We’ve known for awhile that 2023 was by far the warmest year on record, triggering widespread alarm among climate scientists. Now, a newly released climate report reveals other disturbing trends.

No aspect of Earth’s climatic life support system was spared from humankind’s impact last year, according to the State of the Climate 2023 report, led by scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

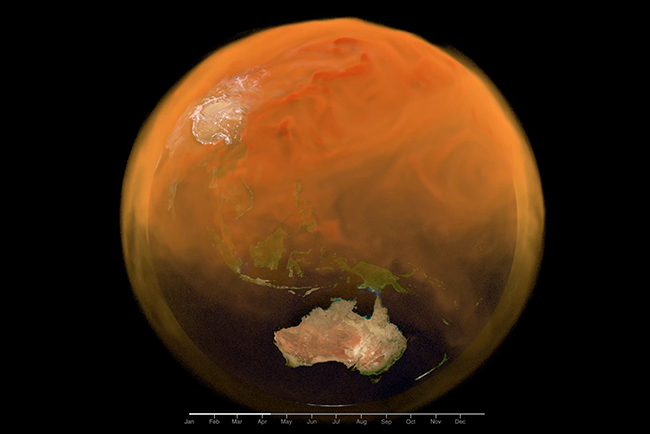

Driving it all was an accelerating build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, triggering record-setting temperatures on land and at sea. Other shifts included dissipating cloudiness, paltry precipitation (but also devastating deluges), expanding drought, record-setting wildfires, shriveling glaciers and ice sheets, and rising sea level.

“This report documents and shares a startling, but well established picture: We are experiencing a warming world as I speak, and the indicators and impacts are seen throughout the planet,” said Deke Arndt, director of NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. “The report is another signpost to current and future generations.”

In this column, and in two others to follow, I’ll summarize the most salient findings of the report. Here in Part 1, I focus on rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. In Part 2, I’ll focus on just how rapidly this has driven up temperatures on land and at sea. And in Part 3, I’ll describe other disturbing climate impacts detailed in the report, some of which you may find surprising.

Faster and Faster Down a Perilous Path

In 2023, “Earth’s major greenhouse gases — carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide — all increased to new record highs,” according to the report. The globally averaged concentration of carbon dioxide, the most important and abundant of the three, reached just over 419 parts per million. That’s 50 percent greater than in pre-industrial times.

This graphic shows the daily average levels of CO2 in the atmosphere between 2014 and the present, as measured at four observatories: Barrow, Alaska (in blue), Mauna Loa, Hawaii (in red), American Samoa (in green), and South Pole, Antarctica (in yellow). CO2 levels vary naturally on a seasonal basis, as revealed by the up and down signals. The black lines show global averages based on measurements from the four sites, with the curving line showing the seasonal cycle and the straight one portraying the long-term trend with the seasonal cycle removed. (Credit: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory)

Even more unsettling, we’ve been accelerating in the wrong direction. Carbon dioxide’s rate of annual growth in the atmosphere during the last decade was more than four times greater than it was in the early 1960s.

The main culprit is increased fossil fuel burning to meet humankind’s rising demand for energy. Three times more CO2 is now billowing into the atmosphere from this activity than during the 1960s, the report found.

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas, and in 2023 its concentration in the atmosphere reached a little more than two and a half times its pre-industrial level. Human activities pour methane into the atmosphere in a number of ways, including extraction of fossil fuels, raising of livestock, dumping of waste in landfills, and cultivation of rice. But there are natural sources as well, including wetlands and shallow lakes.

The main drivers of rising methane in the atmosphere now appear to be increasing emissions from livestock as well as from natural wetlands and lakes. And one disturbing prospect raised by the report’s authors is that more methane is pouring from tropical wetlands in response to a warming climate — possibly “an indication of an emerging climate feedback.”

Climate scientists have for years been concerned about the response of wetlands to climate change. That’s because warmer temperatures can cause activity by methane-producing microbes living in these low-oxygen environments to increase.

If this is indeed happening, it would mean rising methane from wetlands is helping drive temperatures higher, which is causing more methane to be released from the wetlands, which is raising temperatures even higher — all in a dangerous, self-reinforcing feedback loop.

“We are definitely not on the right path to limit global warming,” said Xin Lindsay Lan, a carbon-cycle scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory who led the report’s analysis of greenhouse gases. “The planet is already warming rapidly, so it’s a critical time to reduce those greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere. Instead, we are seeing a rapid increase.” (In the interest of full disclosure, Lan also is affiliated with the University of Colorado, where I direct the Center for Environmental Journalism.)

She notes that there have been many efforts to cut emissions globally. Among them is the far-reaching Inflation Reduction Act in the United States. And these efforts have blazed a promising trail forward by showing that it’s possible to bring emissions down without smothering economic activity.

In fact, last year CO2 emissions from advanced economies like the United States actually fell 4.5 percent — a record decline outside of a recessionary period. According to a report from the International Energy Agency, this occurred even as gross domestic product jumped by 1.7 percent. Emissions from these economies fell by 520 million tons last year, taking them back to their level of 50 years ago, according to the IEA.

But at the same time, large increases in emissions from other countries in 2023, combined with declines in production of electricity from hydropower due to drought, greatly offset the strides made by others. For example, China’s emissions of carbon dioxide grew by about 565 megatons in 2023. That was “by far the largest increase globally and a continuation of China’s emissions-intensive economic growth in the post-pandemic period,” according to the IEA report.

The IEA report is very much consistent with what the State of the Climate 2023 analysis has found. As Lan puts it, “our data show that global greenhouse gas concentrations remain at very high levels. If emissions had decreased significantly, we would have seen a slowdown in the rise of global CO2 levels, but there’s no evidence of that. In fact, the increase in CO2 from 2022 to 2023 was the fourth largest in recorded history.”

The bottom line is this: Despite very hopeful strides forward, the world has so far fallen far short of what’s necessary to restrain the growth in atmospheric greenhouse gases, let alone begin to bring the levels down quickly so that we can preserve a decent climate for our children and grandchildren.

For Part 2 of this series, please go here. And for Part 3, click here.

Source : Discovermagazine