Starved of social interaction by lockdown restrictions in the spring of 2020, tens of millions of people turned to Houseparty. The app let people dive into group video chats at will, provided they were friends with at least one other participant. The idea was to mimic the organic way in which people might be introduced to one another in the real world. The viral popularity of Houseparty proved to be short-lived; but the app had a certain je ne sais quoi that made it feel—if only for a little while—like something new.

The cocreator of Houseparty, Ben Rubin, who sold the app to Epic Games in 2019 for a reported $35 million, says he is still searching for answers to the question he was probing back then: How can the digital world be turned into a stage for interactions that wouldn’t otherwise be possible?

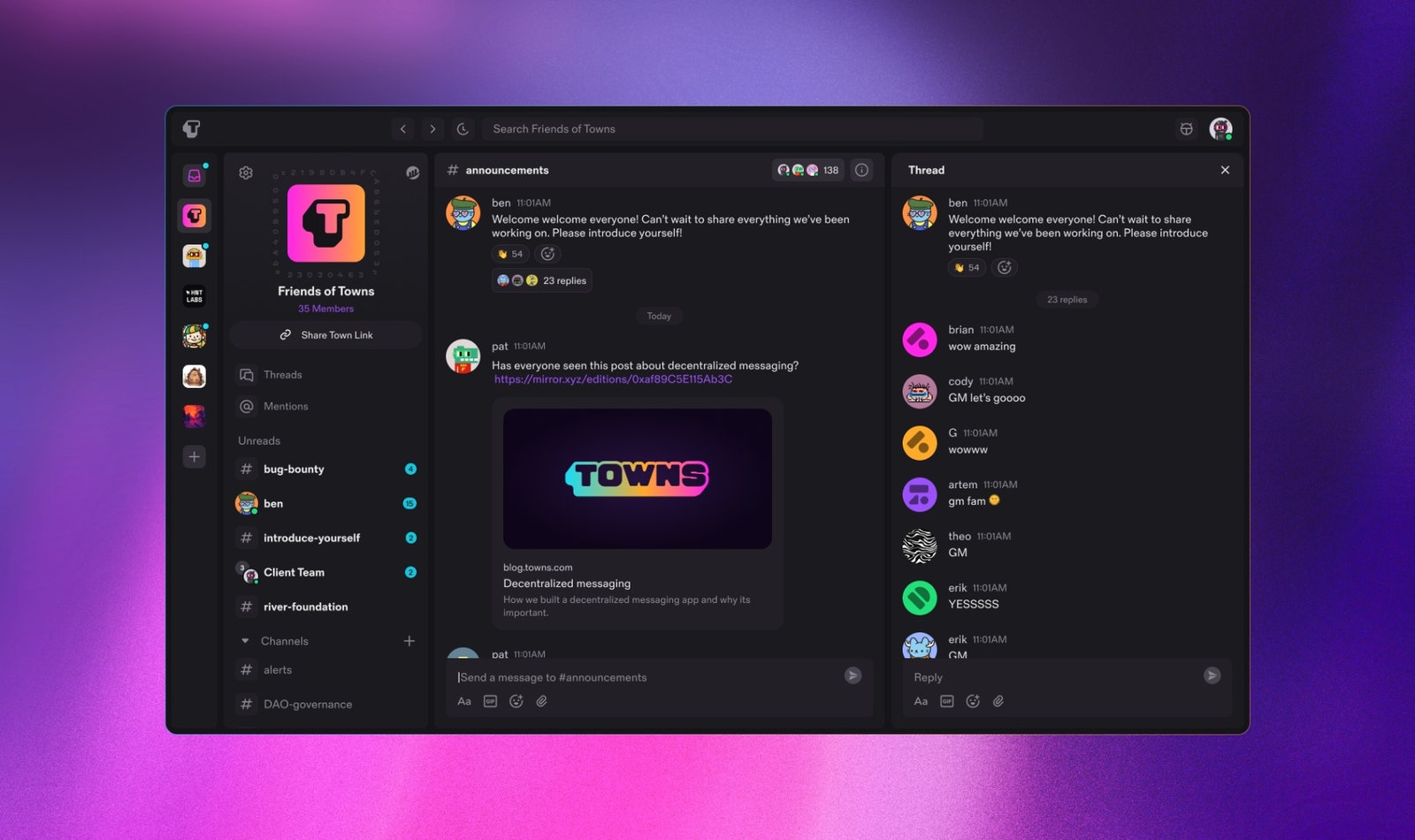

Rubin is currently the CEO at Here Not There Labs (HNT), which he cofounded in 2020 with Brian Meek, a former Skype engineer. In 2023, the company pitched its vision to investors, raising $25 million in a Series A round led by VC firm a16z. On October 15, HNT launched its first offering: a new group messaging platform called Towns. It may feel a lot like Discord or WhatsApp—a quick way to send messages and media amongst members of a group—but Rubin wants Towns to organize people in a different way.

Group chats on Towns can be configured in such a way that only people who fulfill certain criteria—who have specific expertise, say—are allowed to post messages, while everyone else watches from the sidelines. In this scenario, Rubin hopes, large group conversations will no longer be polluted with ill-informed takes and scam posts. He believes the ability for someone to prove that they are a real person using blockchain-based credentials, meanwhile, could help to minimize the opportunity for malicious actors to manipulate public discourse with bots.

The whole endeavor is a gamble that people will want their data—not only identifying information, but details about their activities, spending habits, etc.—etched onto a blockchain in the years ahead. If they’re willing, Rubin theorizes, that data could be used to group people together based on shared experiences and attributes. Towns could have a group for people who attended the latest Taylor Swift tour, or those who hold a qualification in cybersecurity, or anyone who frequently eats out in New York.

Rubin spoke to WIRED about his plan for putting that vision into practice and navigating the thorny problems—around moderation, policing misuse, and echo chamber effects—that have dogged the incumbents he now hopes Towns can overthrow.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Joel Khalili: Can you start by explaining how you came to the idea for Towns?

Ben Rubin: I started my career as an architect. Having studied the architecture of real buildings, one of the things that is still a guiding force in everything I do is how you bring people together in very unique ways. I still look at myself as an architect today. It’s just that the medium that I work in is digital.

So it wasn’t just about building a Houseparty follow-up or taking on Discord and WhatsApp.

As we become more and more connected, there is an opportunity to create spaces for people that actually affect how conversations are happening, what intimacy looks like, and so on. There are some things that you cannot do with bricks that you can do with the digital world, and obviously vice versa.

Of course.

One of the interesting things about Houseparty is that it was a double opt-in graph—like the Facebook graph—where I ask you for friendship, then you need to accept it. It’s not just that I follow you, as with Instagram. But the moment that happens, every time you are now in a conversation with your friends—just like at a houseparty where you might be talking to somebody I don’t know—I can go and say, “Hey.”

[With Towns], we are continuing this mission of showing people different ways to come together. I want to explore whether there are more people like me that are excited about the idea of making the internet intimate, without making it smaller.

How can you do that?

One of the things emerging is this new type of graph where, using blockchain, we can for the first time put people together based on shared experiences. That’s a new type of experience that cannot happen anywhere else except on Towns.

What is the closest point of comparison to Towns in terms of user experience?

As a builder of products, I believe that you can either innovate on how you’re bringing people together—meaning the graph—or what they are doing when you bring them together. You can’t do both.

For example, with WhatsApp, the group chat was a whole new medium at the time, but it used the address book, a known graph. Whereas Houseparty used a familiar medium—the video chat—but a new way to come together.

Right.

I don’t want too much new, and I believe that a lot of people are like that. We want to be inspired, but we don’t want to enter an alien world. This is a long way of saying that [Towns] looks like WhatsApp or Discord. It’s familiar.

How would you explain the value of this model to someone who doesn’t think deeply or regularly about the technical structure or demographic makeup of the messaging platforms they use?

That’s something I ask myself every day. Here’s where I’m at so far: We are going to focus on a use case that people are doing somewhere else, but not being satisfied.

Have you ever been in a trading group chat on WhatsApp or Telegram? The moment it grows past 50 people, [participants] don’t know what people are trying to sell them under the hood. But what if there were a group chat where only people who have created more than $1 million in trading profit over the last 30 days are able to speak?

You would never find me in a New York foodie group. But there could be a Town where the only people that can post are people checking into new restaurants every day—and everyone else can only reply to them or react. I want to do that.

The bet here is that there is enough of a mass of on-chain footprint that we can start the beginnings of self-organized conversation around proven experiences. That’s something we don’t have.

Have you thought about how such a model might contribute to problems caused by echo chambers—by the information presented to people becoming homogenous by way of the circles in which they move?

One of the biggest problems with echo chambers is that we haven’t had portability of reputation. My bet would be that the dynamic of echo chambers would be meaningfully different if you were able to prove to other groups that you are highly ranked [in terms of credibility, as scored by other members of the same community].

When highly ranked users from a very liberal group and a very conservative group meet, if they know provably that this is a highly-ranked person of the opposing opinion, all of a sudden it’s a debate. All of a sudden, there is a duty to engage.

I think it’s really exciting to say we took the six most prominent community members of these echo chambers, who are having really fierce conversations, but they all have respect for one another.

I think it introduces a wild card that I really want to see unfold.

How do you plan to deal with questions around moderation that major social media and messaging platforms have encountered? Take the recent situation with the Telegram founder, or the ever-lasting debate over political partisanship.

It is absolutely the wrong idea to apply censorship on the protocol level, whether it is the worldwide web, email, or the River Protocol [a system for sending end-to-end encrypted messages over blockchain developed by the HNT team]. We do not want to exist in a place where fundamental utilities can be remotely taken back.

HNT 100 percent intends to comply with regulations around CSAM and IP infringement when it comes to moderation on the client level [i.e., in the Towns app]. That’s what we’ll do.

What does that look like in practice?

It means that we host the report and review. We allow users to snitch to us—to tell us they are seeing something wrong. We are paying a third-party firm to review and make an adjudication. If a message should be censored according to local laws, we will not show it on Towns.

It really depends where the information is being rendered to the end user. That’s where it should be regulated.

What does the business model look like? Where will you take your cut?

The idea is essentially, as long as we can afford it, to create numerous clients [consumer-facing apps like Towns] that are bespoke to different use cases of what you can do with the River Protocol—with Towns being the first one. We have ideas around dating; we have ideas around music.

The idea with Towns is to bring it to a point where it’s owned and operated by the community. At some point soon, we are going to make it completely open source. And the idea for HNT, after Towns, assuming there is enough of a success that warrants our existence, is to start to create exemplary use cases of what you can do with the River Protocol and utilize the referral fee that anyone can utilize [to generate revenue].

Was that a tough sell to investors? It seems like revenue generation is a long way down the line and the path is not all that certain.

I’m very lucky that I get to pitch these crazy ideas. We’ve got world-class people working in the team. We’ve got world-class people backing the team. They all agreed to a script that is high risk, high reward.

Unlike in the beginning of my career building digital spaces, I’ve completely let go of the idea that something must succeed. Everyday I just think about what will make today successful.

Maybe that’s even more scary to hear me say if you’re an investor.

Source : Wired