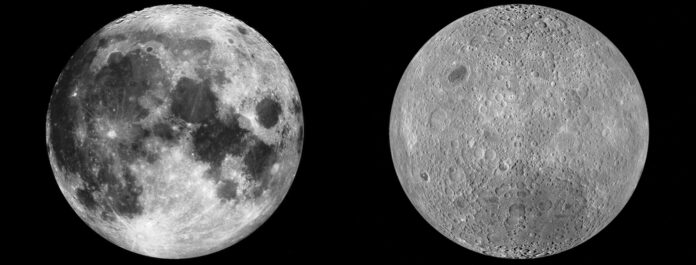

The far side of the moon has been shrouded in mystery for years, and questions have piled up about its differences from the near side, which we see nearly every night here on Earth.

In a push to ascertain the moon’s uncharted secrets, progress on exploring the far side has accelerated in recent years. In early June 2024, China made the news as its newest space probe, Chang’e 6, landed on the moon’s far side, marking a bold direction for future lunar exploration.

What Is the Chang’e 6 Mission?

China launched the Chang’e 6 probe on May 3, 2024 with the intent of collecting samples of lunar regolith (a surface layer of dust, sand, and rock fragments) on the moon’s far side. A similar mission occurred in 2020, when China’s Chang’e 5 probe retrieved samples from Oceanus Procellarum — the largest of the lunar maria, which are basaltic plains mostly on the moon’s near side that were formed by lava flows.

In 2019, China became the first country — and so far, the only country — to have a successful landing on the far side of the moon with its Chang’e 4 mission, which dispatched a landing platform and a rover named Yutu-2. The lander and rover arrived at the Von Kármán crater in the southern hemisphere of the far side and have since accomplished multiple objectives, such as measuring radiation levels and studying regolith.

After landing in the southern mare of the Apollo Basin earlier this month, the Chang’e 6 probe used a robotic drill and arm to obtain samples. The samples were then transferred to a module in lunar orbit, which successfully returned to Earth on June 25, 2024 landing in Inner Mongolia. The delivered material will now undergo studies in an attempt to reveal the history of the far side’s unfamiliar features.

Read More: First Results From the Moon’s Far Side

Before the Chang’e missions, the lunar far side had not been explored because of difficulties related to communication and navigating the terrain, which contains an abundance of craters and far less maria than the near side.

The far side was first seen in 1959 when the Soviet Union’s Luna 3 spacecraft captured several low resolution images of it. In 1962, NASA’s Ranger 4 spacecraft crash-landed on the far side, although it still holds the title of the first U.S. spacecraft to reach another celestial body.

With renewed interest in lunar exploration from multiple nations and private companies eager to roll out more missions, the far side may start to become a more appealing destination.

The main reason for this is strategic long-term development, at least for world powers like China and the U.S.: Water ice deposits in lunar soil, which could be used for drinking or fuel generation, could give nations the green light for base construction near the lunar south pole. Russia and a handful of other nations have joined China to plan the creation of a proposed lunar base called the International Lunar Research Station.

The U.S. has set its sights on moon exploration with the Artemis program, started in 2017. One of the program’s goals is to build the Lunar Gateway space station, a research and communication center that is planned to launch in 2027 and will be located in orbit near the moon. The project will feature collaboration with the European Space Agency and several other space programs.

Read More: Artemis Prepares to Take People to the Moon and Beyond

Research on the Far Side

NASA is also supporting aerospace companies that will be sending experiments and technologies to the far side through its Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative. One company is Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Draper Laboratory, which plans to land near Schrödinger Basin on the lunar south pole in 2025, anticipated to be the first U.S. landing on the far side.

The Draper lander will deliver three science payloads that will monitor seismic activity, the moon’s magnetic field, and heat flow and electrical conductivity underneath the lunar surface.

Another upcoming mission that NASA supports is Texas-based company Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Mission 2, expected to land on the far side in 2026. The mission will transport several payloads, including NASA’s LuSEE-Night radio telescope; LuSEE-Night will take advantage of a significant characteristic of the far side: its radio silence.

Read More: 15 of the Most Life-Changing Spacecraft and Missions That Fueled Our Curiosity

A Quiet Zone and New Space Race

The far side is considered a radio-quiet zone, meaning it is shielded from radio emissions that originate on Earth. This makes it a critical location to study radio signals that may give researchers a glimpse into space’s early history.

A call to maintain radio silence in this area of the moon has been growing due to concerns that it may soon experience interference from an influx of radio-wave emitting orbiters and landers. In March 2023, the topic was front and center at the first Moon Farside Protection Symposium, held by the International Academy of Astronautics.

In the coming years, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program will continue with missions to the moon. Chang’e 7 is expected to launch in 2026 to assess potential deposits of water ice on the moon’s south pole. It will be followed by Chang’e 8 in 2028, a mission that will complete further testing to prepare for the eventual construction of a lunar base.

With the far side continuing to attract interest, some have cited the surge in planned space missions as a sign that a new space race is underway. During the next decade, there are sure to be exciting scientific advancements that will enhance researchers’ understanding of the moon and its secrets.

Read More: Here Are 4 Reasons Why We Are Still Going to the Moon

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Jack Knudson is an assistant editor at Discover with a strong interest in environmental science and history. Before joining Discover in 2023, he studied journalism at the Scripps College of Communication at Ohio University and previously interned at Recycling Today magazine.

Source : Discovermagazine