Solar flares are one of the most powerful phenomena in our solar system. These bursts of radiation sporadically erupt from the Sun and can unleash the energy equivalent of billions of hydrogen bombs in mere minutes.

A better understanding of solar flares can provide valuable insight into the nature of our Sun, as well as how these events can affect Earth. Let’s dive into the basics of solar flares, from what they are to the dangers they can present.

What Is a Solar Flare?

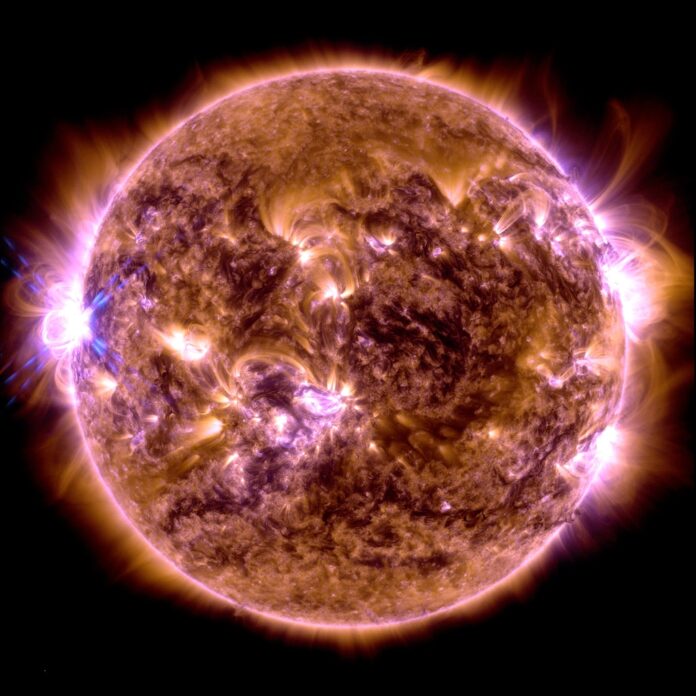

Image captured by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on June 20, 2013 shows the bright light of a solar flare on the left side of the Sun. Credit: NASA/SDO

Solar flares are intense bursts of radiation from the Sun, releasing vast amounts of energy across the electromagnetic spectrum — from radio waves to X-rays to gamma rays. They are caused by the sudden release of magnetic energy stored in the Sun, often near Sunspots, which are areas of concentrated magnetic activity.

When twisted magnetic field lines near sunspots build up enough tension, they can explosively realign, a process called magnetic reconnection. This releases vast amounts of energy, accelerating particles like electrons and protons and heating the surrounding plasma by tens of millions of degrees.

What Causes Solar Flares?

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory captured these images of a solar flare – as seen in the bright flash on the left – on May 5, 2015. Each image shows a different wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light that highlights a different temperature of material on the sun. By comparing different images, scientists can better understand the movement of solar matter and energy during a flare. From left to right, the wavelengths are: visible light, 171 angstroms, 304 angstroms, 193 angstroms and 131 angstroms. Each wavelength has been colorized. (Credit: NASA/GSFC/SDO)

Solar flares are caused by complex interactions between the magnetic field lines that permeate the Sun. These field lines emerge at the solar surface and interact in complicated ways. When magnetic field lines near sunspots get tangled up, they can explosively reconfigure, releasing a burst of energy in the form of a solar flare.

Here’s how solar flares typically occur:

Magnetic Fields

The Sun’s powerful magnetic fields get twisted and tangled up due to the Sun’s differential rotation and the movement of solar plasma.

Energy Buildup and Release

When magnetic field lines near sunspots become too twisted, they snap and realign, releasing a tremendous amount of energy. This process is known as magnetic reconnection.

Radiation Emission

The released energy leads to a solar flare that significantly heats the Sun’s atmosphere, producing radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Particle Acceleration

Solar flares can also accelerate particles like electrons and protons to near-light speeds, leading to further phenomena such as aurorae on Earth.

Read More: How Many Ways Can the Sun Kill Us?

How Do Solar Flares Affect Earth?

An X2.7 class solar flare flashes on the edge of the sun on May 5, 2015. This image was captured by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory and shows a blend of light from the 171 and 131 angstrom wavelengths. The Earth is shown to scale.(Credit: NASA/GSFC/SDO)

Solar flares are so powerful that they often fling large bubbles of superheated plasma out into space, an event called a coronal mass ejection (CME). These plasma clouds are filled with energetic, electrically charged particles, which can interfere with satellite operations, communication systems, and even power grids if they wash over Earth.

For instance, the largest X-class flares have the potential to disrupt GPS and communications satellites, which we depend on every day. And even less powerful flares can pose risks to astronauts due to the hazardous nature of intense radiation.

What Would Happen If a Solar Flare Hit Earth?

The direct hit of a solar flare – or more accurately, the solar storm it produces – can lead to heightened auroras, also known as northern and southern lights. A strong enough flare, particularly an extremely powerful X-class flare, could even cause widespread problems by inducing currents that overload power grids and disrupt communication networks.

One of the most significant examples of a solar storm impacting Earth is the Carrington Event of 1859. At the beginning of September 1859, a powerful geomagnetic storm triggered by a massive solar flare hit Earth with such intensity that it caused telegraph systems across Europe and North America to fail, with reports of operators receiving shocks and telegraph papers catching fire. Though the impact on society at the time was relatively minimal, a similar solar storm today could significantly disrupt our modern, technology-dependent world.

Read More: Our Sun Is Capable of Producing Dangerous ‘Superflares’, New Study Says

When Was the Last Solar Flare?

Solar flares occur frequently, especially during periods of solar maximum, which we are quickly approaching. Significant flares are reported and tracked by space weather monitoring systems like those operated by NASA and NOAA.

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center provides a website that lets users track how space weather may affect Earth. And Spaceweatherlive.com has a webpage that shows recent solar flares based on X-ray data from the Geostationary Operation Environmental Satellite (GOES).

When Is the Next Solar Flare?

Scientists can’t yet accurately predict the exact timing of individual solar flares. However, agencies like NASA and NOAA continuously monitor solar activity to provide forecasts of increased potential for flare activity.

Furthermore, recent research based on data from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) indicates that the Sun’s corona often produces small flashes before regions below are about to experience a solar flare. This potential warning system may eventually help scientists better predict and prepare for flares and the hazardous space weather they can produce.

Understanding solar flares is crucial not only for better understanding our life-sustaining Sun, but also for ensuring our technology-dependent society is protected against potentially hazardous space weather solar flares can create.

Plus, as anyone who has observed a solar flare can attest, they are just darn cool to look at.

Read More: Here’s What Happens to the Solar System When the Sun Dies

Frequently Asked Questions About Solar Flares

Are Solar Flares Dangerous?

Solar flares, particularly X-class flares, can be dangerous, as they can create powerful geomagnetic storms. If these storms strike Earth, they have the potential to damage satellites (and humans) in orbit. And, if they are strong enough, they may even disrupt electrical power grids. Fortunately, Earth’s atmosphere and magnetosphere largely protect people on the ground from the harmful effects of most geomagnetic storms generated by solar flares.

How Often Do Solar Flares Occur?

In general, smaller solar flares occur more often than larger solar flares. The frequency of solar flares also varies with the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle, known as the solar cycle. Solar flares occur more often during solar maximums, and we are currently approaching the peak of solar cycle 25.

How Hot Is a Solar Flare?

The temperature of the Sun’s surface, the photosphere, is “only” about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, or about 6,000 Kelvin. The outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, the corona, is a few million degrees Kelvin. But inside a solar flare, temperatures typically hover between about 10 million and 20 million Kelvin, sometimes climbing as high as 100 million Kelvin.

Can a Solar Flare Destroy Earth?

While solar flares have the potential to significantly disrupt our technological systems, they do not possess nearly enough energy to destroy Earth itself. The main risks of solar flares are to our satellites, power infrastructures, and astronauts.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Jake Parks is a freelance writer and editor who specializes in covering science news. He has previously written for Astronomy magazine, Discover Magazine, The Ohio State University, the University of Wisconson-Madison, and more.

Source : Discovermagazine