I’m fond of effective altruists. When you meet one, ask them how many people they’ve killed.

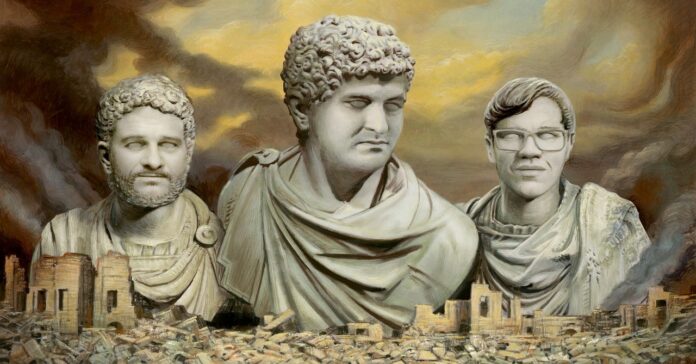

Effective altruism is the philosophy of Sam Bankman-Fried, the crypto wunderkind due to be sentenced tomorrow for fraud and money laundering. Elon Musk has said that EA is close to what he believes. Facebook mogul Dustin Moskovitz and Skype cofounder Jaan Tallinn have spent mega-millions on its causes, and EAs have made major moves to influence American politics. In 2021, EA boasted of $46 billion in funding—comparable to what it’s estimated the Saudis spent over decades to spread Islamic fundamentalism around the world.

Effective altruism pitches itself as a hyperrational method of using any resource for the maximum good of the world. Here in Silicon Valley, EA has become a secular religion of the elites. Effective altruists filled the board of OpenAI, the $80 billion tech company that invented ChatGPT (until the day in November when they nearly crashed the company). EA is also heavily recruiting young people across rich universities like Stanford, where I work. Money is flowing from EA headquarters to entice students at Yale, Columbia, Berkeley, Penn, Swarthmore—if you went to a wealthy school, you’ll find EAs all over your alma mater.

Before the fall of SBF, the philosophers who founded EA glowed in his glory. Then SBF’s crypto empire crumbled, and his EA employees turned witness against him. The philosopher-founders of EA scrambled to frame Bankman-Fried as a sinner who strayed from their faith.

Yet Sam Bankman-Fried is the perfect prophet of EA, the epitome of its moral bankruptcy. The EA saga is not just a modern fable of corruption by money and fame, told in exaflops of computing power. This is a stranger story of how some small-time philosophers captured some big-bet billionaires, who in turn captured the philosophers—and how the two groups spun themselves into an opulent vortex that has sucked up thousands of bright minds worldwide.

The real difference between the philosophers and SBF is that SBF is now facing accountability, which is what EA’s founders have always struggled to escape.

If you’ve ever come across effective altruists, you’re likely fond of them too. They tend to be earnest young people who talk a lot about improving the world. You might have been such a young person once—I confess that I was. A decade before the founding of effective altruism, I too set out to save the world’s poorest people.

I grew up like today’s typical EA. White, male, a childhood full of Vulcans and Tolkien, Fortran and Iron Man. I went into philosophy because it felt like a game, a game played with ideas. In 1998, with a freshly minted Harvard PhD, I was playing with the ideas of Peter Singer, today’s most influential living philosopher.

The idea of Singer that excited me was that each of us should give a lot of money to help poor people abroad. His “shallow pond” thought experiment shows why. If you saw a child drowning in a shallow pond, you’d feel obliged to rescue her even if that meant ruining your new shoes. But then, Singer said, you can save the life of a starving child overseas by donating to charity what new shoes would cost. And you can save the life of another child by donating instead of buying a new shirt, and another instead of dining out. The logic of your beliefs requires you to send nearly all your money overseas, where it will go farthest to save the most lives. After all, what could we do with our money that’s more important than saving people’s lives?

That’s the most famous argument in modern philosophy. It goes well beyond the ideas that lead most decent people to give to charity—that all human lives are valuable, that severe poverty is terrible, and that the better-off have a responsibility to help. The relentless logic of Singer’s “shallow pond” ratchets toward extreme sacrifice. It has inspired some to give almost all their money and even a kidney away.

In 1998, I wasn’t ready for extreme sacrifice; but at least, I thought, I could find the charities that save the most lives. I started to build a website (now beyond parody) that would showcase the evidence on the best ways to give—that would show altruists, you might say, how to be most effective. And then I went to Indonesia.

A friend who worked for the World Wildlife Fund had invited me to a party to mark the millennium, so I saved up my starting-professor’s salary and flew off to Bali. My friend’s bungalow, it turned out, was a crash pad for young people working on aid projects across Indonesia and Malaysia, escaping to Bali to get some New Year’s R&R.

These young aid workers were with Oxfam, Save the Children, some UN organizations. And they were all exhausted. One nut-tan young Dutch fellow told me he slept above the pigs on a remote island and had gotten malaria so many times he’d stop testing. Two weary Brits told of confronting the local toughs they always caught stealing their gear. They all scrubbed up, drank many beers, rested a few days. When we decided to cook a big dinner together, I grabbed my chance for some research.

“Say you had a million dollars,” I asked when they’d started eating. “Which charity would you give it to?” They looked at me.

“No, really,” I said, “which charity saves the most lives?”

“None of them,” said a young Australian woman to laughter. Out came story after story of the daily frustrations of their jobs. Corrupt local officials, clueless charity bosses, the daily grind of cajoling poor people to try something new without pissing them off. By the time we got to dessert, these good people, devoting their young lives to poverty relief, were talking about lying in bed forlorn some nights, hoping their projects were doing more good than harm.

That was a shock. And, I’m embarrassed to say, a deeper shock came when I left Bali’s beaches to drive to the poorer parts of the island. That shock was the simple revelation of the reality of the people there. The Balinese I met seemed at least as upright and resourceful as the folks I knew back home; their daily lives were certainly more challenging. Glimpsing the world through the eyes of these villagers, and the immense distance between us, crashed through the games in my mind.

You might think it pitiful, even offensive, that it took some luxury tourism to give me a sense of the reality of severe poverty. Let me ask your mercy. I thought my little website could help save lives—and saving lives is what firemen do. Saving lives is what Spider-Man does. I thought I could save lives by being clever: the philosopher’s way of being the hero. I left the island so ashamed.

I still wanted to help. But I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I canned the website and spent a decade learning about poverty and aid.

Aid organizations, I learned, have been through many cycles of enthusiasm since the 1960s. Every few years, an announcement—“We’ve finally found the thing that works to end poverty”—would be followed by disillusionment. (In the early 2000s, the “thing” was microfinance.) Experts who studied aid had long been at loggerheads, with Nobel laureates pitted against one another. Boosters wrote books like The End of Poverty: How We Can Make It Happen in Our Lifetime. Skeptics wrote books like The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good.

Hundreds of millions of people were living each day on less than what $2 can buy in America. Fifty thousand people were dying every day from things like malaria and malnutrition. Each of those lives was as important as mine. Why was it so hard to figure out what can help—to find out what works to reduce extreme poverty?

While I was learning about aid, real progress was made on the “What works?” question. People started testing aid projects like drugs. Give half of the villages bed nets, make the other villages the “control group,” and you can get a better idea of what benefits the bed nets are bringing. Experts still debate how much weight to give these results. But the drug trial innovation in aid was encouraging.

Still, even “control group” testing, I learned, gives only a close-up view of what’s happening. Extremely poor people live in complex environments—just as complex as our own, and usually more chaotic. Sending in extra resources can have all sorts of effects beyond what a close-up shows. And that’s the real problem in finding “what works.”

Say I give some money to a charity that promises to better the health of poor people in Africa or Asia. And let’s say that, in a close-up view, it works. What else might my money have done? Lots of things. Maybe bringing in the charity will boost the power of a local potentate. Maybe the charity’s donated medicines will just free up money in the budget of an oppressive regime. Maybe the project will weaken the social contract between the people and their government—after all, why would the state care for the health of its citizens, and why would citizens even demand health care from the state, if rich foreigners are paying for it?

Aid experts know all about these negative impacts, plus many others—they’re like the side effects of drugs. A blood-thinning drug may lower the risk of stroke, but it can also keep wounds from healing. Taking lots of painkillers might damage your kidneys.

One way to get a sense of the side effects of aid is to try to imagine that you and I someday become the targets of an aid project. Imagine that over the next 20 years, China’s economy rockets upward while our country suffers cascading failures and sinks deep into poverty and dysfunction. Now imagine a future where some Chinese trillionaires decide to help out children in our country. Chinese researchers have invented a pill that adds a month of life expectancy to every child who takes it. The trillionaires send the pills to the school superintendent in our town, and the superintendent orders the teachers to distribute the pills before class.

You piece all this together the day your two kids call you to pick them up at school. One child is vomiting, the other is too faint to walk home. The teachers gave your kids the pills this morning without asking you. By the next day your kids are feeling better—but how do you feel? How do you feel about the teachers and the superintendent? What do you think about those Chinese trillionaires, now bragging back home about how they’ve helped the poor foreigners?

It took me, a philosopher, years to learn what might be obvious to you. The “close-up” effects of pills or bed nets are easy to advertise, but the side effects—political, economic, psychological—are just as important. Most important, of course, will be what the local people think about interventions into their lives. Yet their very poverty means they can’t hold anyone accountable for harms they suffer.

I drafted an article on what I’d learned about aid and called it “Poverty Is No Pond.” Making responsible choices, I came to realize, means accepting well-known risks of harm. Which absolutely does not mean that “aid doesn’t work.” There are many good people in aid working hard on the ground, often making tough calls as they weigh benefits and costs. Giving money to aid can be admirable too—doctors, after all, still prescribe drugs with known side effects. Yet what no one in aid should say, I came to think, is that all they’re doing is improving poor people’s lives.

Just as I was finishing my work on aid, a young philosopher from Oxford gave a lecture at my university, saying that all he was doing was improving poor people’s lives. This was Toby Ord, who was just then starting effective altruism.

Like me a dozen years earlier, Ord was excited by Peter Singer’s “shallow pond” argument. What he added to it, he said, was a way of measuring how many people’s lives he could save. The simple version goes like this. Say there’s a pill that adds a year of life to anyone who takes it. If Ord gives $50 to an aid charity, it will give out 50 pills to poor foreigners. So with his donation, he has added a total of 50 years of life. And adding 50 years is like saving the life of one child drowning in a pond. So by giving $50, he has “saved the life” of one poor child.

Onstage with Ord that day was a former director of Christian Aid who’d written a massive book called Does Foreign Aid Really Work? This expert tried to persuade Ord that aid was much more complex than “pills improve lives.” Over dinner I pressed Ord on these points—in fact I harangued him, out of frustration and from the shame I felt at my younger self. Early on in the conversation, he developed what I’ve come to think of as “the EA glaze.”

It’s difficult to get a man to understand something, said Upton Sinclair, when his salary depends on his not understanding it. And all the more when his self-image does. Ord, it seemed, wanted to be the hero—the hero by being smart—just as I had. Behind his glazed eyes, the hero is thinking, “They’re trying to stop me.”

Not long before then, two hedge-fund analysts in their twenties quit their jobs to create an “effective giving” website, with an aim similar to the website I’d abandoned years earlier. They called it GiveWell. Like me in 1998, the two had no background in aid. But they’d found a charity that gave out bed nets in Madagascar. They checked how much it cost to give out bed nets and how likely bed nets are to prevent malaria. They used a method like Ord’s for measuring “lives saved” per dollar spent, with calculations that unfurled in a 17-row table of precise, decimal-pointed numbers. They put on their website that this charity could save a life for $820.

I added a bit about GiveWell to “Poverty Is No Pond,” asking about the possible side effects of its bed net charity. For instance, had its charity been taxed to support Madagascar’s corrupt president? Had their charity weakened the social contract by supplanting Madagascar’s health service, which had been providing bed nets for its own citizens?

I sent my draft to GiveWell. Its then co-director, Holden Karnofsky, replied he was confident that well-run charities, like the one that gave out bed nets, were beneficial overall—that the benefits to poor people minus the harms to poor people (maybe not the same poor people) was a positive number. I asked whether they’d be willing to mention possible harms on their website every time they asked for money. Karnofsky said it made sense to highlight harms, and they’d make a better effort to make the website clear about what went into their calculations.

That was more than a dozen years ago. Today, GiveWell highlights detailed calculations of the benefits of donations to recipients. In an estimate from 2020, for example, it calculates that a $4,500 donation to a bed nets charity in Guinea will pay for the delivery of 1,001 nets, that 79 percent of them will get used, that each net will cover 1.8 people, and so on. Factoring in a bevy of such statistical likelihoods, GiveWell now finds that $4,500 will save one person.

That looks great. Yet GiveWell still does not tell visitors about the well-known harms of aid beyond its recipients. Take the bed net charity that GiveWell has recommended for a decade. Insecticide-treated bed nets can prevent malaria, but they’re also great for catching fish. In 2016, The New York Times reported that overfishing with the nets was threatening fragile food supplies across Africa. A GiveWell blog post responded by calling the story’s evidence anecdotal and “limited,” saying its concerns “largely don’t apply” to the bed nets bought by its charity. Yet today even GiveWell’s own estimates show that almost a third of nets are not hanging over a bed when monitors first return to check on them, and GiveWell has said nothing even as more and more scientific studies have been published on the possible harms of bed nets used for fishing. These harms appear nowhere in GiveWell’s calculations on the impacts of the charity.

In fact, even when GiveWell reports harmful side effects, it downplays and elides them. One of its current top charities sends money into dangerous regions of Northern Nigeria, to pay mothers to have their children vaccinated. In a subsection of GiveWell’s analysis of the charity, you’ll find reports of armed men attacking locations where the vaccination money is kept—including one report of a bandit who killed two people and kidnapped two children while looking for the charity’s money. You might think that GiveWell would immediately insist on independent investigations into how often those kinds of incidents happen. Yet even the deaths it already knows about appear nowhere in its calculations on the effects of the charity.

And more broadly, GiveWell still doesn’t factor in many well-known negative effects of aid. Studies find that when charities hire health workers away from their government jobs, this can increase infant mortality; that aid coming into a poor country can increase deadly attacks by armed insurgents; and much more. GiveWell might try to plead that these negative effects are hard to calculate. Yet when it calculates benefits, it is willing to put numbers on all sorts of hard-to-know things.

It looks very much like GiveWell is trying to skirt its reputation for unsentimental, computerlike calculation. If probabilities of benefits add up by fractions, then probabilities of harms must rack up too. In a comment to WIRED, GiveWell CEO Elie Hassenfeld said the organization “does tens of thousands of hours of research every year” so that “donors who want to do as much good as possible can make informed decisions on where to give.” But those donors could be far better informed. Think of a drug company that’s unwilling to report any data on harmful side effects, and when pressed merely expresses confidence that its products are “overall beneficial.” GiveWell is like that—except that the benefits it reports may go to some poor people, while the harms it omits may fall on others. Today GiveWell’s front page advertises only the number of lives it thinks it has saved. A more honest front page would also display the number of deaths it believes it has caused.

I finished up “Poverty Is No Pond” and added one more point, which I’ve come to think is the most important to make to EAs: Extreme poverty is not about me, and it’s not about you. It’s about people facing daily challenges that most of us can hardly imagine. If we decide to intervene in poor people’s lives, we should do so responsibly—ideally by shifting our power to them and being accountable for our actions.

After that, I figured that EA would come to grief, and I moved on to other work. What I didn’t see coming was the pitchman and the billionaires.

The pitchman was Will MacAskill, another young Oxford EA with a PhD in philosophy. In 2012, MacAskill had been trawling elite American universities, looking to catch future EA funders. At MIT he met an undergraduate physics major with an interest in animal welfare, Sam Bankman-Fried. MacAskill told SBF that the most good he could do was actually to go into finance, get filthy rich, and give big money to the cause. “Earning to give,” he called it. It was the perfect net to catch that particular fish.

Where Ord was earnest, MacAskill was shameless. “HOW YOU CAN SAVE HUNDREDS OF LIVES” is the name of a chapter in his pitch book for EA. The book tells you that you can be a hero by giving to charities in the EA way—you’ll be like the guy who pulls people from a burning building, it says, or even like Oskar Schindler. Your heroic donations can do “a tremendous amount of good.”

MacAskill admits that many experts are skeptics about aid. Yet he gushes that aid has been “incredibly beneficial”:

Now this is pure hooey. Even aid’s biggest boosters would cringe at the implication that aid had caused a 50 percent increase in sub-Saharan life expectancies. And what follows this astonishing statement is a tangle of qualifications and irrelevancies trailing off into the footnotes. To anyone who knows even a little about aid, it’s like MacAskill has tattooed “Not Serious” on his forehead.

He then makes his pitch for specific interventions in poor countries. He pours scorn on the last “thing” in aid that was going to solve everything—microcredit. He then pushes the latest thing, which at that time was giving deworming pills to poor children. You can guess what happened after his book was published. The same research organization that MacAskill singled out for its rigorous evaluations released a report finding no proof of benefits from mass deworming. GiveWell, which had given a deworming charity its top rating for almost a decade, down-rated it and now no longer accepts donations for it.

In making his pitch to donors, MacAskill left out many of the possible impacts of the charities that “save lives”—he made the drug commercial without the part about all the side effects. Remember the imaginary story about the Chinese trillionaires and kids getting sick from pills their parents never consented to? That story was based on what actually happened in Tanzania when a mass deworming initiative—a kind of aid MacAskill promoted—was rolled out. Some angry parents rioted when they discovered what had been done to their children.

For a philosopher to talk applesauce about aid is not so surprising. For a philosopher to peddle bad philosophy is something else.

Let me give a sense of how bad MacAskill’s philosophizing is. Words are the tools of the trade for philosophers, and we’re pretty obsessive about defining them. So you might think that the philosopher of effective altruism could tell us what “altruism” is. MacAskill says,

No competent philosopher could have written that sentence. Their flesh would have melted off and the bones dissolved before their fingers hit the keyboard. What “altruism” really means, of course, is acting on a selfless concern for the well-being of others—the why and the how are part of the concept. But for MacAskill, a totally selfish person could be an “altruist” if they improve others’ lives without meaning to. Even Sweeney Todd could be an altruist by MacAskill’s definition, as he improves the lives of the many Londoners who love his meat pies, made from the Londoners he’s killed.

And then there’s MacAskill’s philosophy of how to give credit, which is a big part of how he persuades people to give to EA charities. The measure of what you achieve, MacAskill writes, is the difference you make in the world: “the difference between what happens as a result of your actions and what would have happened anyway.” If you donate enough money to a charity that gives out insecticide-treated bed nets, MacAskill says, you will “save the life” of someone who otherwise would have died of malaria—just as surely as if you ran into a burning building and dragged a young child to safety.

But let’s picture that person you’ve supposedly rescued from death in MacAskill’s account—say it’s a young Malawian boy. Do you really deserve all the credit for “saving his life”? Didn’t the people who first developed the bed nets also “make a difference” in preventing his malaria? More importantly, what about his mother? She chose to trust the aid workers and use the net they handed to her, which not all parents do. Doesn’t her agency matter—doesn’t her choice to use the net “make a difference” in what happens to her child? Wouldn’t it in fact be more accurate for MacAskill to say that your donation offers this mother the opportunity to “save the life” of her own child?

Success has many parents, as the old saw says, while failure is an orphan. But all right, let’s say that MacAskill is right and each person is responsible for everything that wouldn’t have happened without what they did. Then it would follow that each person is responsible for the bad as well as the good. We know that MacAskill persuaded Sam Bankman-Fried to go into finance instead of into animal welfare. By his own theory, MacAskill would then be responsible for what SBF did in finance. So MacAskill should be demanding to go to prison along with SBF, right?

None of this tomfoolery would matter if it weren’t for the tech billionaires. The EAs spoke in a language that came naturally to them.

The core of EA’s philosophy is a mental tool that venture capitalists use every day. The tool is “expected value” thinking, which you may remember from Economics 101. Say you’re trying to maximize returns on $100. You guess that some stock has a 60 percent chance of gaining $10 and a 40 percent chance of losing $10. Multiplying through, you find that this stock has an expected value of $102. You then repeat these calculations for the other stocks you could buy. The most rational gamble is to buy the stock with the highest expected value.

Expected value thinking can be applied to any choice, and it needn’t be selfish. You can aim at the most value-for-you, or the most value-for-the-universe—the method is the same. What EA pushes is expected value as a life hack for morality. Want to make the world better? GiveWell has done the calculations on how to rescue poor humans. A few clicks and you’re done: Move fast and save people. EA even set up a guidance counseling service that championed the earning-to-give strategy. EA showed math-talented students that getting really rich in finance would let them donate lots of money to EA. A huge income for yourself can SAVE HUNDREDS OF LIVES.

Expected value thinking can be useful in finance. But what if someone actually hacked their whole life with it? What if someone tried to calculate the expected value of every choice they made, every minute of every day?

That’s Sam Bankman-Fried. SBF was easy for EA to recruit because its life hack was already his mindset. As Michael Lewis writes, with every choice SBF thinks in terms of maximizing expected value. And his calculations are “rational” in being free from emotional connections to other people. EA encourages people to be more “rational” like this. SBF is a natural.

To get yourself into SBF’s mindset, consider whether you would play the following godlike game for real. In this game, there’s a 51 percent chance that you create another Earth but also a 49 percent chance that you destroy all human life. If you’re using expected value thinking, and if you think that human life has positive value, you must play this game. SBF said he would play this game. And he said he would keep playing it, double or nothing, over and over again. With expected value thinking, the slightly higher chance of creating more value requires endlessly risking the annihilation of humanity.

Expected value is why SBF constantly played video games, even while Zooming with investors. He calculated that he could add the pleasure of the game to the value of the calls. The key to understanding SBF is that he plays people like they’re games too. With his long-suffering EA girlfriend, her expected value went up when he wanted sex and then down right afterward (again according to Lewis). This is the perfection of the EA philosophy: Maximize the value of the use of any given resource. And aren’t other people resources that can produce value?

After all the media, the biographies, the trial, and the sentencing, people have different reads on Sam Bankman-Fried. Is he a selfish villain or an unlucky saint? Was he really aiming at maximum value-for the-universe? Or maximum value-for-Sam?

I suspect that, in his mind, the two aims converged. If you’re earning-to-give, you should maximize your wealth. And if you think each moment should be optimized for profit, you’ll never choose to spend resources on boring grown-up things like auditors and a chief financial officer. For SBF, good-for-me-now and good-for-everyone-always started to merge into one.

And yet, as we know, SBF consistently made terrible choices, even beyond the way he ran his company. During his detention, prosecutors allege, he made the disastrous decision to leak his girlfriend’s diaries to the press. The judge, who anyone could see was not playing, threw him in jail. At the trial, he insisted on testifying and was predictably abysmal on the stand. His calculations seemed cockeyed throughout.

Here we need to jump from Econ to Psych 101. As Daniel Kahneman says, “We think, each of us, that we’re much more rational than we are.” When doing expected value thinking, the potential for rationalization and self-serving bias are immense. In the trial, SBF’s self-deceptions finally hit reality. The jury found him obviously guilty of seven counts of fraud and conspiracy. He’s now facing accountability for what can only be called his irrationality. The actual value of all his expected value calculations turned out to be a penalty assigned by a judge.

When SBF’s frauds were first revealed, the EA philosophers tried mightily to put as much distance as they could between themselves and him. Yet young EAs should think carefully about how much their leaders’ reasoning shared the flaws of Sam Bankman-Fried’s.

With the philosophers too, good-for-others kept merging into good-for-me. SBF bought his team extravagant condos in the Bahamas; the EAs bought their crew a medieval English manor as well as a Czech castle. The EAs flew private and ate $500-a-head dinners, and MacAskill’s second book had a lavish promotion campaign that got him the cover story of Time magazine. For philosophers who thought themselves bringing such extraordinary goodness to the world, these personal benefits must have seemed easy to justify. Philosophy gives no immunity against self-deceit.

While SBF’s money was still coming in, EA greatly expanded its recruitment of college students. GiveWell’s Karnofsky moved to an EA philanthropy that gives out hundreds of millions of dollars a year and staffed up institutes with portentous names like Global Priorities and The Future of Humanity. Effective altruism started to synergize with adjacent subcultures, like the transhumanists (wannabe cyborgs) and the rationalists (think “Mensa with orgies”). EAs filled the board of one of the Big Tech companies (the one they later almost crashed). Suddenly, EA was everywhere. It was a thing.

This was also a paradoxical time for EA’s leadership. While their following was growing ever larger, their thinking was looking even soggier.

You can see this by what GiveWell became. During the flush times, the pitch pages of its website juiced donors by advertising its “in-depth evaluations” of “highly effective charities” which do “an incredible amount of good.” The pitch came with precise figures: the cost to “save a life” (now up to $3,500) and the total lives GiveWell has “saved” (now up to 75,000). But in the sub-subpages, it turned out that these precise figures were based on very weak evidence and endless hedging.

For example, remember that deworming charity that was one of GiveWell’s top recommendations for almost a decade (until, in 2022, it wasn’t)? GiveWell’s “in-depth research” found it “highly effective.” Yet what was GiveWell’s “strongest piece of evidence” that the charity improved on what local governments were doing anyway? In the fine print, that piece of evidence turns out to be a single interview with a low-level official in one of the five countries where the charity worked—that’s it.

Then there’s the hedging. GiveWell’s pitch page projects absolute confidence in its exact numbers; the nested links tell a different story. In the fine print, the calculations are hedged with phrases like “very rough guess,” “very limited data,” “we don’t feel confident,” “we are highly uncertain,” “subjective and uncertain inputs.” These pages also say that “we consider our cost-effectiveness numbers to be extremely rough,” and that these numbers “should not be taken literally.” What’s going on?

MacAskill’s second book was also what the Brits call fur-coat-and-no-knickers and was even more shameless than his first. (The first book tells you where to give your money; the second tells you how to run most of your life.) Up front, MacAskill says that he has “relied heavily on an extensive team of consultants and research assistants” and that the book represents more than a decade of full-time work, including almost two years of fact-checking.

This bravado carries over into the blunt advice that MacAskill gives throughout the book. For instance, are you concerned about the environment? Recycling or changing your diet should not be your priority, he says; you can be “radically more impactful.” By giving $3,000 to a lobbying group called Clean Air Task Force (CATF), MacAskill declares, you can reduce carbon emissions by a massive 3,000 metric tons per year. That sounds great.

Friends, here’s where those numbers come from. MacAskill cites one of Ord’s research assistants—a recent PhD with no obvious experience in climate, energy, or policy—who wrote a report on climate charities. The assistant chose the controversial “carbon capture and storage” technology as his top climate intervention and found that CATF had lobbied for it. The research assistant asked folks at CATF, some of their funders, and some unnamed sources how successful they thought CATF’s best lobbying campaigns had been. He combined these interviews with lots of “best guesses” and “back of the envelope” calculations, using a method he was “not completely confident” in, to come up with dollar figures for emissions reductions. That’s it.

Strong hyping of precise numbers based on weak evidence and lots of hedging and fudging. EAs appoint themselves experts on everything based on a sophomore’s understanding of rationality and the world. And the way they test their reasoning—debating other EAs via blog posts and chatboards—often makes it worse. Here, the basic laws of sociology kick in. With so little feedback from outside, the views that prevail in-group are typically the views that are stated the most confidently by the EA with higher status. EAs rediscovered groupthink.

At some point, the money took over. The philosophers invited the tech billionaires to dance. Then the billionaires started calling the tunes.

I suspect that the tech billionaires didn’t want to be heroes merely by saving individual lives. That’s just what firemen do; that’s just what Spider-Man does. The billionaires wanted to be heroes who saved the whole human race. That’s what Iron Man does. SBF was never really interested in bed nets. His all-in commitment was to a philosophy of creating maximum value for the universe, until it ends.

So that became the philosophers’ goal too. They started to emphasize a philosophy, longtermism, that holds the moral worth of unborn generations equal to the worth of living ones. And actually, unborn generations could be worth a lot more than we are today, given population growth. What’s the point in deworming a few hundred kids in Tanzania when you could pour that money into astronautical research instead and help millions of unborn souls to escape Earth and live joyfully among the stars?

Conveniently for both the billionaires and the philosophers, longtermism removed any risk of being proved wrong. No more annoyances like bad press for the charities you’ve recommended. Now they could brag that they were guarding the galaxy, with no fear of any back talk from the people of the 22nd century.

Some smart young EAs dared to object publicly to longtermism’s primitive and dangerous reasoning. Senior figures in the movement tried to suppress their criticisms, saying that any critiques of central EA figures might threaten future funding. This final phase of EA is where things got genuinely odd.

What’s good in longtermism isn’t new, and what’s new isn’t good. Sages from Gautama Buddha to Jeremy Bentham have encouraged us to aim at the welfare of all sentient creatures. What the longtermists add is the party trick of assigning probabilities to everything. Ord, in his longtermist book, puts the odds of humanity suffering an existential catastrophe in this century at just under 17 percent.

What MacAskill adds is, again, an amusing lack of humility. His own longtermist book sees him expounding on how we must “structure global society” and “safeguard civilization.” On averting nuclear war, fighting deadly pathogens, and choosing the values to guide humanity’s future, MacAskill claims to know what the world must do.

In other words, we’re still in the land of precise guesses built on weak evidence, but now the stakes are higher and the numbers are distant probabilities. Longtermism lays bare that the EAs’ method is really a way to maximize on looking clever while minimizing on expertise and accountability. Even if the thing you gave a 57 percent chance of happening never happens, you can still claim you were right. These expected value pronouncements thus fit the most philosophically rigorous definition of bullshit.

Moreover, if applying expected value thinking to aid is dodgy, applying it to the remote future gets downright supervillainous. When you truly believe that your job is to save hundreds of billions of future lives, you’re rationally required to sacrifice countless current lives to do it. Remember SBF’s wager: A longtermist must risk the extinction of humanity on a coin flip, double or nothing, over and over again. MacAskill sometimes tries to escape this murderous logic with bullet-pointed musings about why violating rights is almost never the best way of creating a better world. In his longtermist book, he makes this case in a few wan paragraphs. But you can’t disown your party trick the moment before it breaks the punch bowl.

Despite its daffiness and its dangers, longtermism also found a ready-made audience in EA’s aspiring heroes. (“You Can Shape the Course of History” is the name of a chapter in MacAskill’s longtermist book.) At their best, EAs are well-meaning people who aspire to rigorous analysis. But EA doesn’t always bring out their best. If nerdy young adults see that they can get money or status or sex by intoning on Very Important Things while pulling numbers out of their pants, at least some will start pulling. All the usual hierarchical effects of in-groups will kick in, like groupthink and bullying (and, tragically, the alleged abuse of young EA women).

SBF also bankrolled longtermism lavishly. He put MacAskill and other EAs at the head of the Future Fund, meant to rescue humanity from “existential risks” like psychotic robots and planet-killing asteroids. The EAs got from SBF more than they’d ever dreamed: a billion dollars to save the world. But SBF also turned into their undoing. The EAs at the Future Fund had been warned for years about SBF. The revelation of his enormous financial frauds crashed the fund and decisively ended the EAs’ pose of being experts on risk. As the economist Tyler Cowen remarked on the Future Fund and SBF:

Pungent in theory, ruinous in practice. What more proof could a rational person need?

The billionaires have bought a lot of brains: Many people in Silicon Valley and around the world now call themselves effective altruists. Is there any way they might become Responsible Adults?

Some tech moguls may be unreachable. So many of them seem to be aging children, trying to play Minecraft with our world. They can always buy the tongues that tell them they’re right.

We might have more hope for some EA leaders. Ord now says he has found a math proof that requires caution about “doing the most good.” Karnofsky has worried aloud that EAs don’t know what the hell they’re doing. More transparency from them would help to build trust. If GiveWell is going to keep its pitch, it should pair every “lives saved” guess with a “lives ended” guess, and it should declare all of its uncertainties up front. Philosophers like MacAskill should publish complete accounts of all the money that has been spent on them and why they thought this was for humanity’s eternal good.

Yet transparency isn’t accountability. SBF’s company is being forced to return money to the investors who were misled. What should GiveWell and the institutions of EA do?

Will GiveWell empower any poor people that it might have harmed to file a grievance? And what will it say to all the donors who took its pitches literally? What about the young people who relied on the EA counseling service to go into a career that the service will no longer recommend for them? Will they at least get an apology?

My real hope is for the young people I know who truly want to work for a better world. They’re craving to do something meaningful, like poverty relief or pandemic preparation or AI safety. That’s so admirable, and they’re so impressive. I hope they’ll move into positions of real responsibility. When they get there, what should their philosophy be?

My thought is that what they need first is not so much a philosophy as a good look into the eyes of the people who might be affected by their decisions. That’s what changed my path in Bali—a sense of the reality of others, whose lives are just as valuable as our own. But even that may not be enough for my students in their future jobs when they’re busy making big decisions every day. Here are two tests that any of us can do to keep ourselves accountable.

Call the first the “dearest test.” When you have some big call to make, sit down with a person very dear to you—a parent, partner, child, or friend—and look them in the eyes. Say that you’re making a decision that will affect the lives of many people, to the point that some strangers might be hurt. Say that you believe that the lives of these strangers are just as valuable as anyone else’s. Then tell your dearest, “I believe in my decisions, enough that I’d still make them even if one of the people who could be hurt was you.”

Or you can do the “mirror test.” Look into the mirror and describe what you’re doing that will affect the lives of other people. See whether you can tell yourself, with conviction, that you’re willing to be one of the people who is hurt or dies because of what you’re now deciding. Be accountable, at least, to yourself.

Some EAs may still tell themselves that their lives are more important than other people’s lives because of all the good they will do for the world. For anyone who thinks like that, be accountable for those convictions. Tell your dearest exactly how many human lives you think your own life is worth. Publish your “gearing ratio” on your website, and open it for comments. Add the number of people that you calculate you’ve killed already.

My friend Aaron is a fine philosopher and a lifelong surfer. A dozen years ago, he made it to Indonesia and traveled up from a beach on Nias to villages near Lagundri Bay. He has now been back many times and has built up relationships, including one with a local leader named Damo. Aaron and Damo have become close, and they talk a lot. Aaron knows he’ll never be part of the island, that it’s not his life. But when Damo persuaded his village to put in water tanks and toilets, Aaron volunteered to help with planning. When Aaron got an advance on a book contract, the money went with him on his yearly trip to the island.

No billionaires, no hype, no heroes. Aaron is trying his best to shift his power to Damo and to the people on the island. Aaron will talk about the island if you ask him, but he never brags. And he’s accountable to the people there—in the way all of us are accountable to the real, flesh-and-blood humans we love.

Source : Wired