Chinese Motifs in Art from Japan

20.03.2024 to 10.06.2024

Humboldt Forum

Ink and paper, silk and lacquer, bronze work and certain forms of wooden architecture, writing, belief practices such as those of Buddhism, some of the foundational structures of state organisation, and conceptions of art – all of these were introduced to Japan from China, often via Korea. These influences not only shaped the materials and techniques used; Chinese visual motifs and formal design elements also made their way across to the island kingdom, often adapted to suit local needs and transformed through novel combinations, additions, or refinements.

This temporary presentation, which draws from the collection of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, focuses on Chinese motifs in landscape and figure painting from 16th- to 19th-century Japan. A 16th-century painting that depicts returning sailboats in the night-time rain, for instance, is reminiscent of the “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers” landscape theme which was popularised in China in the 11th century. In adapted and altered form, these motifs can also be found in woodcuts, featured in scenes from the area surrounding Lake Biwa near Kyoto created by Utagawa Hiroshige around 1835.

The Shōki Myth

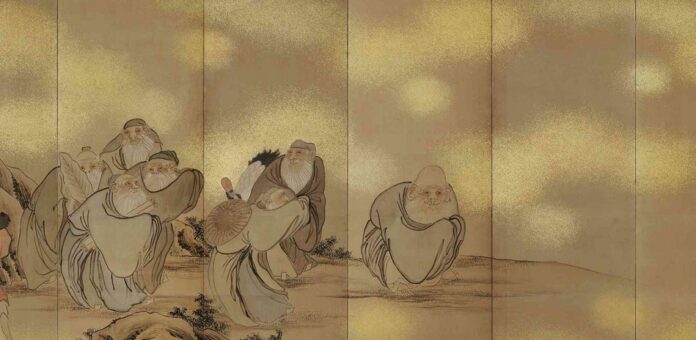

Legendary demon slayer Zhong Kui, who embodies a high regard for education and the ideal of the mandarin, re-appears in images from 18th- and 19th-century Japan as Shōki. Colour woodcuts and a book of block prints that feature both Zhong Kui (Shōki) and the legendary painter Wo Daozi (ca. 680–740) attest to the sustained popularity and prevalence of his myth in early 19th-century Japan. Daoist beliefs that immortality or magical abilities could be acquired by way of certain practices are embodied in groups of serene older men, or in the figure of Wang Qiao flying on a goose on a scroll painting by Katsushika Hokusai.

An Idealised China

In Japan, the figure of the mandarin (who in China qualified for their position by proving their abilities in a series of exams – at least in theory) was often connected with a yearning for a romanticised mainland culture where knowledge and education counted for more than one’s social background and wealth. Conceptions of an idealised China as a kingdom of immortals are present in allusions to the “Peach Blossom Spring” myth and in a style of landscape painting that often took stylistic cues from Chinese role models. These works display places of longing for Japanese painters and document forms of cultural transfer as well as appropriation and adaptation that were cultivated over centuries.

A temporary presentation by the Museum für Asiatische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin in the Humboldt Forum, Room 318, “Art from Japan”.

Source : Museen zu Berlin