On a bright day overlooking Beverly Hills, Al Pacino recalls a warning from years ago, from his therapist: “He said, ‘Don’t go to L.A., Al!'”

But here is, and even now, at 84, he’s still adjusting to that Hollywood life.

“You have to learn how famous you are,” he said.

Has he? “What, now? I’m trying!” he laughed. “What do you want from me? I actually put a tie on to see you. That’s what famous guys do!”

He’s more than “famous.” He’s Al Pacino, with nine Oscar nominations, seven straight without a win, until “Scent of a Woman.” Plus, two Emmys, two Tonys, a Kennedy Center Honor, and a life achievement award from the American Film Institute. He’s been a leading man in the movies, and a character actor, for nearly 55 years.

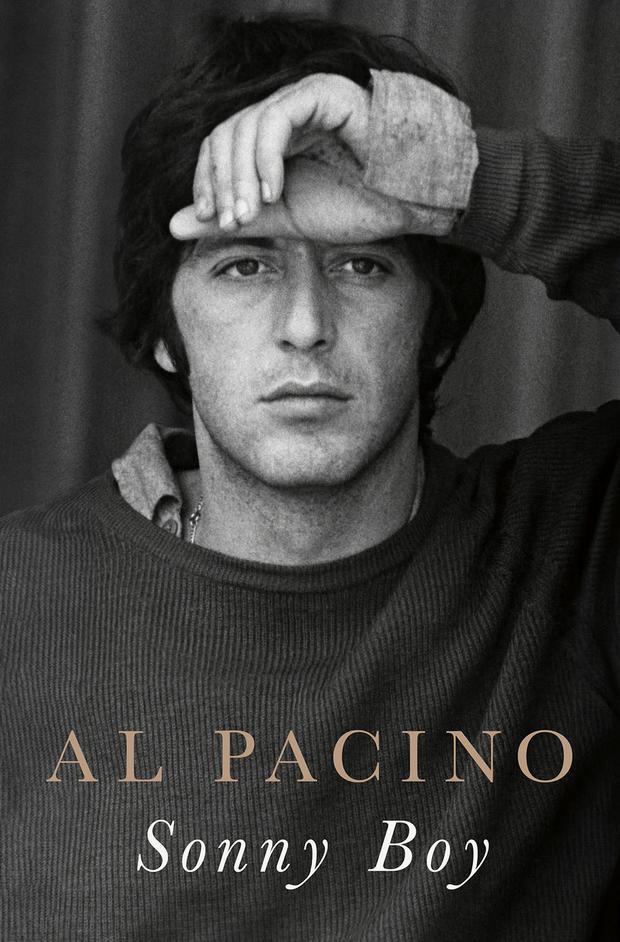

“I’m an old fella, you know?” he laughed. “When I have my hair now and I go out and someone takes a picture of me, all you see is, like, a white hydrant! A white fire hydrant! I don’t feel I’m gray yet. I don’t want to be gray. I’m that guy in the book cover.”

That guy on the book cover is finally telling his own story. It’s in his new memoir, “Sonny Boy.” That’s what his mom, Rose, called him.

They lived with Al’s grandparents in a three-room walk-up in the South Bronx. Rose kept her Sonny Boy in when his friends tempted him with the streets.

Pacino recalled that when his buddies would call for him to go out, on a school night, “She said, ‘No, no.’ And I was so upset. So angry at her. I think she was part of what saved my life, and kept me off drugs. I couldn’t go out. I went to school.”

If his mother saved his life, another woman changed it. “Blanche Rothstein, who was my eighth grade teacher, actually came to my apartment, and she sat down and talked to my grandmother,” he said. “What she said, I don’t know, but I think it finally came down to, ‘You should encourage this boy to do what he’s doing, the acting. You have to. He is made to do this.'”

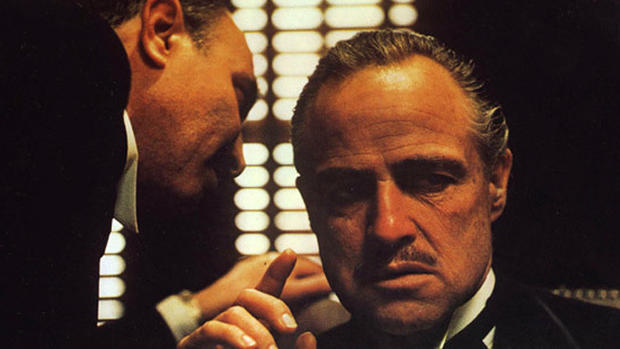

Good reviews came very early – at 13, after a school show, a stranger came up to him and said, ‘You’re the next Marlon Brando.” Al’s response? “Who’s Marlon Brando?”

At 16, Pacino dropped out of school to immerse himself in the New York theater scene. To survive, he took any job: messenger, janitor, switchboard operator, twice an usher, twice fired.

Pacino said, “I was in this Carnegie Hall place …”

“This ‘Carnegie Hall place’?” asked Mankiewicz. “It’s Carnegie Hall!”

“It’s … Carnegie Hall. I had this tuxedo on and they liked – you know, I was relatively good-looking. So, there were these people coming in, and I’m supposed to seat them.”

“It’s the job of an usher, Al.”

“It is the job an usher!” Pacino laughed. “Finally. But I didn’t last doing that. I just didn’t have the heart to do it. I said, ‘Sit anywhere you want.’ I mean, you got a better seat if you’re up further than when you’re down. And then there was a fist fight. And on the spot, I was gone.”

Thankfully, Pacino had the stage, where he made a name for himself, and got the attention of a young director, Francis Ford Coppola, who saw him as Michael Corleone in “The Godfather.”

Though Coppola wanted him, Pacino pointed out, “Nobody else did!”

He got the part, but studio execs pushed to fire him. We watched a scene that Pacino thought, even hoped, would be his last on the film – Michael’s escape from Louis’ Restaurant after fatally shooting Sollozzo and Captain McCluskey. Running outside, he jumps onto the getaway car but misses and falls.

Pacino believed he’d busted his ankle. His thought? “Thank you, God. I’m gonna get out of this film!”

That’s right: Al Pacino was relieved. He thought he was so badly injured, he could get out of “The Godfather.” Thankfully, his ankle healed, and the kid stayed in the picture.

A string of hits followed, including “Serpico” and “Dog Day Afternoon,” where an ad lib became a classic cinematic moment:

“This great AD, assistant director, comes running up to me as I’m about to go out and says, ‘Say Attica.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Say Attica. Say Attica.’ And the crowd just went into spasm and they all – they knew it. They were right in it.”

All the attention, all the success didn’t sit well with Pacino. He coped by drinking. “Alcohol is a depressant – like, literally it brings you down,” he said.

Mankiewicz asked, “And how’d your life change when you stopped?”

“Well, it got a little worse for a while,” Pacino laughed. “It really was terrible. But then, eventually, thank God, it got there.”

In his memoir, he’s candid about his struggles with alcoholism. He also reveals that he nearly died from COVID. “Out of this world,” he said. “I mean, I was here and then I wasn’t. The nurse said my pulse stopped. Now, I don’t think my pulse stopped.”

“But it doesn’t really matter whether technically you were close to death or not. You felt it,” said Mankiewicz.

“I did. I really did,” Pacino said. “It was so real. And I didn’t see any light. I didn’t see anything at all. There’s a speech in ‘Hamlet’ where he says, ‘To be or not to be.’ You know? And then when he talks about leaving the Earth when you die, and he says, ‘No more. No more.’ How about that?”

These days, there’s plenty more for Al Pacino. He’s as busy as ever. “I like sitting on the couch. But I keep working,” he said. “I’ve got six films. Smaller roles, of course. And they haven’t come out yet.”

And, despite that advice from his therapist, he’s living in L.A. But he is not, he assures us, an “L.A. guy.”

“No. I don’t think so,” he laughed. “I still speak English. In L.A., they speak Hollywood!”

Truth is, this is where they make movies. A fitting place for a guy who remains what he’s always been: an actor, still experiencing the same buzz he felt 60 years ago on an Off-Broadway stage in New York, which he described as a recognition that “I’m never gonna do anything else but this. I have found it. I don’t care what happens to me, whether I succeed, not succeed, didn’t matter. I had this.”

Mankiewicz said, “You write that, like, ‘Maybe I’ll be able to eat or I won’t eat. Maybe I’ll have money or I won’t have money. Maybe I’ll become famous. Maybe I won’t. Doesn’t matter.'”

“Didn’t matter,” said Pacino. “That’s the freedom. This was where I belonged.”

WEB EXTRA: Watch an extended interview with Al Pacino

For more info:

Story produced by Gabriel Falcon. Editor: Steven Tyler.

See also:

Source : Cbs News