Adam Neumann’s bid to buy back WeWork essentially ended this week. A bankruptcy court on Monday approved a deal that gets WeWork out of debt. It could conclude its restructuring and leave bankruptcy by late May following a vote on the deal, thanks to $450 million in financing provided largely by WeWork creditor and real estate technology provider Yardi Systems.

That deal would eliminate $4 billion in debt and also shut the door on Neumann. He’s been persistent in his efforts to buy the company he cofounded but was later forced out of by investors, offering more than $500 million and following up with promises to beat any other offer by 10 percent.

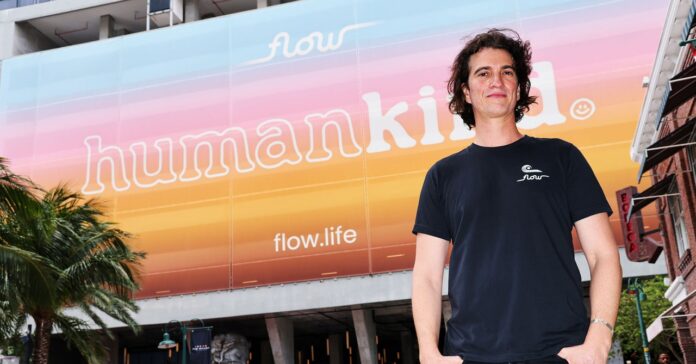

A spokesperson for Neumann did not provide comment about whether he will continue to pursue a purchase of WeWork, or what this meant for the future of Flow, Neumann’s new company that aims to transform the residential rental experience.

“After misleading the court for weeks, WeWork finally admitted it is trying to sell the company to a group led by Yardi for far less than we are continuing to propose, so we anticipate there will be robust objections to confirming this plan,” says Susheel Kirpalani, an attorney for Flow.

WeWork is poised to move past the bid. “Over the past six months, we have worked extremely hard to develop a plan for a reorganized WeWork that is better capitalized, more operationally efficient, and positioned for continued investment in our products and services and a return to long-term growth,” WeWork CEO David Tolley said in a statement announcing the plan.

In 2022, Neumann announced he was working on Flow, and he got $350 million in backing from venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, known as a16z. What exactly the startup would do wasn’t initially clear, but Neumann said it would “elevate” the experience of renting an apartment.

So far, it’s involved rebranding condos, increasing amenities, and adding new building management tech developed by Flow. The company launched Flow buildings in Fort Lauderdale and Miami in April, rebranding existing condos that it previously bought under the Flow name. Available one bedrooms in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, start around $2,500 a month, and from $2,900 in Miami.

Flow owns six buildings in total, including some in Nashville and Atlanta that have not been rebranded as Flow. Bloomberg reported in March that Flow is planning a $300 million development in downtown Miami that would include residential, retail, and work spaces. Neumann had previously tried to venture into housing with WeLive, a co-living idea tied to WeWork, that ultimately failed.

Neumann has said Flow would either “compete or partner” with WeWork as more people work from home. With partnering now looking unlikely, it seems the two may compete.

“Adam can decide to become either a wartime CEO or a peacetime CEO,” says Eric Koester, a professor of innovation and entrepreneurship at Georgetown University. The wartime route would include taking WeWork on and building a competitor of sorts quickly. The peacetime route, Koester says, would rely on differentiating Flow.

He likens Neumann’s situation to when Uber tried to acquire Lyft a decade ago, and Lyft rejected the offer. “Being rejected is something you choose to make personal, or you choose to ignore it,” Koester, a serial entrepreneur, says. Neumann may “take this as a galvanizing force, to say, ‘I’m going to show them,’ or, ‘I didn’t need them anyway, and I’m doing something different.’” Lyft went on to grow and become Uber’s primary, albeit smaller, rival.

Neumann recently described Flow to Business Insider as “an experience-first residential-real-estate company” that leverages tech with a native app and builds community between residents. Flow’s Miami and Fort Lauderdale buildings come as the South Florida region is poised to welcome a glut of flexible living apartments, with several developers building high-rises that allow people to buy furnished condos and either live in them or rent them full-time on Airbnb. The area is a testing ground for branded buildings, and Neumann’s concept for Flow could play into the trend.

When Business Insider asked why Flow, which has a coworking component, needs WeWork, Neumann responded: “Work is part of living, and I don’t know if we need or don’t need anything, but whatever it is that I’m doing, I’m going to do through Flow, and I’ll do whatever is best for Flow.”

Coworking is projected to continue growing, but investing in office real estate still has risks. The Covid-19 pandemic laid those market challenges bare: When offices emptied in 2020, WeWork was left holding the bag. Flow could be vulnerable to similar macroeconomic shifts.

Neumann has touted the tech aspects of Flow, but some are skeptical about whether an apartment building with amenities is a tech company—as with WeWork, whose economic troubles made clear that it was ultimately an office leasing company.

“I think the same question goes with Flow: It’s an apartment building. Is it more than that? That’s a tougher sell,” says Mike Roberto, a professor of management at Bryant University. Flow’s viability and the growth of a vertically integrated living experience will depend on whether or not renters need that. “He’s trying to sell a vision of how we should work and live. At the end of the day, the question isn’t what he thinks our lifestyle should be. It’s: What do people want their lifestyle to be?”

Source : Wired