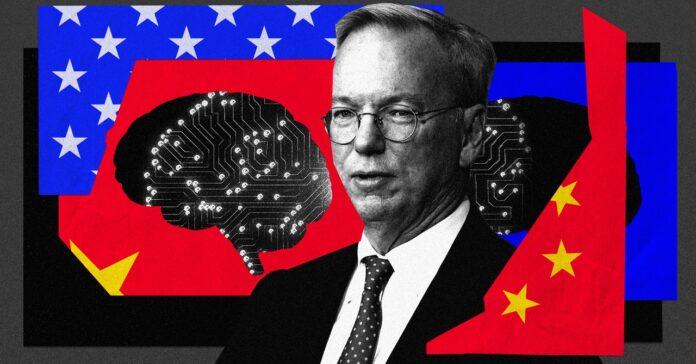

In November 2019, the US government’s National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI), an influential body chaired by former Google CEO and executive chairman Eric Schmidt, warned that China was using artificial intelligence to “advance an autocratic agenda.”

Just two months earlier, Schmidt was also seeking potential personal connections to China’s AI industry on a visit to Beijing, newly disclosed emails reveal. Separately, tax filings show that a nonprofit private foundation overseen by Schmidt and his wife contributed to a fund that feeds into a private equity firm that has made investments in numerous Chinese tech firms, including those in AI.

When the NSCAI issued its full findings in 2021, Schmidt and the NSCAI’s vice chairman said in a statement that “China’s plans, resources, and progress should concern all Americans,” and warned that “China’s domestic use of AI is a chilling precedent for anyone around the world who cherishes individual liberty.”

The 2019 email communications, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by the Tech Transparency Project (TTP), a nonprofit research initiative that tracks tech industry influence, show staff at Schmidt Futures, a philanthropic venture, asking NSCAI employees to help identify “possible engagements [Schmidt] might have on AI, in a personal capacity.” The names are redacted, but an NSCAI staff member replies, “Sure thing, happy to help out.” One person is tasked with coming up with “interesting companies in Beijing.”

It is unclear what meetings, if any, occurred in China as a result of the discussions, or whether such meetings might have translated into business dealings. However, the messages add detail to what appears to be a complicated relationship between Schmidt and America’s chief geopolitical rival. They also reflect the paradox of rivalry and interdependence that characterizes the dynamics between the world’s two most powerful nations.

Flight records previously obtained by TTP show that a Gulfstream flew from Google’s home hanger in November 2019. A day later, press reports suggest Schmidt, who was in China for the Bloomberg New Economy Forum, dined with Kai-Fu Lee, ex-head of Google China and a prominent Chinese entrepreneur and investor. The pair told a Bloomberg reporter at the time that they were “just catching up.”

Tax filings for 2019 show that the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation, a nonprofit overseen by the billionaire and his wife, had invested almost $17 million in a fund that feeds into an investment firm then called Hillhouse Capital, which invests in a number of prominent Chinese tech and AI companies, among other businesses. In October 2016, Hillhouse reportedly launched an AI investment fund with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, a state-run institution. In 2017, Hillhouse led a funding round of $55 million in the Chinese AI company Yitu, a startup that would soon be repeatedly blacklisted by the US government for allegedly supplying face recognition technology used for surveillance in China.

The final NSCAI report includes a section on promoting “International Digital Democracy” initiatives. It provides a handful of suggestions for how to “develop, promote, and fund” digital ecosystems, including partnerships with the private sector—citing Hillhouse as a positive example.

There is no indication that Schmidt’s visit to China is related to the investments made by Hillhouse, and no evidence that Schmidt used his role at the NSCAI to further his own business goals. But even as separate matters, the emails and investments associated with Schmidt underscore the potential conflicts of interest he may have encountered in his role as NSCAI chair, says Katie Paul, director of TTP.

The NSCAI’s findings helped foster an increasingly hawkish China strategy among US policymakers and politicians. As China’s tech industry has become more ambitious in recent years, both the Trump and Biden administrations have tightened investment rules and imposed sanctions aimed at curbing China’s technological march. In 2022, for instance, the US limited the country’s access to the chips and chipmaking technology needed to develop the most advanced AI algorithms. The US government has also ratcheted up spending on AI and related technologies to counter China’s rise. A 2023 report from an institute affiliated with Stanford found that government contract spending on AI increased almost 2.5-fold from 2017. A Brookings report found that the potential future value of federal contracts involving AI increased almost 1,200 percent between August 2022 and August 2023. The CHIPS and Sciences Act, designed to help the US chip companies become more competitive and resilient, will pump $50 billion into domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The president’s proposed budget for 2025 earmarks $3 billion for federal use of AI.

The emails and potential investments associated with Schmidt are “further evidence that people with financial interests in AI are trying to shape the US government’s AI policy,” says Paul.

Schmidt’s views on China may well have evolved since 2019. But tax filings for 2022, the most recent on record, show that the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation still held an investment of more than $16 million in the fund that is managed by Hillhouse. Schmidt also has a significant stake in Alphabet, Google’s parent company, which competes with Chinese AI firms.

Schmidt declined to comment, but a source familiar with the situation, who asked to remain anonymous because of the political sensitivities involved, says that Schmidt’s 2019 China trip was “not planned, organized, managed, or paid for by NSCAI.” The source adds that Schmidt does not have direct control of the investment fund that feeds into Hillhouse, and that its investment choices are independently managed. “Eric has always complied with the necessary disclosure requirements when he’s served in a government capacity,” the source says. Hillhouse also declined to comment.

Since stepping away from Google in 2011, Schmidt has become an enormously influential figure in US foreign policy circles, using his own fortune to help fund influential research on a range of technology-related issues. He has also invested in many companies that are affected by government policies on emerging technologies.

Nearly a decade before becoming chair of the NSCAI, Schmidt was appointed a member of President Obama’s Council of Advisers on Science and Technology after endorsing his presidential bid. He was named by then secretary of defense Ashton Carter to serve as chairman of the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Board between 2016 and 2020. In 2022, Protocol reported that between 2016 and 2021, Schmidt’s firm, Innovation Endeavors, had invested in companies that received multimillion-dollar federal contracts, including the AI software firm Rebellion Defense. CNBC also reported in 2022 that Schmidt and his private family foundation made a number of investments in AI companies after becoming chair of the NSCAI. In December 2022, Senator Elizabeth Warren wrote a letter to Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin expressing concern about Schmidt’s position.

Even while serving as chair of the NSCAI, Schmidt at times pushed for a more open approach to China. In 2019, for instance, he implicitly defended a Google plan to reenter the country with a censored version of its search engine code-named “Dragonfly.” He said that he had opposed Google’s decision to leave China in 2010 because he felt the company’s presence would “help change China to be more open.”

“It might be fair to say—given Schmidt’s past role championing Google’s censorship of search—he has a history of playing both sides on China,” says Jack Poulson, executive director of Tech Inquiry, a tech industry accountability nonprofit.

The emails obtained by TTP mention that Schmidt would be accompanied on his trip by Henry Kissinger, the former national security adviser and US secretary of state who famously sought closer ties with China in the 1970s, during President Nixon’s administration. Kissinger was treated to high-level meetings with top Chinese officials as recently as 2023, as Beijing sought to engage with less hawkish voices.

After the NSCAI finished its work, Schmidt created the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP)—an organization modeled on the Cold War, Nelson Rockefeller-era Special Studies Project—to pick up the mantle. The SCSP declined to comment.

Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation and an adviser to the SCSP, says its work has been consistently tough on China. “I’ve never gotten a sense from them that they are pulling any punches towards China,” he says.

US-China relations became particularly strained during the Covid pandemic, but while rhetoric often echoes the Cold War, the relationship between the world’s two dominant superpowers is itself complex. The two nations remain dependent on one another technologically, with the US tapping Chinese talent and manufacturing to power its tech industry, and China drawing on inventions and technologies sourced from the West to fuel its own.

Schmidt has continued to sound the alarm about China’s AI rise. In late 2022, he was tapped to serve on a new National Security Commission on Biotechnology. In April 2023 he spoke out against a proposed six-month pause on the development of AI due to the risks, warning that it would “simply benefit China.”

That same month, Schmidt acknowledged the double-edged nature of America’s relationship with China at an event organized by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a defense think tank. “China is a new kind of competitor, in the sense that we can rely on them for some things, but they are a competitor in others,” he said. “Notice I didn’t say enemy.”

Source : Wired