Cryptocurrency has always made a ripe target for theft—and not just hacking, but the old-fashioned, up-close-and-personal kind, too. Given that it can be irreversibly transferred in seconds with little more than a password, it’s perhaps no surprise that thieves have occasionally sought to steal crypto in home-invasion burglaries and even kidnappings. But rarely do those thieves leave a trail of violence in their wake as disturbing as that of one recent, ruthless, and particularly prolific gang of crypto extortionists.

The United States Justice Department earlier this week announced the conviction of Remy Ra St. Felix, a 24-year-old Florida man who led a group of men behind a violent crime spree designed to compel victims to hand over access to their cryptocurrency savings. That announcement and the criminal complaint laying out charges against St. Felix focused largely on a single theft of cryptocurrency from an elderly North Carolina couple, whose home St. Felix and one of his accomplices broke into before physically assaulting the two victims—both in their seventies—and forcing them to transfer more than $150,000 in Bitcoin and Ether to the thieves’ crypto wallets.

In fact, that six-figure sum appears to have been the gang’s only confirmed haul from its physical crypto thefts—although the burglars and their associates made millions in total, mostly through more traditional crypto hacking as well as stealing other assets. A deeper look into court documents from the St. Felix case, however, reveals that the relatively small profit St. Felix’s gang made from its burglaries doesn’t capture the full scope of the harm they inflicted: In total, those court filings and DOJ officials describe how more than a dozen convicted and alleged members of the crypto-focused gang broke into the homes of 11 victims, carrying out a brutal spree of armed robberies, death threats, beatings, torture sessions, and even one kidnapping in a campaign that spanned four US states.

In court documents, prosecutors say the men—working in pairs or small teams—threatened to cut toes or genitalia off of one victim, kidnapped and discussed killing another, and planned to threaten another victim’s child as leverage. Prosecutors also describe disturbing torture tactics: how the men inserted sharp objects under one victim’s fingernails and burned another with a hot iron, all in an effort to coerce their targets to hand over the devices and passwords necessary to transfer their crypto holdings.

“The victims in this case suffered a horrible, painful experience that no citizen should have to endure,” Sandra Hairston, a US attorney for the Middle District of North Carolina who prosecuted St. Felix’s case, wrote in the Justice Department’s announcement of St. Felix’s conviction. “The defendant and his coconspirators acted purely out of greed and callously terrorized those they targeted.”

The serial extortion spree is almost certainly the worst of its kind ever to be prosecuted in the US, says Jameson Lopp, the cofounder and chief security officer of Casa, a cryptocurrency-focused physical security firm, who has tracked physical attacks designed to steal cryptocurrency going back as far as 2014. “As far as I’m aware, this is the first case where it was confirmed that the same group of people went around and basically carried out home invasions on a variety of different victims,” Lopp says.

Lopp notes, nonetheless, that this kind of crime spree is more than a one-off. He has learned of other similar attempts at physical theft of cryptocurrency in just the past month that have escaped public reporting—he says the victims in those cases asked him not to share details—and suggests that in-person crypto extortion may be on the rise as thieves realize the attraction of crypto as a highly valuable and instantly transportable target for theft. “Crypto, as this highly liquid bearer asset, completely changes the incentives of doing something like a home invasion,” Lopp says, “or even kidnapping and extortion and ransom.”

Three Failed, Brutal Crypto Extortions

Despite the potential of stealing crypto through that kind of physical coercion, St. Felix’s gang had remarkably little success extorting significant sums of cryptocurrency from victims. But it wasn’t for lack of trying: One document written by prosecutors, which outlines the basis for a plea agreement for one of the gang’s lookout drivers, describes how the group began to form in 2021 and went on to carry out a series of brutal attacks involving 13 total members of the gang over the next two years in at least seven actual or planned operations in Florida, Texas, North Carolina, and New York, all targeting victims they believed to have large stashes of crypto.

The group’s string of crypto burglaries had its origins, in fact, in more traditional hacking-based crypto theft. According to prosecutors, one member of the group, Jarod Seemungal, and several alleged associates he’d met via the online game Minecraft, began in late 2020 to carry out so-called SIM swaps—in which hackers trick a phone company into transferring a victim’s phone’s service to their own device and then steal their two-factor authentication codes—to gain access to victims’ online accounts and siphon out their crypto funds. Prosecutors say Seemungal’s crew carried out multiple SIM swaps, prosecutors write, including one case in which they stole more than $3 million from a single victim.

By 2022, however, Seemungal’s gang had begun to consider expanding their tactics to a far more violent form of crypto theft in order to hit targets who couldn’t easily be robbed via hacking. He approached three members of what would eventually become the wider burglary group—St. Felix as well as two other young men in South Florida. St. Felix then went on to recruit most of the rest of the dozen-plus accomplices, all of whom coordinated their crimes on the messaging service Telegram.

In their first break-in, according to the prosecution’s plea document, the group targeted the same victim from whom Seemungal had already stolen more than $3 million via SIM swapping, seeking to steal another $500,000 in crypto that she had managed to retain. At 11:30 pm on September 12, 2022, St. Felix and at least one other member of the group, wearing masks and armed with handguns and a rifle, broke into the woman’s living room by shattering a sliding glass door. After struggling with the victim and another member of her household who suffered from Parkinson’s disease, they put the woman on her knees, held a gun to her head, and demanded the password to an account on the Gemini crypto exchange.

She refused to give up her password, and was, according to the prosecutors’ description, so demoralized by the earlier hacking theft of the majority of her funds that she told the men to simply shoot her. Instead, they stole her engagement ring, two iPhones, a laptop, the charger for the neurostimulator used by the other member of the household as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease, and whatever cash they could find, then left.

For their next victim, the prosecutors describe how the group targeted a man who Seemungal knew to be a fellow SIM swapping hacker and who he believed had in fact robbed him of a significant sum of cryptocurrency in 2021. To prepare for that robbery in September of 2022, they began repeatedly sending their target pizza deliveries in the hope of conditioning him to come to his door without suspicion. When the moment of their planned theft came, however, their target wasn’t home, so they instead lay in wait, then drew guns on their target when he arrived at the house.

Over the next hour, the group bound their victim’s hands behind his back with bootlaces and demanded he hand over access to his crypto accounts. When the account he gave them access to had only a small sum of crypto, they put him in the backseat of their rented Cadillac, struck his face with their guns, drove away, and began extorting his friends and father for crypto payments. Eventually, about 120 miles from their victim’s home, the men took their victim out of the car and told him to kneel. He instead escaped, as one of the men fired a gun from the moving car, though it’s not clear if the shot was intended to hit the victim or merely scare him. One of the group—who has not yet been charged—would later say that St. Felix had suggested they kill their captive.

A few months later, prosecutors write, the group carried out their next attack against another victim they believed to be a wealthy crypto-focused hacker, this time in Texas. On a road trip from Florida to start surveilling their target, St. Felix had fled from law enforcement in Louisiana, flipped his car at more than 90 miles per hour, and broken his leg. The other members of the Florida crew had been arrested after that crash. So the break-in was carried out by a newly recruited team based in the Houston area.

Just a few days before Christmas of 2022, the Texas group broke into their target’s home, bound his family members’ hands with zip ties, and repeatedly hit him in the face demanding he give them access to his cryptocurrency. Prosecutors say they shoved knives and forks under his mother’s fingernails and struck her in the face with a gun. They burned their target’s arm with a hot iron to coerce him to hand over his crypto account details, and at one point attempted to punch him in the genitals.

The victim eventually told his torturers that he had buried a device storing his cryptocurrency in the backyard. (In fact, that hardware wallet, holding $1.4 million in crypto, was in a moving box in the home that the thieves never found.) When the thieves brought their victim to the backyard to locate the device, he climbed a fence and escaped. The burglars stole $150,000 in cash as well as some jewelry, then left.

One Final Job

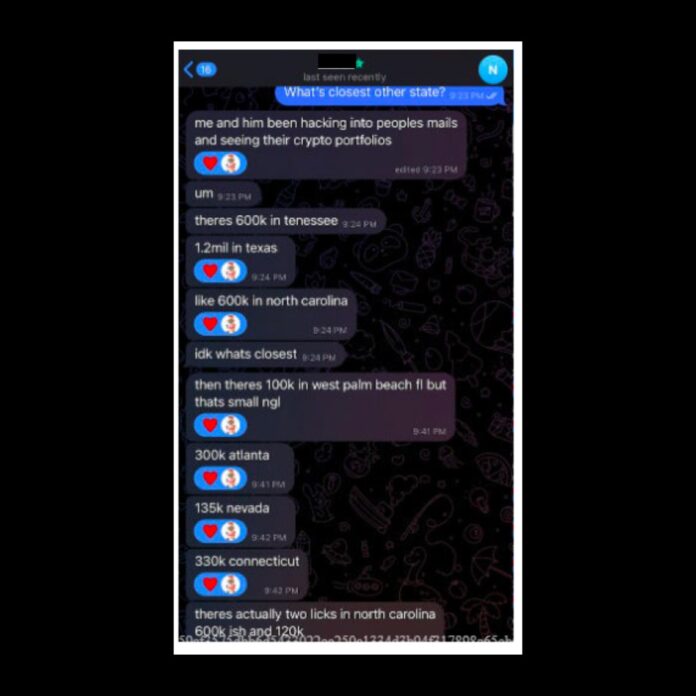

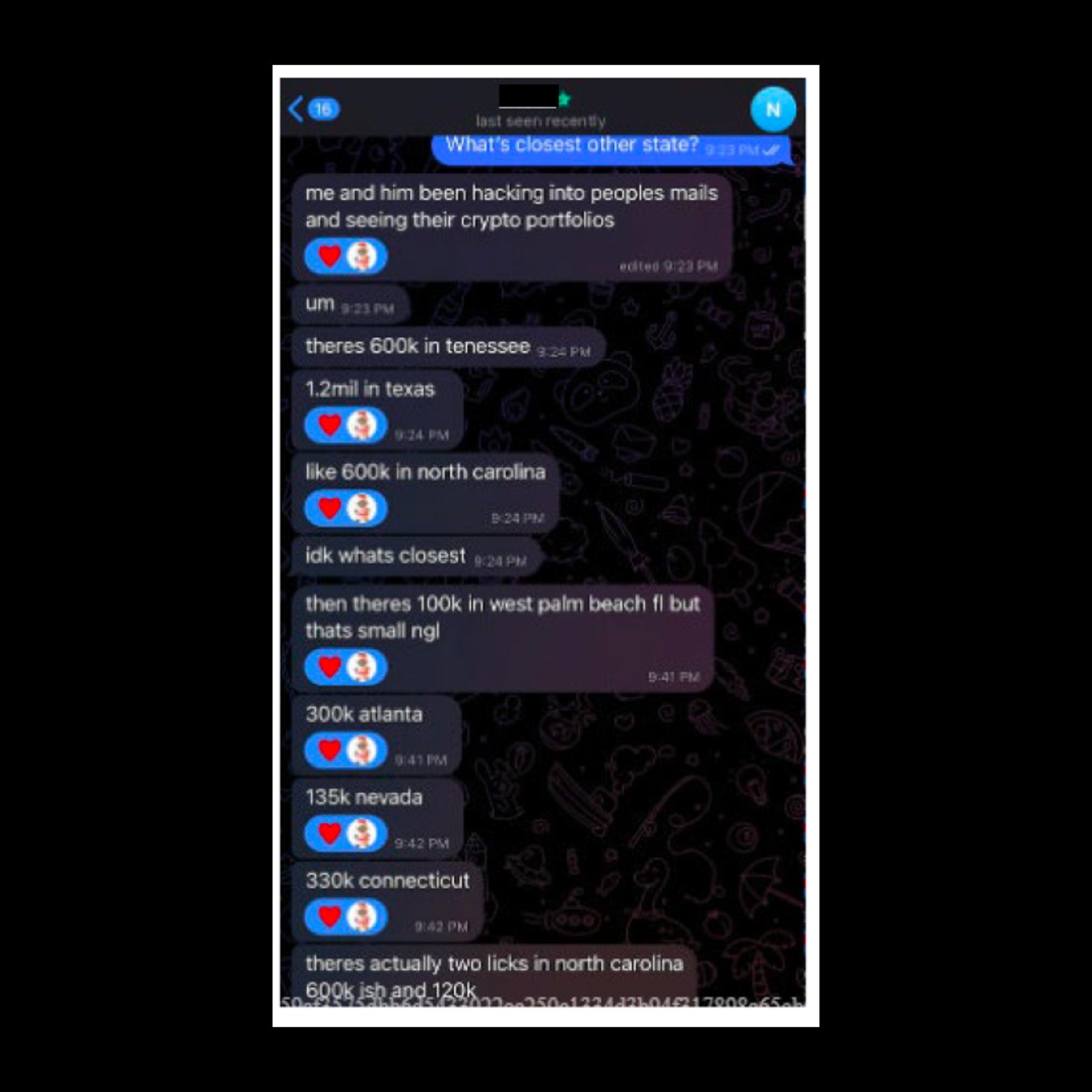

In early 2023, after those relatively unsuccessful attempts at extortion, an associate of Seemungal’s allegedly began feeding the group tips, hacking into potential targets’ email to see the size of their crypto holdings, and sending those leads to the home invasion crew. One Telegram chat obtained by prosecutors shows a discussion of potential targets, including someone with $1.2 million in Texas and another person with $600,000 in Tennessee.

They decided to go after a “new targ in north carolina” that they described as “some old dude”—a crypto investor in his seventies. In April, St. Felix and his crew drove to Durham, North Carolina, and knocked on the victim’s door at 7:30 am, dressed as construction workers. When his wife came to the door, they knocked her to the floor. When the elderly man heard his wife scream and entered the room, they punched him in the face, bound the couple with zip ties, and dragged his wife into a bathroom.

During the rest of their time in the couple’s home, they coerced the man to give them access to his crypto holdings by threatening to cut off his toes and genitalia, to sexually assault his wife, and to shoot him. The man eventually transferred about $156,000 worth of crypto from his Coinbase exchange account to his captors before Coinbase began to block his transactions. The thieves then destroyed their victims’ computers and phones, left them bound with zip ties in the bathroom, and escaped.

That extortion incident would be the group’s last, according to the prosecutors. On another occasion, they broke into a would-be victim’s home only to discover it was an empty rental property. St. Felix and Seemungal were still planning more attacks in July of 2023 when St. Felix was arrested in the parking lot of a McDonald’s in West Hempstead, New York, with an AK-style rifle and zip ties in his vehicle. According to the group’s communications, they had discussed another target in Orlando, Florida, and yet another in Long Island, New York. For that final victim, the group had hacked the target’s email, and St. Felix had suggested using one of the person’s three children for leverage.

Should Have Stuck to Hacking

The criminal complaint against St. Felix suggests that identifying him as the ringleader of the crypto-focused home invasion crew wasn’t particularly hard. Cell tower records placed his phone at the location of the Durham break-in. Bank records show his checking account purchases from Walmart of the construction worker outfit he would wear during the robbery. Google cloud storage records show screenshots of the reconnaissance he carried out in targeting his Durham victim.

The FBI’s analysis of St. Felix’s cryptocurrency transactions found that he used the instant exchanger FixedFloat to swap bitcoin and ethereum stolen from the North Carolina man for Monero, a cryptocurrency designed to be difficult to trace, and then back to ethereum. But because he carried out those swaps in a single web session, prosecutors were able to subpoena FixedFloat for its records and show that the sender and recipient were almost certainly the same person, despite his attempts at obfuscation. “FixedFloat basically connected the beginning and end points of the tunnel,” says Chris Janczewski, head of global investigations at cryptocurrency tracing firm TRM Labs, which published an analysis of the case. “It doesn’t matter what you do in between if you can connect the inputs and outputs.”

Overall, the risk-reward trade-offs of carrying out brutal home invasions like the ones in St. Felix’s case don’t make nearly as much sense as remote hacking for crypto theft, Janczewski points out, although both tactics are highly illegal and potentially ruinous for victims. St. Felix and his coconspirators made a relatively small amount of money in the long run, carried out highly risky physical intrusions, and now face years in prison. St. Felix himself, for instance, faces a mandatory minimum of seven years and a maximum of a life sentence.

Still, crypto holders should nonetheless beware of the apparent rise in physical coercion as a means to steal their funds, says Casa’s chief security officer, Jameson Lopp. He offers tips for protecting yourself against those attacks that include maintaining privacy—thieves won’t go after a crypto stash they don’t know about or can’t physically locate—and creating technical hurdles to quickly sending large sums of crypto, even for yourself.

“If you can spend millions of dollars in a few seconds or a few minutes, then that’s a pretty good indication you probably don’t have enough layers of security around those assets,” Lopp says.

Cryptocurrency’s appeal, of course, has long included that it allows instant, frictionless transfers of vast amounts of wealth. Any crypto holder unlucky enough to be faced with a threat to their life or their loved ones, however, may quickly find themselves wishing for a form of money that didn’t hold the same appeal to the very dangerous person putting a gun to their head.

Source : Wired