If all goes well late on May 6, 2024, NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams will blast off into space on Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft. Launching from the Kennedy Space Center, this last crucial test for Starliner will test out the new spacecraft and take the pair to the International Space Station for about a week.

Part of NASA’s commercial crew program, this long-delayed mission will represent the vehicle’s first crewed launch. If successful, it will give NASA – and in the future, space tourists – more options for getting to low Earth orbit.

Suni Williams, right, and Butch Wilmore, the two astronauts who will crew the Starliner test. AP Photo/Terry Renna

From my perspective as a space policy expert, Starliner’s launch represents another significant milestone in the development of the commercial space industry. But the mission’s troubled history also shows just how difficult the path to space can be, even for an experienced company like Boeing.

Origins and Development

Following the retirement of NASA’s space shuttle in 2011, NASA invited commercial space companies to help the agency transport cargo and crew to the International Space Station.

In 2014, NASA selected Boeing and SpaceX to build their respective crew vehicles: Starliner and Dragon.

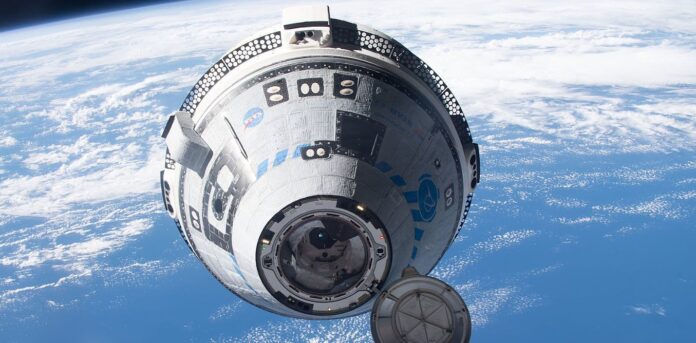

Boeing’s vehicle, Starliner, was built to carry up to seven crew members to and from low Earth orbit. For NASA missions to the International Space Station, it will carry up to four at a time, and it’s designed to remain docked to the station for up to seven months. At 15 feet, the capsule where the crew will sit is slightly bigger than an Apollo command module or a SpaceX Dragon.

Boeing designed Starliner to be partially reusable to reduce the cost of getting to space. Though the Atlas V rocket it will take to space and the service module that supports the craft are both expendable, Starliner’s crew capsule can be reused up to 10 times, with a six-month turnaround. Boeing has built two flightworthy Starliners to date.

The Starliner capsule in transit. AP Photo/John Raoux

Starliner’s development has come with setbacks. Though Boeing received US$4.2 billion from NASA, compared with $2.6 billion for SpaceX, Boeing spent more than $1.5 billion extra in developing the spacecraft.

On Starliner’s first uncrewed test flight in 2019, a series of software and hardware failures prevented it from getting to its planned orbit as well as docking with the International Space Station. After testing out some of its systems, it landed successfully at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

In 2022, after identifying and making more than 80 fixes, Starliner conducted a second uncrewed test flight. This time, the vehicle did successfully dock with the International Space Station and landed six days later in New Mexico.

[embedded content]

The inside of a Starliner holds a few astronauts. Crew members first trained for the launch in a simulator.

Still, Boeing delayed the first crewed launch for Starliner from 2023 to 2024 because of additional problems. One involved Starliner’s parachutes, which help to slow the vehicle as it returns to Earth. Tests found that some links in those parachute lines were weaker than expected, which could have caused them to break. A second problem was the use of flammable tape that could pose a fire hazard.

A major question stemming from these delays concerns why Starliner has been so difficult to develop. For one, NASA officials admitted that it did not provide as much oversight for Starliner as it did for SpaceX’s Dragon because of the agency’s familiarity with Boeing.

And Boeing has experienced several problems recently, most visibly with the safety of its airplanes. Astronaut Butch Wilmore has denied that Starliner’s problems reflect these troubles.

But several of Boeing’s other space activitiesbeyond Starliner have also experienced mechanical failures and budget pressure, including the Space Launch System. This system is planned to be the main rocket for NASA’s Artemis program, which plans to return humans to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo era.

Significance for NASA and Commercial Spaceflight

Given these difficulties, Starliner’s success will be important for Boeing’s future space efforts. Even if SpaceX’s Dragon can successfully transport NASA astronauts to the International Space Station, the agency needs a backup. And that’s where Starliner comes in.

Following the Challenger explosion in 1986 and the Columbia shuttle accident in 2003, NASA retired the space shuttle in 2011. The agency was left with few options to get astronauts to and from space. Having a second commercial crew vehicle provider means that NASA will not have to depend on one company or vehicle for space launches as it previously had to.

Perhaps more importantly, if Starliner is successful, it could compete with SpaceX. Though there’s no crushing demand for space tourism right now, and Boeing has no plans to market Starliner for tourism anytime soon, competition is important in any market to drive down costs and increase innovation.

More such competition is likely coming. Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser is planning to launch later this year to transport cargo for NASA to the International Space Station. A crewed version of the space plane is also being developed for the next round of NASA’s commercial crew program. Blue Origin is working with NASA in this latest round of commercial crew contracts and developing a lunar lander for the Artemis program.

SpaceX’s dragon capsule. NASA TV via AP

Though SpaceX has made commercial spaceflight look relatively easy, Boeing’s rocky experience with Starliner shows just how hard spaceflight continues to be, even for an experienced company.

Starliner is important not just for NASA and Boeing, but to demonstrate that more than one company can find success in the commercial space industry. A successful launch would also give NASA more confidence in the industry’s ability to support operations in Earth’s orbit while the agency focuses on future missions to the Moon and beyond.

Wendy Whitman Cobb is a Professor of Strategy and Security Studies at Air University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source : Discovermagazine