An ion might be to blame for an almost dry and devoid-of-water Venus. The planet, the second from the sun, is the hottest in the solar system. Its thick atmosphere holds in so much heat, and the surface is blazing enough to melt lead.

But at one point, Venus might have been similar to Earth, a planet with lots of water. A new study published in Nature, found that hydrogen atoms in Venus’ atmosphere, needed for water, may have escaped to space.

The find, simulated with computer modeling, might explain what happens to liquid water across the universe.

“Water is really important for life,” said Eryn Cangi, co-author and a research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, in a press release. “We need to understand the conditions that support liquid water in the universe, and that may have produced the very dry state of Venus today.”

Losing Water on Venus

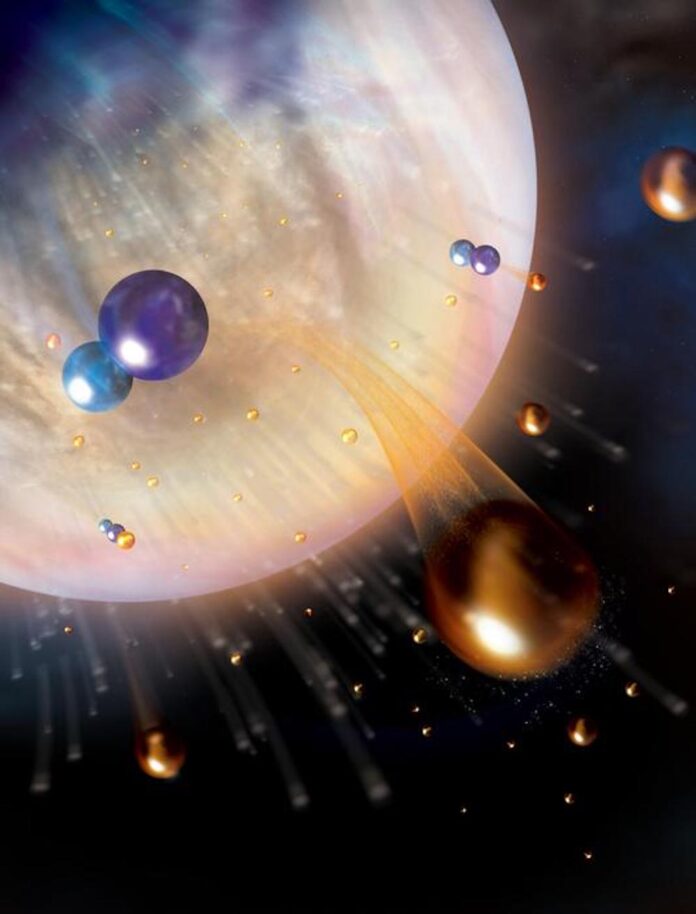

At one point, Venus might have hosted seas like Earth. So, what happened? The study’s scientists suspect that Venus underwent a powerful greenhouse event that raised temperatures to 900 degrees Fahrenheit. After this happened, all the planet’s water evaporated, leaving some droplets behind. Even the few drops that were left over might have vanished because of an ion, HCO+, in the planet’s atmosphere.

This type of molecule forms when water mixes with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. HCO+ might also be the reason why Mars is dry and losing its water.

The ion is produced in the atmosphere on Venus but doesn’t stay there long. Electrons found in the atmosphere recombine HCO+ ions to split them in two. When this happens, hydrogen ions escape into space, leaving Venus without the hydrogen, one of the two compounds needed for water. The phenomenon is called “dissociative recombination” and might cause Venus to lose twice as much water daily.

While the team suspects this is the reason for Venus’s dryness, HCO+ has never been observed on the planet. The study’s researchers want to send probes and tools that can detect this ion.

“One of the surprising conclusions of this work is that HCO+ should actually be among the most abundant ions in the Venus atmosphere,” said Michael Chaffin, study co-author and a researcher at Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, in a statement.

Read More: The Curious Question of Life on Venus

Future Venus Missions

(Credit: NASA GSFC visualization by CI Labs Michael Lentz and others)

Other missions to Venus are set to probe the atmosphere for signs if it was ever habitable. For example, NASA’s Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (DAVINCI) mission will map the planet and probe the clouds. The mission is scheduled to launch in the 2030s. The spacecraft also won’t probe for HCO+ specifically, but it will still be vital in understanding the history of water on Venus.

“There haven’t been many missions to Venus,” Cangi said in a press release. “But newly planned missions will leverage decades of collective experience and a flourishing interest in Venus to explore the extremes of planetary atmospheres, evolution, and habitability.”

Read More: Life in the Clouds of Venus? Maybe Not.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Elizabeth Gamillo is a staff writer for Discover and Astronomy. She has written for Science magazine as their 2018 AAAS Diverse Voices in Science Journalism Intern and was a daily contributor for Smithsonian. She is a graduate student in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing.

Source : Discovermagazine