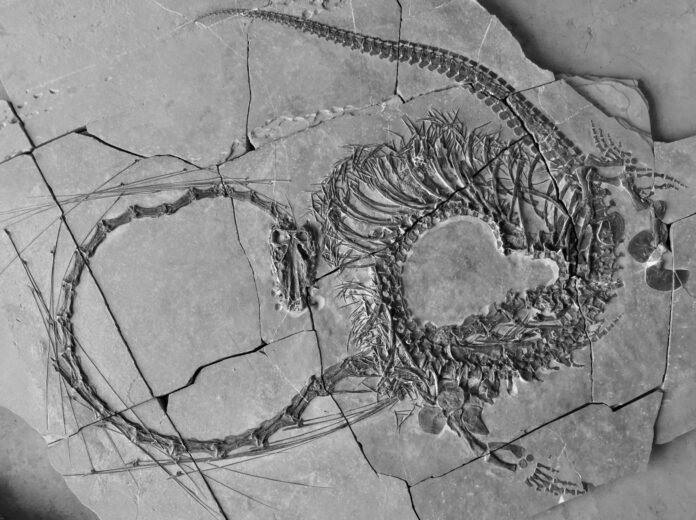

Earlier this year, a team of scientists made a splash when they revealed a remarkable new find — a complete skeleton of a 16-foot-long aquatic reptile, dubbed a “Chinese dragon” due to its serpentine appearance and exceptionally long neck. The species, Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, swam the seas during the Triassic period, and the fossil itself dates back 240 million years.

The fossil has fascinated — and baffled — scientists and the public alike. But previous fossil discoveries, as well as other specimens of the same creature, can help researchers arrive at a greater understanding of the strange-looking reptilian predator, which is difficult to compare to any modern-day species.

“They would have been up towards the top of the food chain, if not at the top of it,” says Nicholas Fraser, a paleontologist with National Museums Scotland and one of the scientists behind the recent find.

How Was the ‘Chinese Dragon’ Discovered?

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis was first described in 2003 by Fraser’s colleague Chun Li, a paleontologist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. That’s when Li saw a vertebrate fossil sitting in some rubble by the side of the road in Guizhou province in southern China. Li asked villagers in the region, who led him to a pigsty where he discovered further fossil remains.

Read More: 4 Dragons That Have Entered the Fossil Record

“It was a bit beaten up,” Fraser says, but Li eventually recovered most of the fossils in the neck right down to the hips.

At the time, the researchers didn’t have a complete specimen, though the creature already looked a little like another oddly-shaped Triassic reptile, Tanystropheus, first described in 1852. The latter also had a very long neck for a predator, with about 13 elongated neck vertebrae.

The new fossil has drawn comparisons to Tanystropheus, another strange, long-necked reptile that lived in the Triassic. (Credit: Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock)

“[Tanystropheus] has captured the imagination of paleontologists over the years,” Fraser adds.

What Did Dinocephalosaurus Look Like?

Still, Li continued to find additional fossils over the years, including a complete specimen, as described in a recent study detailing the discovery. In the process, Li and colleagues learned even more about Dinoocephalosaurus orientalis, and were able to describe it in its entirety for the first time.

For starters, the scientists saw that the reptile’s snake-like appearance was a result of the numerous vertebrae in its neck and torso. In contrast to Tanystropheus, with its 13 lengthy neck vertebrae, Dinocephalosaurus had at least 32. So while the two appear “equally bizarre” in some ways, and had about the same proportions, Dinocephalosaurus looks more like a snake or a Chinese dragon, Fraser says.

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis swimming alongside a school of prehistoric fish. (Credit: © Marlene Donelly)

The fossils also revealed that Dinocephalosaurus was roughly 20 feet long from head to tail. Nearly half of this was neck, which measured between 8 and 10 feet long. Its torso was only about 3 feet long, while its tail was another 6 feet or so.

Despite the large body, though, its head was tiny — only about 10 inches long. Much as in snakes, it’s similarly hard to differentiate the creature’s skull from its neck. Beyond that, its teeth are quite fearsome-looking, protruding from the side of the jaw and sticking out the sides, like those of a crocodile.

Read More: A Real-Life Dragon: How A Newly Classified Mosasaur Got Its Legendary Name

“It forms this sort of fish trap; once something goes in, it’s not coming out,” Fraser says, adding that the organism’s name, fittingly, translates to “terrible-headed reptile.”

In another contrast to Tanystropheus, which may have spent time on land, Dinocephalosaurus had four flippers for feet, and was likely fully aquatic. The deposits where it was found aren’t necessarily deep sea, adds Fraser, but still a ways offshore.

The Life of a ‘Chinese Dragon’

The researchers found fish remains in the stomach of one specimen, providing all we know about its diet. It’s unclear whether this was typical prey, or just an odd last meal for the individual, but Fraser says it’s safe to say that fish likely formed part of its diet.

Interestingly, the bizarre shape of these fossils makes it difficult to determine how Dinocephalosaurus survived, and what its hunting strategy may have been. “We have no modern analogue,” Fraser says.

Read More: Why Were Prehistoric Marine Reptiles So Huge?

In part, that ambiguity is because Dinocephalosaurus is fully aquatic, making it less clear how it used its odd shape to navigate the world. Perhaps it used its long, small neck to get into crevices, or maybe it exploited a murky underwater environment where it could better ambush smaller fish.

“[Perhaps] none of the fishes are afraid of what appears to be a small animal,” Fraser says, “because they can’t see the rest of it in the murky depths.”

These creatures weren’t the largest predators around at the time, but they still weren’t small by any means. Even with their impressive length, Fraser says that the larger ichthyosaurs of the era — massive marine reptiles that once ruled the seas — may have preyed on Dinocephalosaurus.

How Did Dinocephalosaurus Reproduce?

The researchers had yet another surprise when analyzing the Dinocephalosaurus fossils: a baby was inside the body of one of the larger specimens.

In this case, it’s possible that the creature had just cannibalized a younger Dinocephalosaurus, as crocodilians are known to do. But Fraser believes it may be an embryo. Laying eggs on land like sea turtles may have been difficult given its awkward shape and size, he says, so these creatures may not have lain eggs at all.

Read More: Are Dragons Real? The Unique History and Origins of Mythical Dragons

In other words, the smaller Dinocephalosaurus inside the larger fossil was potentially its developing offspring. “I think this is probably good evidence that [the reptile was capable of] giving birth to live young,” Fraser says.

Source : Discovermagazine