantial AI research unless you have a way to fund it. Eventually, they had to create a for-profit arm and get investment from Microsoft. So now they are basically your contract research house for Microsoft, though they have some independence. And then there was a third thing, which was their belief that AGI [artificial general intelligence] is just around the corner, and they were going to be the one developing it before anyone. They just won’t.

How do you view the drama at OpenAI, when Sam Altman was booted as CEO and then returned to report to a different board? Do you think it had an impact on the research community or the industry?

I think the research world doesn’t care too much about OpenAI anymore, because they’re not publishing and they’re not revealing what they’re doing. Some former colleagues and students of mine work at OpenAI; we felt bad for them because of the instabilities that took place there. Research really thrives on stability, and when you have dramatic events like this, it makes people hesitate. Also, the other aspect important for people in research is openness, and OpenAI really isn’t open anymore. So OpenAI has changed in the sense that they are not seen much as a contributor to the research community. That is in the hands of open platforms.

The shuffle at OpenAI has been called kind of a victory for AI “accelerationism,” which is the opposite of doomer-ism. I know you’re not a doomer, but are you an accelerationist?

No, I don’t like those labels. I don’t belong to any of those schools of thought or, in some cases, cults. I’m extremely careful not to push ideas of this type to the extreme, because you too easily get into purity cycles that lead you to do stupid things.

The EU recently issued a set of AI regulations, and one thing they did was largely exempt open source models. What will be the impact of that on Meta and others?

It affects Meta to some extent, but we have enough muscle to be compliant with whatever regulation is there. It’s much more important for countries that don’t have their own resources to build AI systems from scratch. They can rely on open source platforms to have AI systems that cater to their culture, their language, their interests. There’s going to be a future, probably not so far away, where the vast majority, if not all, of our interactions with the digital world will be mediated by AI systems. You don’t want those things to be under the control of a small number of companies in California.

Were you involved in helping the regulators reach that conclusion?

I was, but not directly with the regulators. I’ve been talking with various governments, particularly the French government, but indirectly to others as well. And basically, they got that message that you don’t want the digital diet of your citizens to be controlled by a small number of people. The French government bought that message pretty early on. Unfortunately, I didn’t speak to people at the EU level, who were more influenced by prophecies of doom and wanted to regulate everything to prevent what they thought were possible catastrophe scenarios. But that was blocked by the French, German, and Italian governments, who said you have to make a special provision for open source platforms.

But isn’t an open source AI really difficult to control—and to regulate?

No. For products where safety is really important, regulations already exist. Like if you’re going to use AI to design your new drug, there’s already regulation to make sure that this product is safe. I think that makes sense. The question that people are debating is whether it makes sense to regulate research and development of AI. And I don’t think it does.

Couldn’t someone take a sophisticated open source system that a big company releases, and use it to take over the world? With access to source codes and weights, terrorists or scammers can give AI systems destructive drives.

They would need access to 2,000 GPUs somewhere that nobody can detect, enough money to fund it, and enough talent to actually do the job.

Some countries have a lot of access to those kinds of resources.

Actually, not even China does, because there’s an embargo.

I think they could eventually figure out how to make their own AI chips.

That’s true. But it’d be some years behind the state of the art. It’s the history of the world: Whenever technology progresses, you can’t stop the bad guys from having access to it. Then it’s my good AI against your bad AI. The way to stay ahead is to progress faster. The way to progress faster is to open the research, so the larger community contributes to it.

How do you define AGI?

I don’t like the term AGI because there is no such thing as general intelligence. Intelligence is not a linear thing that you can measure. Different types of intelligent entities have different sets of skills.

Once we get computers to match human-level intelligence, they won’t stop there. With deep knowledge, machine-level mathematical abilities, and better algorithms, they’ll create superintelligence, right?

Yeah, there’s no question that machines will eventually be smarter than humans. We don’t know how long it’s going to take—it could be years, it could be centuries.

At that point, do we have to batten down the hatches?

No, no. We’ll all have AI assistants, and it will be like working with a staff of super smart people. They just won’t be people. Humans feel threatened by this, but I think we should feel excited. The thing that excites me the most is working with people who are smarter than me, because it amplifies your own abilities.

But if computers get superintelligent, why would they need us?

There is no reason to believe that just because AI systems are intelligent they will want to dominate us. People are mistaken when they imagine that AI systems will have the same motivations as humans. They just won’t. We’ll design them not to.

What if humans don’t build in those drives, and superintelligence systems wind up hurting humans by single-mindedly pursuing a goal? Like philosopher Nick Bostrom’s example of a system designed to make paper clips no matter what, and it takes over the world to make more of them.

You would be extremely stupid to build a system and not build any guardrails. That would be like building a car with a 1,000-horsepower engine and no brakes. Putting drives into AI systems is the only way to make them controllable and safe. I call this objective-driven AI. This is sort of a new architecture, and we don’t have any demonstration of it at the moment.

That’s what you’re working on now?

Yes. The idea is that the machine has objectives that it needs to satisfy, and it cannot produce anything that does not satisfy those objectives. Those objectives might include guardrails to prevent dangerous things or whatever. That’s how you make an AI system safe.

Do you think you’re going to live to regret the consequences of the AI you helped bring about?

If I thought that was the case, I would stop doing what I’m doing.

You’re a big jazz fan. Could anything generated by AI match the elite, euphoric creativity that so far only humans can produce? Can it produce work that has soul?

The answer is complicated. Yes, in the sense that AI systems eventually will produce music—or visual art, or whatever—with a technical quality similar to what humans can do, perhaps superior. But an AI system doesn’t have the essence of improvised music, which relies on communication of mood and emotion from a human. At least not yet. That’s why jazz music is to be listened to live.

You didn’t answer me whether that music would have soul.

You already have music that’s completely soulless. It’s played in restaurants as background music. They’re products, produced mostly by machines. And there is a market for that.

But I’m talking about the pinnacle of art. If I played you a recording that topped Charlie Parker at his best, and then told you an AI generated it, would you feel cheated?

Yes and no. So yes, because music is not just an auditory experience—a lot of it is cultural. It’s admiration for the performer. Your example would be like Milli Vanilli. Truthfulness is an essential part of the artistic experience.

If AI systems were good enough to match elite artistic achievements and you didn’t know the backstory, the market would be flooded with Charlie Parker–level music, and we wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

I don’t see any problem with that. I’d take the original for the same reason I would still buy a $300 handmade bowl that comes from a culture of hundreds of years, even though I can buy something that looks pretty much the same for 5 bucks. We still go to listen to my favorite jazz musicians live, even though they can be emulated. An AI system is not the same experience.

You recently received an honor from President Macron that I can’t pronounce …

Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur. It was created by Napoleon. It’s kind of like knighthood in the UK, except we had a revolution. So we don’t call people “Sir.”

Does that come with weaponry?

No, they don’t have swords and stuff like that. But people who have it can wear a little red stripe on their lapel.

Could an AI model ever win that award?

Not anytime soon. I don’t think it would be a good idea, anyway.

Source : Wired