In the fall of 2020, bored and restless in Covid-restricted Spain, Ángel Guerra doodled a dream car. The automotive designer, then 38, wanted to make a tribute to his first four-wheeled love: the time-traveling DeLorean DMC-12 that rolled out of a cloud of steam in Back to the Future. The sketch that took shape on Guerra’s computer had all the iconic elements of the 1980s original—gull-wing doors, stainless-steel cladding, louver blades over the rear window, a rakish black side stripe—plus a few modern touches. Guerra smoothed out the folded-paper angles, widened the body, stretched the wheel arches to accommodate bigger rims and tires. After two weeks, he decided he liked this new DeLorean enough to stick it on Instagram.

The post blew up. Gearheads raved about the design. The music producer Swizz Beatz DM’d Guerra to ask how much it would cost to build. Guerra started to think that maybe his sketch should become a real car. He reached out to a Texas firm called DeLorean Motor Company, which years earlier had acquired the original DeLorean trademarks, but was gently rebuffed. The design seemed destined to live in cyberspace forever. Then, by some algorithmic magic, a different kind of DeLorean showed up on Guerra’s Instagram feed in the spring of 2022—a human DeLorean by the name of Kat. Her posts showcased her love for her puppy, hair dye, and above all her late father, John Z. DeLorean. Although the general public often remembers him as a high-flying CEO with fabulous hair and a surgically augmented chin who went down in a federal sting operation, Guerra chiefly thought of him as a brilliant engineer. He sent Kat a message with some kind words about her dad and a link to the design. Kat saw it and got stoked.

Kat DeLorean is a frequently stoked type of person. At the time, she had recently dyed her long hair in rainbow colors to, in her words, “create the rainbows in my heart on my head.” Yet for much of her life, her relationship to the DeLorean name had been an unhappy one. When people asked why she didn’t own a DMC-12, she would reply: “If there was an iconic representation of your entire life falling apart, would you park it in your driveway?” She would say, only half-jokingly, that the initials stood for “Destroy My Childhood.” A fortysomething cybersecurity professional, Kat lived in a ramshackle farmhouse in New Hampshire with her husband and a few kids. But when Guerra’s note arrived, she was undergoing a pandemic- and work-stress-induced reevaluation of her life’s purpose. She was dreaming up ways to reclaim her father’s legacy. She wanted to launch an engineering education program in his name.

One thing she insisted she didn’t want was to start a car company. It was a car company, after all, that had ruined her father. But then something happened that changed her mind. In April 2022, the Texas company that had given Guerra the cold shoulder announced it would soon reveal a new DeLorean. Kat kept her feelings about this to herself only briefly. First she drew attention to Guerra’s design, posting it on Instagram. (“A timeless classic given the treatment it deserves!”) Two days later, she made her feelings explicit: “@deloreanmotorcompany Is not John DeLorean’s Company,” she wrote. “He despised you.” Details about the new Texas DeLorean emerged a few days after that: Called the Alpha5, it would have four seats instead of two, would reportedly be built mostly from aluminum rather than stainless steel, and would be available in red. Like many DeLorean purists, Kat hated it.

As people kept messaging her about the pretty design they’d seen on her Instagram feed—some even offered to help build it—a new plan took shape. Kind of a crazy one. She started to think: Why not build one car and film the process of building it for the engineering students? Eventually that turned into: Why not make several and sell them to fund the engineering program? But then why not …

As Kat’s ideas tend to do, this one snowballed: an engineering program in every state, funded by cars; her mind could easily leap from there to notions of rebuilding the industrial Midwest and rejiggering American work culture in general, the ultimate realization of her oft-stated belief that “everyone should have the same opportunity to live their dream.” John DeLorean had plotted to return to the car market until the day he died. Now, she thought, shouldn’t she give the nerds what they wanted? Fine, she had zero experience running a car company, but she could find people for that, and anyway she’d spent, by her estimate, thousands of hours talking engine design with her dad. She described herself as having “gasoline in her veins.”

Which didn’t really change the fundamentals, including how difficult and outrageously expensive it is to bring a car to market, not to mention the itchy point that the “DeLorean” branding technically belonged to someone else. Never mind all that. Kat was a DeLorean—a name, for good or ill, associated with wild ambition.

John Z. DeLorean was a suave, swashbuckling General Motors executive who dated young models and palled around with celebrities. He became automotive royalty in the mid-1960s, when he had the idea of sticking a bigger engine into an “old lady” car, thereby reinventing the Pontiac brand and launching the “muscle car” era. But DeLorean felt stifled at GM, and he dreamed of building what he called an “ethical car”: safe, reliable, affordable, and environmentally friendly. He left the company in 1973, the same year he married the supermodel Cristina Ferrare, his third wife. Two years later, he founded the DeLorean Motor Company. And two years after that, DeLorean and Ferrare, who shared an adopted 6-year-old son named Zach, welcomed their baby daughter Kathryn.

The original DeLorean Motor Company’s brief and turbulent history spanned Kathryn’s early childhood. She has few direct memories of the time her dad spent assembling a team of mavericks and dreamers enticed by the idea of building a whole car company from a blank sheet of paper. With a generous investment from the British government, DeLorean opted to put his factory outside Belfast, Northern Ireland. This was during the Troubles, when the idea of Catholics and Protestants working side-by-side seemed impossible. But, for a time, it worked. “There was a bog, then there was a factory, then there were jobs,” William Haddad, an executive for the company, recalled in a 1985 interview. “It was really exciting as hell.”

It also happened to be an era of inflation and soaring gas prices. An inexperienced workforce and frequent bomb scares further complicated production. Timelines slipped, production costs ballooned, demand collapsed, debt accrued. The company had to recall a couple thousand cars. DeLorean’s original vision, described by one classic car aficionado as a $12,000 “Corvette killer” featuring “unprecedented safety and efficiency attributes,” morphed into a $25,000 vehicle with few of those qualities. Then, in October 1982, with little Kathryn approaching her fifth birthday, came the world-famous denouement: John DeLorean caught on tape with an FBI informant in a room with nearly 60 pounds of cocaine. The informant had pitched the sale of the drugs as a way to raise enough money to save DeLorean’s struggling company.

Kat was 6 when her dad’s high-profile trial ended in an acquittal in the late summer of 1984, on the grounds of entrapment. Her dad’s company and career were destroyed, as he ruefully asked reporters outside the courtroom: “I don’t know, would you buy a used car from me?” Also destroyed was a kind of childhood idyll for Kat, who went very suddenly from living in an intact, wealthy, and famous New York City family—complete with an apartment on Fifth Avenue worth $30 million in today’s dollars—to being a child of bicoastal divorce. Within the year, her mother was remarried to a television executive, and Kat was mostly living in California. She was allowed 10 minutes a day on the phone with her dad back East, which she extended by enlisting his help with math homework.

Back to the Future came out a year after John’s acquittal. Although a studio official had pushed the filmmakers to use a Mustang for their time machine—Ford was willing to pay handsomely for the product placement—the screenwriter reportedly replied, “Doc Brown doesn’t drive a fucking Mustang.” The selection of the DMC-12 for the honor (cue Marty McFly: “Are you telling me that you built a time machine out of a DeLorean?”) prompted John to write a thank-you letter to the director and screenwriter, who he said had “all but immortalized” his car. Unlike Guerra, Kat has no recollection of seeing Back to the Future for the first time. “It just felt like the movies were always there, always a part of my life,” she told me.

As a teenager, Kat was allowed to choose which parent to live with, and she picked her dad. She spent her high school years on a farm in Bedminster, New Jersey. (The exact site that would later become the Trump National Golf Club Bedminster.) She rode dirt bikes around the vast property, did musical theater in private school, and sometimes endured cocaine jokes from her peers. Her best friend at the time taught Kat how to fix her own computer and inspired her habit of tinkering with the machines.

She modeled for a few years after high school but stayed geeky, spending her nights on hacking competitions. Then, in her early twenties, pregnant with her first child from a brief first marriage, she decided she didn’t want to raise her son in the world she’d known as the daughter of a supermodel. (These days she refers to “that world” of fabulous wealth from an almost mystified remove, as if the visit on the Schwarzeneggers’ private jet and the pajama party with Kourtney Kardashian had happened to someone else.) Instead, she took an IT internship at Countrywide Financial—later to be acquired by Bank of America—and started working her way up. She met a systems engineer named Jason Seymour at a company Christmas party and married him a little more than a month later at a drive-thru wedding chapel in Las Vegas. (Jason had wanted an Elvis impersonator to officiate, but he wasn’t available.) The following year, in 2005, her father died. John DeLorean had spent some of his final months attempting to trademark the name “DeLorean Automobile Company” through a company called Ephesians 6:12, which he’d set up with Kat and Zach as co-owners. (The name is a reference to a biblical verse about struggling “against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”) But he passed away before application could be approved, so it was officially listed as “abandoned.”

John’s death devastated Kat. Although she remained fiercely proud of her father and kept attending car shows in her capacity as a DeLorean, she went professionally by her married name, Seymour, and maintained a separation between those two identities. But in the 2020s, as the DMC-12’s 40th anniversary approached, John’s name was popping up in documentaries and movies again, and Kat was not happy with some of the portrayals depicting him as a kind of narcissistic hustler. She became determined to get the positive story of John DeLorean out.

As a big “trust the universe” person, she believed it was meaningful that an actual angel (Guerra) had shown up in her life with a design. So through the summer and fall of 2022, Kat’s ambitions took the shape of a car. The model would be called JZD, her dad’s initials, and the company would pour the sales revenue into more education programs—expanding into underserved areas in the industrial Midwest where her dad made his career. She resisted even calling the venture a “car company”; she much preferred to say it was a “dream-empowerment company fueled by automobiles,” in the same way Girl Scouts is a youth-empowerment organization fueled in part by cookies.

Whatever the company was, the New Hampshire farmhouse turned into its de facto headquarters. Kat and Jason took video meetings, recruited talent, and entertained wild ideas about what a new car “with DeLorean DNA” could do. (She joked: “Leave it to me to start a car company right when nepo babies are a thing.”) Could they source sustainable stainless steel for their first car by melting down old appliances? Could they use recycled computer chips to control it? Could they make virtual-reality manufacturing labs for their students, to assemble first a virtual car and then a real one? This was going to be a brand-new kind of car company—among the first ever founded by a woman and likely the first intended to be a not-for-profit.

With these big visions came big promises. In August 2022, Kat posted a screenshot from John’s final automotive business plan, which promised to “shake the automotive world” with a car that would kick off “an affair with man and machine at a price point that will be affordable.” She expressed an intent to follow these wishes with her own car company. The company’s name: DeLorean Next Generation.

The news spread, first with an item on Fox News and then in outlets all over the world. Jason was so high on enthusiasm for the new company, and pride in his wife’s ambition, that he dashed off a public promise on the DNG Motors Instagram account. “UNVEILED SEPTEMBER 13, 2023,” read an image of white text on a black background, with Jason’s caption: “DeLorean is back in the Motor City.” He’d just committed them to building a car for the Detroit Auto Show. When Kat saw the post, she flipped out.

Soon afterward, the DeLorean Motor Company in Texas sent Kat a cease-and-desist, demanding she stop using the DeLorean name for her planned car. She and Jason had their lawyer send a reply asserting their rights and expressing their willingness to litigate, and kept going.

DeLorean Motor Company sits in a squat building off a tangle of highways in suburban Houston—you drive past some shabby lots and fields, and then the 1980s spring up around a curve in the road, where a retro-looking DMC logo looms over a row of DMC-12s in the parking lot. You might even spot a JIGAWAT license plate there. Inside the garage/warehouse is an array of disembodied gull-wing doors that evoke a flock of injured birds. Old covers of Deloreans magazines stare out from frames in the showroom.

This is the realm of Stephen Wynne, a Liverpool-born mechanic who has devoted his life to DeLorean the car—to the point of driving his son Cameron to kindergarten in DMC-12s that appeared in Back to the Future. Wynne is less impressed with DeLorean the man, however. “I have more respect for the team that he put together,” he says. “All you hear about is John DeLorean and not the team, and that, to me, is not right.” John was, Wynne said, ahead of his time as an engineer. But: “He made the company, and he also, you know, killed the company in the end.”

It was Wynne who picked up the pieces, effectively securing a monopoly on the small, strange market for DeLorean parts. This was not a decision about preserving someone else’s legacy; it was about securing his own future. “It felt to me like, to control my destiny, going forward, it was to have control of the parts,” he told me in the shop as tools clanked against cars behind us. “If someone was going to get it, I wanted it to be me.” He founded the new DeLorean Motor Company in 1995.

Wynne considers the original buyers of the 1980s DeLorean to have been “entrepreneurial, outside-of-the-box-thinking type people,” with something a “little bit different about them”—less interested in owning a really fast sports car than a piece of cultural history. (The original DeLorean did 0 to 60 in about 10.5 seconds, something my used Hyundai can easily beat.) “We believe that there’s much more wealth in that market these days,” Wynne says.

Over the years, Wynne and team made various plans to serve this market of “modern nerds” with new cars built mostly from original parts. But federal regulators were slow to relax the rules that said these historic replicas had to meet current safety standards, so the revival of the DMC-12—with its lack of airbags, a third brake light, and antilock brakes, for instance—never happened. Still, the company did a thriving business in parts sales and car service. It also made a good buck from the DeLorean brand, which it alternately licensed for apparel, video games, and the like, or zealously protected via cease-and-desists and lawsuits.

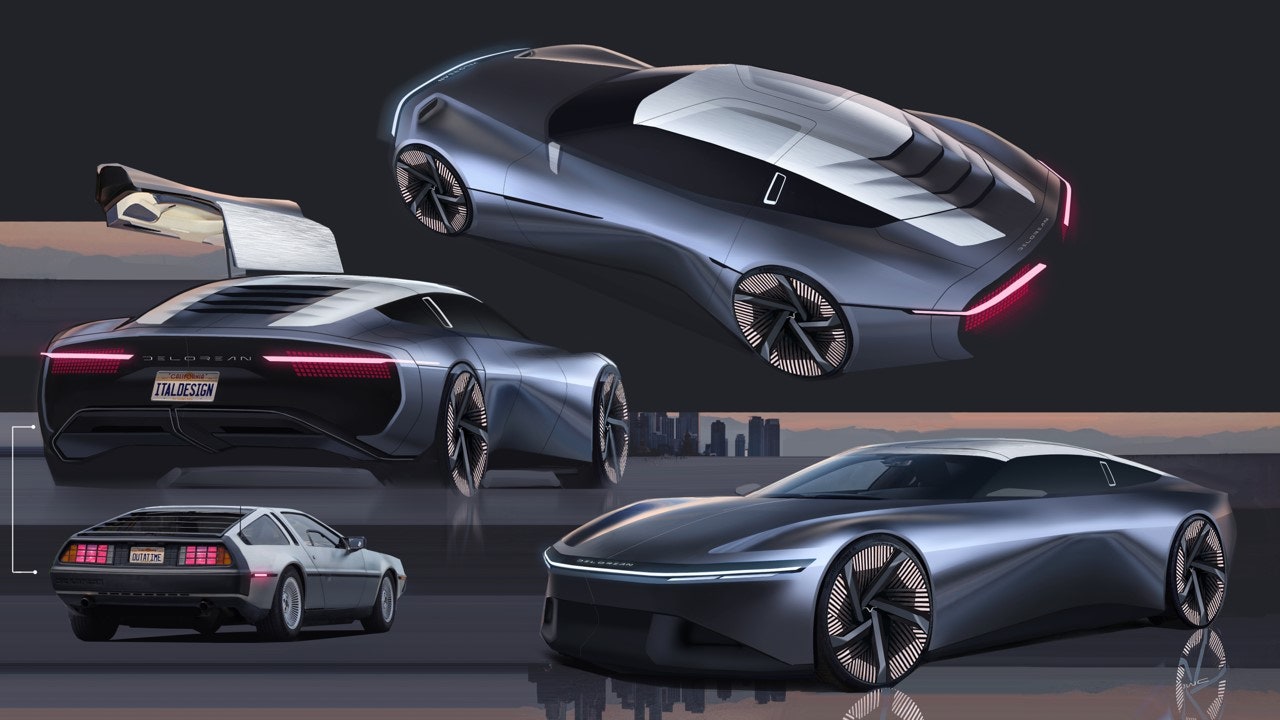

Finally, Wynne got to talking with a Tesla alum named Joost de Vries, who’d been involved in previous efforts to electrify the DeLorean. The DeLorean brand, de Vries argued, was so universally beloved, and startup costs for electric vehicles were so much less than even 15 years earlier, that they could partner up to build a brand-new electric DeLorean. Together they formed a San Antonio–based spinoff of DeLorean Motor Company, called DeLorean Motors Reimagined, with the Wynne family as the largest shareholders and de Vries as CEO. (Wynne’s son, the former time-traveling kindergartner, is now the companies’ chief brand officer.) De Vries would lead the development of the car, and funding would come largely from private investors. The company incorporated in Texas in November 2021 (smack in between when Guerra posted his design in late 2020 and when Kat got involved in mid-2022). Wynne and de Vries hired Italdesign, the same firm that had drafted the original DMC-12, to design the Alpha5.

DeLorean Motors Reimagined hoped to build 88 cars to start (88 mph being the speed at which Doc Brown’s DeLorean traveled through time), then about 9,500. The car would be “low volume, high-end, very exclusive, weird, wild technology,” according to de Vries, an imposing, bald Dutchman with the hard-charging swagger of the Silicon Valley executive he once was. “DeLorean was always attainable luxury. My price tag is not going to be attainable luxury.”

DeLorean Motors Reimagined went from founding to concept car within nine months. The company even bought a 15-second Super Bowl spot in February 2022, cryptically teasing the new car and setting off buzz in the automotive press. The Alpha5 premiered at the Pebble Beach auto show that August. It was only a concept, meant to show off design and technology, not a finished product that could operate on the road. But it was a real object that existed in the real world and was promised to be on sale to the public in 2024.

By that point, the JZD, Kat’s model, was still in the design phase, living for the most part in computers.

The steps to getting a new car from invention to production are standard, whether you’re General Motors, DeLorean Motors Reimagined, or DeLorean Next Generation. On average, the process takes about five years. You have to design and engineer the car; find suppliers for thousands of parts, from wheels to seats to instrument panels; get tools custom-made to stamp out your body panels; and find or build the facility and the workforce to put these things together. This is all before you can actually mass-produce something that resembles the original design.

So it is not at all unusual for a concept car to appear at an auto show and then for nothing resembling it to ever materialize on actual roads. A paint facility alone can set a company back hundreds of millions of dollars. This is in fact why the original DeLorean was stainless steel: John DeLorean couldn’t afford a paint plant. (His marketing genius, Kat says, was that “he made you all think it was intentional.”) John Z. DeLorean had his first prototype by 1976, within about a year of founding his company; the first DMC-12s went on sale in 1981.

Theoretically, then, it was possible to build a one-off JZD concept car—if not a production-ready prototype—in the 11 months Kat and Jason had between founding the company and the 2023 Detroit Auto Show. Kat projected confidence onstage at a Miami auto show in January 2023, while a digital rendering of the JZD zoomed along mountain roads on a screen behind her. But shortly after that appearance, she started getting stressed out about the timeline. Potential manufacturing partners were telling her it was wildly unrealistic. Even getting the doors to open and close the same way every time was its own feat of engineering, and Kat couldn’t tell them whether the car would run on gas, batteries, or both. (She wanted students to make that decision as part of an engineering challenge she had yet to set up.) Kat began to have visions of living the same arc of ambition and collapse that befell her father.

This was her preoccupation when she showed up on a warm March 2023 morning in Augusta, Georgia, as a special guest at a “DeLorean Day” event. Well before 8 am, she was stalking around the parking lot in a rainbow plaid skirt and a NERD (Northeast Region DeLorean Club) hoodie with Jason in tow, enthusing to fans about their cars, talking not just with her hands but sometimes with her feet. She literally jumped up and down after a green ’66 Pontiac GTO Tri-Power pulled onto the lot. She inspected the carburetors under the hood and declared that this model, in midnight blue, was her “ultimate dream car,” shout-laughing when the owner confessed to the absurd gas mileage—about 8 miles per gallon in the city—then apologizing, through laughter, for laughing.

By 8 am she was posted up behind a mic to discuss her father and her own plans. “My father was my best friend in the whole world,” she said. “In the summers, I sat and played gin rummy with him on the couch, to the point where there was a worn spot in each place where we sat—a big one and a little one.” She got teary-eyed during the Q&A period when a kid of maybe 10 told her of his plans to be a robotics engineer. He hoped, he said, to make cars that could turn into robots that could “help people and protect humans from like, anything bad that can happen.” She would later tell me that this moment and others like it in Augusta added up to a turning point for her—that “all of a sudden it was like, OK, whatever I have to do, whatever pain I have to go through, if it means building a car company, then I’m going to do it, because I want that moment every day for the rest of my life.”

And when a well-meaning questioner brought up the Alpha5, she spoke carefully through a tight smile. “That is being made by the company DeLorean Motor Company Texas, and they’re not affiliated at all with the family or the original car. And I think that’s about all I’m going to say about that one.”

When I asked Joost de Vries about Kat DeLorean’s efforts a few weeks later, he was less diplomatic. “There’s just something loose in her head,” he said. “Kat’s thing is illegal. And she’s being shut down.” He said in a later conversation that she would be “hammered with lawsuits” as soon as her car appeared at the Detroit Auto Show.

De Vries and I were in a bland tech office park in San Antonio, where he sat in his glass-walled office. He was well aware that the Alpha5 design was polarizing in the DeLorean community. (Some DeLorean forum users had groused that the model just looked like another Tesla with gull-wing doors; one called the whole effort “little more than slapping the name of a beloved car on an unrelated vehicle.”) He also knew the discouraging fate that had befallen many an EV brand before his. Other high-end EV companies such as Lucid, Rivian, and the failed-then-resurrected Fisker had burned through billions and missed production targets, and even market leader Tesla was then struggling to bring its hyped (stainless-steel) Cybertruck to market. DeLorean Motors Reimagined had hit supply-chain snags and cut its planned production run by more than half, to 4,000 cars. But de Vries had something most EV companies didn’t: a brand that much of the world already knew. “The only thing I need to do is put good product into an existing brand,” he said.

But the question, of course, is whose brand “DeLorean” really is. Both companies insist on their own rights to use it. And each calls the other’s claim transparently illegitimate.

Stephen Wynne registered and enforced trademarks on “DeLorean” and “DeLorean Motor Company” in the 2000s, as John’s trademarks were canceled or abandoned, and he has renewed and protected them ever since. Furthermore, in a 2015 settlement with John DeLorean’s estate, a woman named Sally Baldwin DeLorean, acting as John’s widow, acknowledged “the worldwide rights of DMC to use, register, and enforce any of the DeLorean Marks for any and all goods and services” related to cars, clothes, and “promotional items”—for which DMC paid her an undisclosed sum. So, yes, it is Kat’s name. But it’s someone else’s trademark, and it’s one she has never tried publicly to contest until now.

Kat’s argument includes that seemingly simple but possibly irrelevant part—it’s her name—but also a convoluted part. She doesn’t believe John actually ever married Sally. Nor do several people I spoke to from John’s orbit at the time, including his son, Zach, none of whom can recall John mentioning a marriage to her. Kat told me she searched for and never found a marriage certificate. Nor did a private detective she hired. (Sally Baldwin DeLorean’s lawyer did not return requests for comment, and attempts to reach her directly via listed phone numbers were unsuccessful.) John’s will names his son as executor. Zach, balking at the prospect of attorney’s fees, never actually filed the will. Kat contends that Baldwin’s settlement with the DeLorean Motor Company is illegitimate, as she was never in a position to act on behalf of the estate in the first place. What should have happened, Kat thinks, is for the US Patent and Trademark Office to reach out to her and Zach, as co-owners of Ephesians 6:12, about her dad’s pending application.

Then there is the question of infringement, a key standard for which is “likelihood of causing confusion.” Kat’s DeLorean Next Generation is not using the exact same set of words as Wynne’s DeLorean Motor Company, but it is fair to say, based on the Alpha5 question that Kat got in Augusta—and on a well-meaning Reddit commenter who’d tried to buy Kat’s car only to accidentally reserve an Alpha5—that some members of the public are indeed confused. Yet each side accuses the other of doing the confusing.

Both sides have told me a lawsuit is inevitable. No jury decision is guaranteed—determining “likelihood of confusion” itself involves a (confusing!) 13-factor test. But New Jersey trademark attorney Richard Catalina, who is not affiliated with either party, told me that the “stronger legal arguments” belong to the Texas company. “Trademark rights only accrue with use. If you’re not using the mark, you can lose your rights to it,” Catalina said.

“I just learned the. Craziest. Thing,” Kat told me on the phone last summer. She’d recently found the 1985 interview with William Haddad, the executive who’d found it “exciting as hell” how much good DeLorean Motor Company had achieved in Northern Ireland. Haddad had been crushed by the company’s collapse, and now, in 1985, called it a “scam” and John himself a thief. (John had always denied this and was never convicted of financial misdeeds.) But Haddad was wistful about John’s squandered ambition to locate factories where they could do the most social good. “If only he had done it … Can you imagine it?” Haddad mused in the interview.

Kat knew the Northern Ireland story well already, but Haddad had put John’s goal and his downfall in terms that suddenly clicked for her. She and Jason had been so caught up in the crazy timeline they’d set for themselves that they were risking following precisely her dad’s path—letting one car distract them from their bigger goal of supporting young engineers. “If my car company fails, that’s OK,” Kat said. Her goal had always been to create an education program for students who have “dreams that have been robbed from them,” she said. “And if I can’t do that with this car, then it’s not worth the car.”

One thing was obvious: They were moving too fast. Kat decided she would not unveil the prototype of the JZD until her father’s 100th birthday, in 2025. In the meantime, they would have students build a clay model for Detroit—not a full-size one, as automakers typically do during development, but one about the size of a shoebox—and debut it not at the Auto Show but concurrently at the Detroit Historical Society. Later on, they’d enlist students to help build a prototype of their Model JZD on top of a Corvette C8 platform, picking participants through an online contest in which students described their dreams. After that would come a separate line of cars under Project 42, involving a hand build of 42 completely customized cars. These would have a sales price of probably over a million dollars each (which would also include custom driving outfits and a motorcycle to go with each car). They’d use the proceeds to fund the education program. So if the Alpha5 was going to be “unattainable luxury” and its likely market rich tech bros, then these custom cars would be yet less attainable and probably serve a market of billionaires.

It’s been two years since DMC Texas and Kat DeLorean both announced their new car projects. Neither has sued the other yet, and both are cagey about plans to do so. Joost de Vries stepped down from the helm of DeLorean Motors Reimagined last October, for reasons the company won’t disclose. A lawsuit against de Vries and other DeLorean Motors Reimagined executives, in which de Vries’ former employer Karma Automotive accused him and others of stealing the EV maker’s intellectual property, was dismissed after a reported out-of-court settlement. Timelines have slipped enough now that Cameron Wynne won’t specify exactly when the Alpha5 will be on sale—he says sometime in 2025. For Kat’s venture, meanwhile, Ángel Guerra continues to revise the design. The car will not be stainless.

DeLorean fans have been burned many times by promises of the next car, and given the delays in both projects, skepticism about both potential new ones pervades DeLorean-related internet forums. (Indeed, as this story went to press in April, a San Antonio paper reported that DeLorean Reimagined had shut down its headquarters; a DMC executive told me the company was just moving locations.) Both companies continue to promise big things. Promises, after all, are part of the DeLorean legacy too.

Source : Wired