This past Monday, about a dozen engineers and executives at data science and AI company Databricks gathered in conference rooms connected via Zoom to learn if they had succeeded in building a top artificial intelligence language model. The team had spent months, and about $10 million, training DBRX, a large language model similar in design to the one behind OpenAI’s ChatGPT. But they wouldn’t know how powerful their creation was until results came back from the final tests of its abilities.

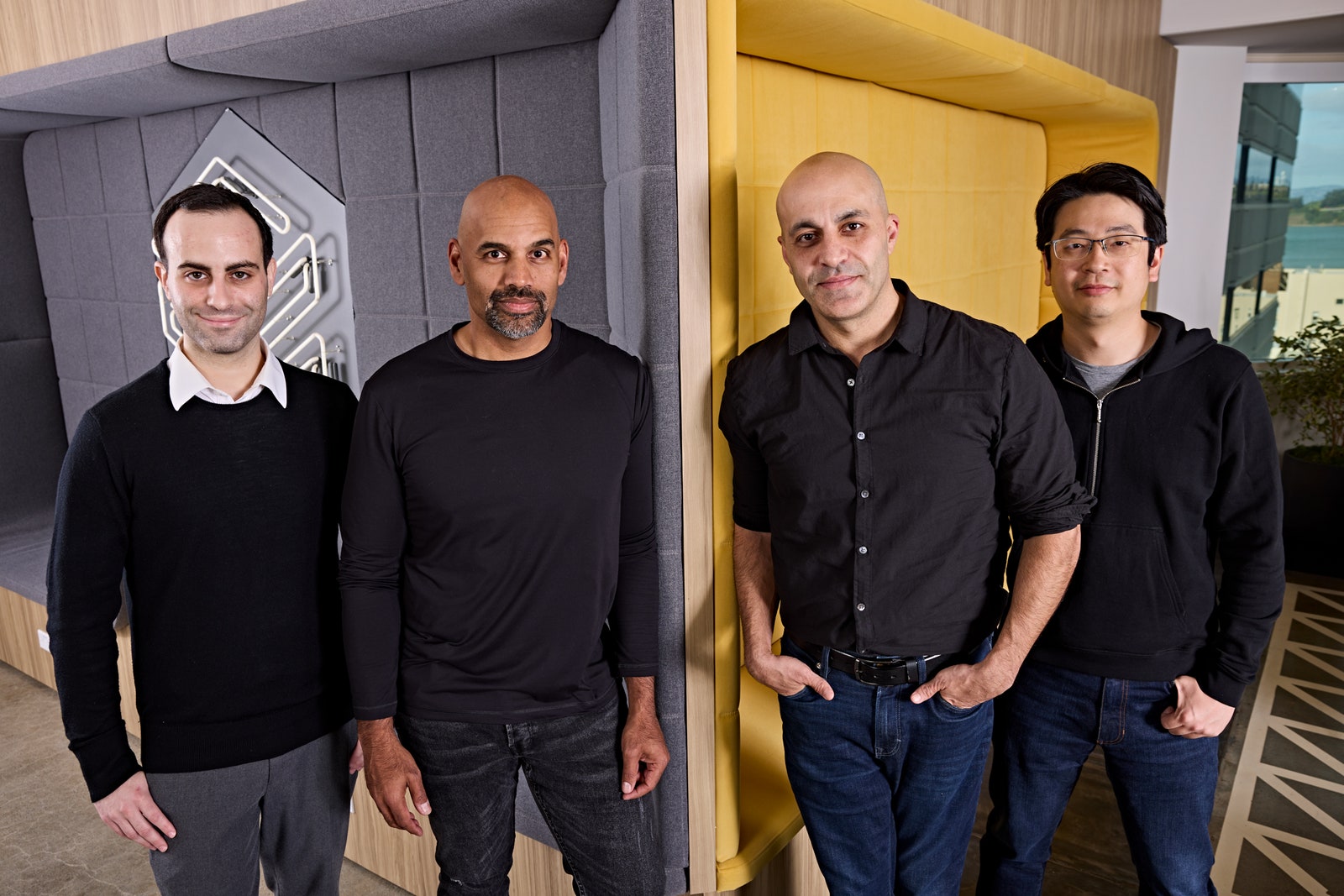

“We’ve surpassed everything,” Jonathan Frankle, chief neural network architect at Databricks and leader of the team that built DBRX, eventually told the team, which responded with whoops, cheers, and applause emojis. Frankle usually steers clear of caffeine but was taking sips of iced latte after pulling an all-nighter to write up the results.

Databricks will release DBRX under an open source license, allowing others to build on top of its work. Frankle shared data showing that across about a dozen or so benchmarks measuring the AI model’s ability to answer general knowledge questions, perform reading comprehension, solve vexing logical puzzles, and generate high-quality code, DBRX was better than every other open source model available.

It outshined Meta’s Llama 2 and Mistral’s Mixtral, two of the most popular open source AI models available today. “Yes!” shouted Ali Ghodsi, CEO of Databricks, when the scores appeared. “Wait, did we beat Elon’s thing?” Frankle replied that they had indeed surpassed the Grok AI model recently open-sourced by Musk’s xAI, adding, “I will consider it a success if we get a mean tweet from him.”

To the team’s surprise, on several scores DBRX was also shockingly close to GPT-4, OpenAI’s closed model that powers ChatGPT and is widely considered the pinnacle of machine intelligence. “We’ve set a new state of the art for open source LLMs,” Frankle said with a super-sized grin.

By open-sourcing, DBRX Databricks is adding further momentum to a movement that is challenging the secretive approach of the most prominent companies in the current generative AI boom. OpenAI and Google keep the code for their GPT-4 and Gemini large language models closely held, but some rivals, notably Meta, have released their models for others to use, arguing that it will spur innovation by putting the technology in the hands of more researchers, entrepreneurs, startups, and established businesses.

Databricks says it also wants to open up about the work involved in creating its open source model, something that Meta has not done for some key details about the creation of its Llama 2 model. The company will release a blog post detailing the work involved to create the model, and also invited WIRED to spend time with Databricks engineers as they made key decisions during the final stages of the multimillion-dollar process of training DBRX. That provided a glimpse of how complex and challenging it is to build a leading AI model—but also how recent innovations in the field promise to bring down costs. That, combined with the availability of open source models like DBRX, suggests that AI development isn’t about to slow down any time soon.

Ali Farhadi, CEO of the Allen Institute for AI, says greater transparency around the building and training of AI models is badly needed. The field has become increasingly secretive in recent years as companies have sought an edge over competitors. Opacity is especially important when there is concern about the risks that advanced AI models could pose, he says. “I’m very happy to see any effort in openness,” Farhadi says. “I do believe a significant portion of the market will move towards open models. We need more of this.”

Databricks has a reason to be especially open. Although tech giants like Google have rapidly rolled out new AI deployments over the past year, Ghodsi says that many large companies in other industries are yet to widely use the technology on their own data. Databricks hopes to help companies in finance, medicine, and other industries, which he says are hungry for ChatGPT-like tools but also leery of sending sensitive data into the cloud.

“We call it data intelligence—the intelligence to understand your own data,” Ghodsi says. Databricks will customize DBRX for a customer or build a bespoke one tailored to their business from scratch. For major companies, the cost of building something on the scale of DBRX makes perfect sense, he says. “That’s the big business opportunity for us.” In July last year, Databricks acquired a startup called MosaicML, that specializes in building AI models more efficiently, bringing on several people involved with building DBRX, including Frankle. No one at either company had previously built something on that scale before.

DBRX, like other large language models, is essentially a giant artificial neural network—a mathematical framework loosely inspired by biological neurons—that has been fed huge quantities of text data. DBRX and its ilk are generally based on the transformer, a type of neural network invented by a team at Google in 2017 that revolutionized machine learning for language.

Not long after the transformer was invented, researchers at OpenAI began training versions of that style of model on ever-larger collections of text scraped from the web and other sources—a process that can take months. Crucially, they found that as the model and data set it was trained on were scaled up, the models became more capable, coherent, and seemingly intelligent in their output.

Seeking still-greater scale remains an obsession of OpenAI and other leading AI companies. The CEO of OpenAI, Sam Altman, has sought $7 trillion in funding for developing AI-specialized chips, according to The Wall Street Journal. But not only size matters when creating a language model. Frankle says that dozens of decisions go into building an advanced neural network, with some lore about how to train more efficiently that can be gleaned from research papers, and other details are shared within the community. It is especially challenging to keep thousands of computers connected by finicky switches and fiber-optic cables working together.

“You’ve got these insane [network] switches that do terabits per second of bandwidth coming in from multiple different directions,” Frankle said before the final training run was finished. “It’s mind-boggling even for someone who’s spent their life in computer science.” That Frankle and others at MosaicML are experts in this obscure science helps explain why Databricks’ purchase of the startup last year valued it at $1.3 billion.

The data fed to a model also makes a big difference to the end result—perhaps explaining why it’s the one detail that Databricks isn’t openly disclosing. “Data quality, data cleaning, data filtering, data prep is all very important,” says Naveen Rao, a vice president at Databricks and previously founder and CEO of MosaicML. “These models are really just a function of that. You can almost think of that as the most important thing for model quality.”

AI researchers continue to invent architecture tweaks and modifications to make the latest AI models more performant. One of the most significant leaps of late has come thanks to an architecture known as “mixture of experts,” in which only some parts of a model activate to respond to a query, depending on its contents. This produces a model that is much more efficient to train and operate. DBRX has around 136 billion parameters, or values within the model that are updated during training. Llama 2 has 70 billion parameters, Mixtral has 45 billion, and Grok has 314 billion. But DBRX only activates about 36 billion on average to process a typical query. Databricks says that tweaks to the model designed to improve its utilization of the underlying hardware helped improve training efficiency by between 30 and 50 percent. It also makes the model respond more quickly to queries, and requires less energy to run, the company says.

Open Up

Sometimes the highly technical art of training a giant AI model comes down to a decision that’s emotional as well as technical. Two weeks ago, the Databricks team was facing a multimillion-dollar question about squeezing the most out of the model.

After two months of work training the model on 3,072 powerful Nvidia H100s GPUs leased from a cloud provider, DBRX was already racking up impressive scores in several benchmarks, and yet there was roughly another week’s worth of supercomputer time to burn.

Different team members threw out ideas in Slack for how to use the remaining week of computer power. One idea was to create a version of the model tuned to generate computer code, or a much smaller version for hobbyists to play with. The team also considered stopping work on making the model any larger and instead feeding it carefully curated data that could boost its performance on a specific set of capabilities, an approach called curriculum learning. Or they could simply continue going as they were, making the model larger and, hopefully, more capable. This last route was affectionately known as the “fuck it” option, and one team member seemed particular keen on it.

While the discussion remained friendly, strong opinions bubbled up as different engineers pushed for their favored approach. In the end, Frankle deftly ushered the team toward the data-centric approach. And two weeks later it would appear to have paid off massively. “The curriculum learning was better, it made a meaningful difference,” Frankle says.

Frankle was less successful in predicting other outcomes from the project. He had doubted DBRX would prove particularly good at generating computer code because the team didn’t explicitly focus on that. He even felt sure enough to say he’d dye his hair blue if he was wrong. Monday’s results revealed that DBRX was better than any other open AI model on standard coding benchmarks. “We have a really good code model on our hands,” he said during Monday’s big reveal. “I’ve made an appointment to get my hair dyed today.”

Risk Assessment

The final version of DBRX is the most powerful AI model yet to be released openly, for anyone to use or modify. (At least if they aren’t a company with more than 700 million users, a restriction Meta also places on its own open source AI model Llama 2.) Recent debate about the potential dangers of more powerful AI has sometimes centered on whether making AI models open to anyone could be too risky. Some experts have suggested that open models could too easily be misused by criminals or terrorists intent on committing cybercrime or developing biological or chemical weapons. Databricks says it has already conducted safety tests of its model and will continue to probe it.

Stella Biderman, executive director of EleutherAI, a collaborative research project dedicated to open AI research, says there is little evidence suggesting that openness increases risks. She and others have argued that we still lack a good understanding of how dangerous AI models really are or what might make them dangerous—something that greater transparency might help with. “Oftentimes, there’s no particular reason to believe that open models pose substantially increased risk compared to existing closed models,” Biderman says.

EleutherAI joined Mozilla and around 50 other organizations and scholars in sending an open letter this month to US secretary of commerce Gina Raimondo, asking her to ensure that future AI regulation leaves space for open source AI projects. The letter argued that open models are good for economic growth, because they help startups and small businesses, and also “help accelerate scientific research.”

Databricks is hopeful DBRX can do both. Besides providing other AI researchers with a new model to play with and useful tips for building their own, DBRX may contribute to a deeper understanding of how AI actually works, Frankle says. His team plans to study how the model changed during the final week of training, perhaps revealing how a powerful model picks up additional capabilities. “The part that excites me the most is the science we get to do at this scale,” he says.

Source : Wired