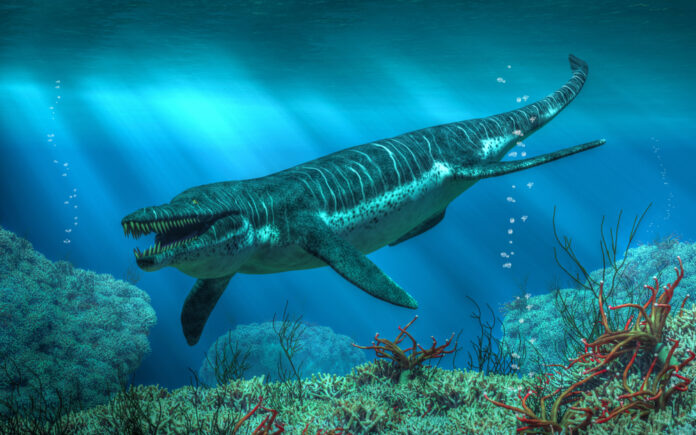

The Kronosaurus was a massive marine predator with a fearsome jaw, big enough to swallow an adult human whole. They had huge teeth — about 12 inches long from the base to the tip, which they used to eat almost anything they could get their teeth on during the Early Cretaceous.

“In terms of size, they are some of the biggest,” says Leslie Noe, a paleontologist at the University of the Andes in Bogota, Colombia.

And the fearsome jaw is all we know about the Kronosaurus queenslandicus — the only species that nearly everyone agrees is a Kronosaurus. Much of the rest of the genus of large pliosaurs, that were formerly considered Kronosaurs, have since been reassigned to other branches of the large, short-necked pliosaur family.

The Kronosaurus Discovery

Albert Heber Longman described the K. queenslandicus in 1924 and named it after Queensland, the Australian state where his predecessor had originally discovered the species decades earlier. The “Kronos” part of the moniker referred to the titan of Greek legend, Cronus.

A piece of the lower jaw was the only discovery at that time, which while it was massive, it wasn’t a good holotype to build a whole new genus from, Noe says. Still, based on the finding and by comparing it with similar types of marine predators, researchers estimated the animal reached a length of about 12 meters.

Longman considered Kronosaurus a pliosaur — a group of large marine predators with powerful jaws and four large fins.

Read More: 5 of the Most Interesting Prehistoric Marine Reptiles

Prey and Predators of the Kronosaurus

In the Early Cretaceous, with a powerful jaw, K. queenslandicus fed on other big marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, along with large ammonites.

“They probably could have eaten just about anything,” Noe says. “I suspect if you’re that big, you’re not that bothered if you’re hungry.”

Another study published in 2009 found that these creatures likely had a massive bite force — about the same as a saltwater crocodile.

Given their size, Noe speculates that pregnant females also gave live birth, since they were likely too big — and their flippers too small — for them to drag themselves onto land to lay eggs.

It’s possible that their young were preyed on themselves by other large pliosaurs, plesiosaurs or ichthyosaurs, like the way orcas today prey on the young of larger whales.

“The biggest threat would have probably been another pliosaur,” Noe says.

Read More: 6 Ancient Mega-Predators that Once Ruled the World

A Hot Debate

In subsequent years after K. queenslandicus was described, several other specimens were described as belonging to the Kronosaurus genus. But the taxonomy of this whole group has been up for debate.

When a specimen was discovered in the 1970s, it was initially described as Kronosaurus boyacensis.

“It was big, and from the southern continent, so assumed to be Kronosaurus,” Noe said.

But more recently, Noe and a colleague redescribed the specimen as Monquirasaurus boyacensis since the characteristics of the Colombian fossil didn’t match the original Australian Kronosaurus holotype.

Harvard University scientists in Australia described another fossil as a Kronosaurus in the 1930s. Noe and other researchers have doubts that this specimen belongs to Kronosaurus, but restoration has covered up some of the defining features of this specimen making it difficult to know for sure. There are other fossils in Australia that may not belong either, Noe says, due to differences in ages.

As far as Noe is concerned, the Kronosaurus taxonomy is still up in the air. The original bones that Longman described don’t have enough defining characteristics to say for certain, but most of the other subsequent specimens categorized as Kronosaurus don’t seem to match with K. queenslandicus.

“They are really, really big and difficult to study,” Noe says about large pliosaurs.

Read More: Why Were Prehistoric Marine Reptiles So Huge?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Joshua Rapp Learn is an award-winning D.C.-based science writer. An expat Albertan, he contributes to a number of science publications like National Geographic, The New York Times, The Guardian, New Scientist, Hakai, and others.

Source : Discovermagazine