Nearly everywhere on earth, when you’re stuck in traffic, you’re still surrounded by the usual sea of heads attached to shoulders attached to arms attached to steering wheels. But in a tiny handful of places—in Los Angeles, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Wuhan, China—you can find yourself flanked by taxis with no one in the drivers’ seats, picking up passengers, unsupervised by any human. And if you live in one of those cities, the sight probably doesn’t even prompt a double-take anymore. It’s like the future is suspended between those who’ve never encountered it—and those who are already a little blind to it.

Granted, practically everyone has been numbed by the hype cycle. Autonomous cars—one of the canonical sci-fi conveniences—were the hottest thing in tech for a few years around 2018. Then a self-driving Uber being tested in Arizona killed a jaywalking pedestrian, regulatory scrutiny intensified, and a bunch of self-driving projects shut down amid a general period of disenchantment with tech. The whole autonomous driving industry started to seem less worthy of being taken seriously, if not completely on the ropes.

In reality it was a case of rope-a-dope. Investment capital kept pouring in. Since 2020, more than $11 billion has been committed to Alphabet subsidiary Waymo alone. And in the past few years, hundreds of empty electric Jaguar SUVs began cruising the streets in Waymo’s three US markets, eventually picking up passengers and charging them for rides. A similar fleet of white-SUV robotaxis fanned out across Wuhan around the same time, operated by the Baidu subsidiary Apollo Go. The long-imagined future is finally, quietly, here, and all signs point to it taking over fast. Waymo is about to start operating in two new US cities—Austin, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia—in early 2025. And autonomous rideshare cars are in various earlier stages of testing in Las Vegas, Houston, Detroit, Seattle, and at least seven other cities in China; also in Japan, the United Arab Emirates, Germany, South Korea, the UK, Sweden, and Singapore.

WIRED happens to have a bureau in one of Waymo’s first markets, which is both an asset and a challenge: The novelty of being on the road with a bunch of robots has largely worn off for us in San Francisco, too. Even our 90-year old mother, when she took her first Waymo ride, felt instantly comfortable with her new sci-fi chauffeur. “There was no ‘getting used to it,’” she said. (WIRED does not have a singular mother, of course, but this story has many authors. So we’ve decided to write in a collective voice—much as Alphabet likes to say it’s developing not a fleet of autonomous taxis but a single “Waymo driver.”)

To provide the most useful dispatch from the future, then, we realized we needed a way to make self-driving cars feel strange again. A way to scare up the less superficial lessons of our city’s years with Waymo. We got to thinking.

San Francisco has provided a backdrop for: (A) the dawn of the ubiquitous self-driving taxi; and (B) at least one of the most iconic car chase scenes in movie history. So WIRED decided that the best way to juice some meaning and adrenaline out of the self-driving future would be to tail it in hot pursuit.

Our idea: We’ll pile a few of us into an old-fashioned, human-piloted hired car, then follow a single Waymo robotaxi wherever it goes for a whole workday. We’ll study its movements, its relationship to life on the streets, its whole self-driving gestalt. We’ll interview as many of its passengers as will speak to us, and observe it through the eyes of the kind of human driver it’s designed to replace. We’ll chase it for no fewer than six hours, or until we get into a fiery crash. Whichever comes first.

On the appointed morning, we assemble in a parking lot outside the WIRED offices to meet the driver of our chase car. If you’re blinded by the glare as he approaches, then let us tell you: He looks exactly like Steve McQueen, the race-car-driving star of Bullitt.

OK, fine, he looks nothing like Steve McQueen. If anything he vaguely resembles Jean Reno, the five-o’clock-shadowed French-Moroccan action hero from another movie with a classic car chase, Ronin. Only our guy is friendlier, gabbier, more fond of dad jokes, less ex-military-assassin-ish. His name is Gabe Ets-Hokin.

A third-generation San Franciscan, Gabe says he grew up playing with Nancy Pelosi’s kids and went to high school with Gavin Newsom, and now he’s a driver the way they’re politicians—it’s in his blood. He’s been operating taxicabs, Ubers, or Lyfts since 1995, and even helped organize a taxi workers’ strike in the late ’90s. He has also written about driving, ride-hailing, or motorcycling for the past two decades. And if you think we’re being silly about car-chase movie tropes, Gabe was a machine-gunner for the US Marines during the first Gulf War—so he is at least ex-military. He’s driving a gray Hyundai Ioniq 5 EV (9/10, WIRED recommends) and keeps his military service ribbons affixed to the dashboard. There’s also a 100-year-old ukulele poking out of the center console.

The chase begins as planned: One of us hails a Waymo a few blocks away, rides it to the edge of the parking lot, then bolts to join the others in our pursuit vehicle. “You know what you have to say, right?” Gabe says from the driver’s seat as we scramble to buckle up. WIRED blinks.

“Come on!” Gabe says. “Haven’t you ever seen old movies? You jump in the cab and you say, “Follow that car!”

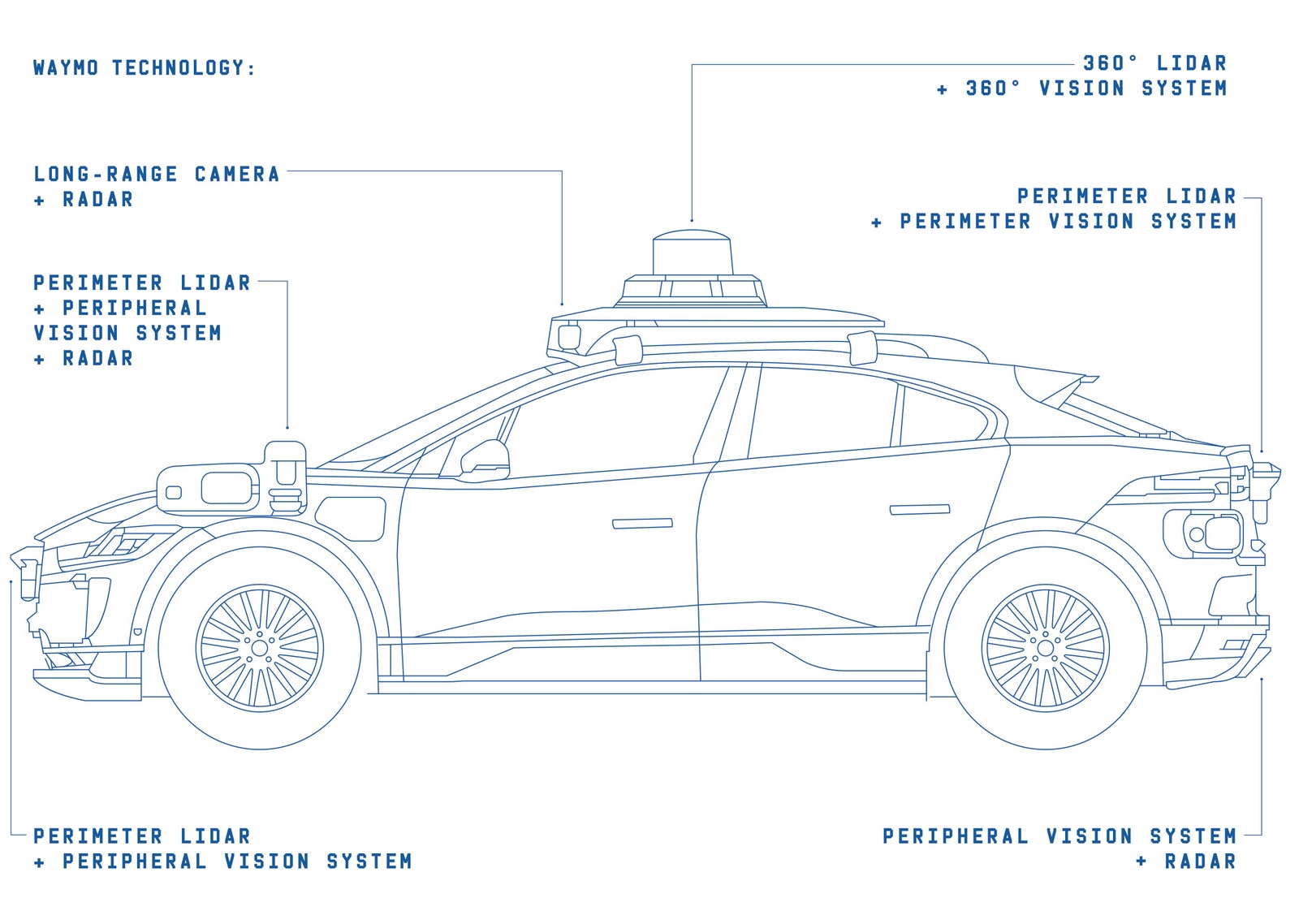

But the Waymo just sits there. For two agonizing minutes. Plenty of time for us to stare awkwardly at our quarry—a vehicle whose shape recalls a cartoon shark with a bunch of spinning doodads implanted in its skin—as it stares back at us through its 29 cameras and five lidars, mapping our contours.

“It looks shy,” says Gabe.

“It’s ashamed. It’s so ashamed,” WIRED says. “It knows it’s being tricked.”

Then, at 10:42 am, the Waymo starts to move. WIRED shouts, “Follow that car!”

Less than a minute later, Gabe sighs. “I’m not used to driving this slow.”

Before we go any further, let’s get something out of the way: Riding around inside a self-driving vehicle, especially for the first time, is an immediately cool experience. It starts out like an amusement park ride—the empty gondola sidles up, you step in, you shut the door. Then it becomes the opposite of an amusement park ride. No thrills. No lurches. No clatter. Just you, some soft black leather, a default computer voice, and—for now—a steering wheel, ghostly turning this way and that.

Reddit and Substack and X are full of paeans to Waymo first rides, many comparing them favorably against the “nasty” experience of Uber and Lyft. (Social media also has its share of clips showing confused and stuck Waymos and scenes of violence against autonomous SUVs.) The paeans all tend to sound a couple of major themes. WIRED’s mother—who is, again, 90 years old—echoed both of them after her first Waymo ride with us. “I felt secure that there was a really responsible driver in charge, who knew all the rules and would follow them,” she said. “You aren’t taking a chance like with a human being.” And even though she knew she was surrounded by sensors and microphones and computers, she didn’t feel overheard or interrupted. “Our conversation in the car felt more private,” she said. “There wasn’t another person taking part.”

Here in the chase car, Gabe is very much taking part. Which is good, because he’s easily the most interesting person on board. He seems able to reel off stories about practically every block of San Francisco (Those are the projects where O.J. Simpson grew up. That’s the public library where the creator of the Silk Road dark market was busted. There’s the Safeway where mayor Ed Lee collapsed from a fatal heart attack).

So far Gabe seems to be feeling pretty cocky about squaring up against his machine replacement. From his sporadic prior experience sharing the road with Waymos, Gabe’s impression is that they’re pokey and plodding, rule-followers to a fault. So far our Waymo—license plate 53516F3—isn’t doing anything to break that stereotype. “It drives better than my mom, but she’s 85,” Gabe says. He gestures at the speedometer. “Look at it. Exactly the speed limit.”

“Would you rather that there were more of these on the road than humans, just in terms of the driving style?” WIRED asks as our Waymo accelerates from a stop with the serenity of someone doing their morning tai chi. Gabe literally shudders. “I think that would slow down traffic tremendously.”

“But then there would be fewer lives lost,” WIRED says. “That’s the whole point.”

“I don’t know, would there really be that many fewer lives lost?” Gabe says. “People die in surface-street collisions very infrequently.” Then he ups the utopian ante: “I mean, we could do things to totally eliminate traffic deaths. What’s going to eliminate traffic and pedestrian deaths is moving cities away from being dependent on cars—and autonomous vehicles do exactly the opposite, by definition.”

“If this is the future of urban transportation,” he says, motioning up at 53516F3’s lidar-whirling rear end, “then we have to keep designing cities with giant streets and giant parking lots and traffic lights and traffic lanes and all this infrastructure that takes up so much space and benefits so few people proportionally.”

We are momentarily confused. “Moving away from cars would be something you’re in favor of?” WIRED asks.

“Yeah!” Gabe says as we keep rolling south. (Turns out Gabe is something even more enigmatic than an ex-military assassin: an ex-military urban-planning nerd.) Cities built for many fewer private cars would just be good for the world, he says. And around the edges, they’d be good for ride-hailing too: “If you don’t own a car, you’re more likely to use Uber or Lyft.”

Or hail a Waymo, we might counter. But we’re preoccupied thinking about the day ahead. We start to wonder: When our Waymo picks up its first fare, will the passengers notice they’re being tailed by a car full of people scribbling notes and holding up video cameras? When we hop out to interview them at their destination, will they accuse us of stalking? Will we trip some algorithmic alarm that alerts Waymo we’re tailing its driver?

The more we watch the streets, the more we realize our worries are moot. There are enough tourists in San Francisco that our Waymo attracts gawkers like a parade float.

They’re also moot because 53516F3 doesn’t pick up any passengers: After less than 30 minutes on the road, it turns left into a fenced-in lot across from a budget grocery store. There are no electric-car chargers to be seen, but the lot is teeming with empty Waymos, either parked or pulling in and out, each one with all its lidars still spinning. The overall visual effect is of a writhing hive. (Stretched out across a neighboring rooftop is a 40-foot-long wire sculpture of a reclining naked woman, a remnant of Burning Man; it’s like she’s a nudist at a picnic invaded by robot ants.)

We settle in to wait for 53516F3 to reemerge. Gabe takes out his ukulele. After about 10 minutes, we decide to abandon our plan to tail a single vehicle. So we pick a random new robotaxi drone on its way out of the hive: 40757F3. Off we go, running a perfect 25 mph down Bryant Street, passing so close to our office that a coworker who’s tracking our location snaps a picture of us from the window. And after 20 minutes, 40757F3 leads us … straight to another Waymo lot a few blocks from WIRED.

This time we pick up the trail of the first robotaxi to exit: plate 78889X3.

We have high hopes for this one at first, but then we notice it has a yellow “low battery” indicator on its dome. “If it’s going to a lot, I’m going to scream,” WIRED says. Sure enough, 78889X3 takes us 3 miles south to a charging and maintenance lot deep in an industrial zone under an elevated freeway. As we wait outside the fence for our next mark, a man offers us a swig from his vodka bottle. We decline. So does our mood. When we see a new Waymo coming out, 53499F3, WIRED monotones: “Follow that car.”

It’s about 11:30 am. Late morning can be the quietest part of the day, Gabe says; according to his Uber and Lyft apps, demand for rides has been pretty much comatose since we started. But all this deadheading between parking lots makes us think more about Gabe’s prediction of the urban future. People lament that most cars on the road today are 4,000-pound contraptions with just one person in them. Is Waymo going to make congestion worse by filling the streets with 5,000-pound contraptions that are completely empty?

When we ask Waymo’s chief product officer, Saswat Panigrahi, about all the empty robot-shuffling, he calls it “rebalancing the fleet.” During slow periods, he says, cars will automatically distribute themselves into an ideal position to meet an expected peak demand later on; they’ll also pick the optimal time to go recharge. As ridership increases later in the day, we’ll see fewer empty Waymos about town.

On the larger question of how Waymo will reshape the future of cities, Panigrahi is excited to talk. At times he sounds like a throwback evangelist for the rideshare revolution from the mid-2010s.

Back then, Uber’s brash CEO, Travis Kalanick, loved to inveigh against the evils and inefficiencies of car culture. “Around 20 percent to 30 percent of our land is taken up just storing these hunks of metal that we drive around in for 4 percent of the day,” he said in 2016. Here in 2024, Panigrahi laments how “in cities, there’s more space reserved for cars than for humans.”

Kalanick’s big promise was that Uber would bring about the extinction of private car ownership and an end to urban congestion. Panigrahi isn’t quite so hyperbolic, but he does suggest that Waymo will bring about a world with “fewer metal things consuming vital real estate” in cities. Gabe, of course, assumes the opposite: that autonomous vehicles will result in more congestion. So who’s right?

According to Adam Millard-Ball, an urban planning professor who studies autonomous cars, the past 15 years of Uber and Lyft should offer a decent preview of how robotaxis will affect traffic. (Because with or without a driver, both are private taxi services with a layer of algorithmic efficiency baked in.) And research suggests that in fact Uber and Lyft brought more private cars onto city streets, partly because drivers acquired new ones to gig for the platforms. All that led to—you guessed it—more congestion.

No one will be buying a new car to gig for Waymo, of course. But driverless vehicles could conceivably bring even more gridlock, Millard-Ball posits, mainly because of the way cities fail to price roads. In busy downtowns, driving is free. It’s the price of parking that typically pressures car owners to take some other mode of transit. Witness, for example, the $1,000 parking spots that have followed Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, and the corresponding spike in public transit usage trailing the singer around the world. Trouble is, robots don’t need to park downtown. And it’s possible they could make ride-hailing itself more affordable (we’ll come back to the economics of Waymo later), since there are no Gabes to pay. So: cheap, easy-to-use, widely available private cars on the roads. It’s a recipe for endless traffic.

What about self-driving buses? Waymo says that its “driver” could ultimately be made to pilot trucks, delivery vehicles, large people movers, you name it. The trouble is that it’s hard to save money on labor with self-driving buses; when dozens of lives are at stake in a single vehicle, cities will probably need to keep paying a human minder to supervise robot and passengers alike.

In other words, tech alone probably won’t make cities magically work better, says Millard-Ball; that takes policy too. If cities started charging people to drive on downtown streets, for instance, not just to park on them, that could further disincentivize car rides—nudging more people onto climate-friendlier buses, trains, bikes, and the occasional ride-hail around the edges. Uber and Lyft are actually really into this idea. In New York City, the companies joined urbanists in lobbying for a “congestion charge” that would have forced drivers to pay to access the streets of Manhattan. After some political wrangling and delays, the revolutionary congestion program will finally kick in—charging most drivers $9 to enter the lower half of Manhattan, and raising an estimated $500 million a year for transit—this coming January.

The thing about the arrival of a big new technology—particularly when it needs approval to gain access to each new jurisdiction—is that it provides a natural opportunity for big policy discussions, says Millard-Ball. Cities could demand, for instance, that Waymo fork over the kind of data that Uber and Lyft have sometimes been stingy with—data that might help cities measure congestion and accurately charge drivers for using city streets according to fluctuations in demand. Cities could also compel Waymo to play nice with mass transit, as it’s already doing for brownie points in San Francisco: In October, Waymo announced a new program that awards customers credits for future trips if they begin or end their rides near public transit stops. In other words, there is a world in which the story of self-driving taxis might be more fairy tale than nightmare. It’s just that cities have to bargain for it.

That’s way out in the future, though. Here in the present, we’re still a car full of journalists and a driver chasing an empty robot through a warehouse district, respectively fending off the need to pee and our own obsolescence.

“Remember Uber going on about the taxi mafia?” Gabe asks a few minutes after we leave the charging depot. “How Big Taxi wanted to crush Uber? How Uber was this poor little upstart company?” He gestures out the passenger window at what looks like a seedy impound lot with a brown portable building for an office, a bunch of grimy yellow Priuses scattered about. “So … this is where Yellow Cab had to move after bankruptcy. That’s Big Taxi.”

Perhaps it’s just his inner Big Bus tour guide, but Gabe somehow sounds more chipper than resentful. Surfing waves of creative destruction seems to have become second nature for him. Remember that taxi workers’ strike he helped organize in the late ’90s? Gabe was driving for Yellow Cab at the time. The strike was an attempt to keep the mayor from expanding San Francisco’s supply of taxi medallions to add 500 cabbies to the workforce. Gabe was worried it would cause wages to plummet.

Twelve years later Uber arrived, and San Francisco was the first beachhead for its mass invasion of thousands of new drivers. The internet was once full of paeans to riding in Ubers, too: how plentiful they were, how nice the cars could be, how convenient it was to push a button and watch your driver approach on a screen. Backed by venture cash and happy to operate at a loss, Uber priced rides fancifully low. Yellow Cab didn’t stand a chance. Now, with apparent equanimity and maybe even a sense of wonder, Gabe can rattle off how, in the mid-’90s, he used to earn $30 to take someone between Oakland and San Francisco—while just this morning, three decades later, the same ride earned him a measly 24 bucks. Is history just going to repeat itself now?

We are just over two hours into the chase, at 12:39 pm, when our fourth Waymo picks up our first fare of the day. It happens on a picturesque residential street in the foggy Sunset District, near Golden Gate Park. A young couple dressed all in black comes out of a house, both filming as they walk up to the Waymo, its rooftop display flashing their initials. “Look at them,” Gabe says from our safe distance down the street. “It’s like it’s Christmas. Look how happy they are.”

The robotaxi whisks the couple northeast, past the Victorian houses from the TV show Full House (“I used to see Bob Saget in comedy shows,” says Gabe), the old St. Mary’s Cathedral (“The bricks around the foundation were ballast from sailing ships”), and the spot where an empty Waymo was recently set upon by a mob and then allegedly lit on fire by a teenager. After 39 minutes, at 1:23 pm, we pull to a stop in North Beach, in front of City Lights booksellers, and two of us hop out to flag the couple down.

When WIRED lets on that it’s been following them, both passengers look like they’ve just swallowed a bug. But however flummoxed Andrew Dong is by us, he’s unequivocal about Waymo: “Probably the best rideshare experience I’ve ever had.” He loved—as everyone seems to—that there was no stranger in the car and how smooth the ride was. (This is another recurring theme in paeans to Waymo: The stops are less stoppy, the starts less starty.) Dong is a software engineer visiting from New York and says if he had the option, he’d never hail another Uber or Lyft again. “This is all I would take.”

What he means, really, is that he’d never hire another human driver again. Uber’s endgame has always been a fleet of self-driving cars. And though Uber and Lyft have both listed Waymo as a potential direct competitor, for now they’re more like frenemies with Alphabet’s self-driving division. Lyft offered robotaxi rides in Phoenix via Waymo for a brief period before the pandemic, and the two companies remain in open dialog; Uber started offering driverless Waymo rides there last year. And when Waymo expands into Atlanta and Austin, it will eventually do so exclusively through the Uber app. Taxis got rolled in the last wave of creative destruction. This time, it will just be humans.

The logical conclusion may be a world with barely any hired human drivers at all, but for now, high Waymo fares and a short supply of robotaxis are holding off that future. Waymo rides are, anecdotally, slightly more expensive than Lyft or Uber fares with human drivers. According to Panigrahi, this is partly a formula for keeping wait times down; if prices go too low, then too many people try to hail Waymos and end up waiting 25 minutes. “Even if we’ve tried very hard to keep excitement low, the demand far outstrips our gradual expansion,” Panigrahi says. But eventually, he says, the price will start to fall.

How far? Just as with Uber in the early days, it’s difficult to tell what the real underlying economics of Waymo are. It’s part of a historically rich corporation with some $93 billion in cash on hand. Plus it also has outside investors, including the private equity giant Silver Lake, the sovereign wealth fund of Abu Dhabi, the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz. With technology this expensive to develop—remember, it’s been about 15 years since Google first began developing autonomous driving—investors know they have to be patient.

Now that Waymo is earning revenue, assessing its business prospects is a matter of rough guesses. Waymo hasn’t publicly stated how long its cars last, what their maintenance costs are, or how long they idle during the day. But in August, some financial analysts at the bank Citizens JMP published a report that assumed a Waymo SUV lasts two years, costs about $70,000 a year in hardware, $41,000 a year to operate, and serves nearly 16 rides per day in San Francisco. Based on those figures, Waymo would generate $112,000 in annual revenue per car in San Francisco, compared to $111,000 in annual costs—barely squeezing out what analysts call a “unit profit.” When that report came out, Waymo was racking up 100,000 paid trips per week; by October, it was up to 150,000.

Panigrahi wouldn’t say much about specific growth plans, investment payoff horizons, or financial details, but he did say that Waymo has “a pretty robust revenue on a per-car unit basis, as well as on a market level.” And he’s confident about the direction ahead for society. “Cars will drive people,” he says. “People won’t need to drive cars.”

In an August podcast interview, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said that Uber riders in Phoenix chose a robot driver only about half the time when given the option, and they’re giving the robots lower ratings. But Khosrowshahi fully expects autonomous vehicles to eventually bring the cost of Uber rideshares down significantly for riders, and Uber is partnering with Waymo-like companies around the world. “Ten to 15 years from now, I think it’s going to be a real part of our business,” he said.

For some people, the prices don’t seem to matter much already. Andrew Boone, one of the analysts from JMP, says that in a survey of junior bankers in San Francisco, his team found a strong preference for the sleek, white, driverless Waymo Jaguars—despite what riders reported as higher prices, lengthier waits, and longer walks from drop-offs and to pickups. Even when it’s an inferior service, Boone says, “people really prefer not to have a driver in the car.”

Outside City Lights, Andrew Dong says one more thing about his Waymo ride that sticks out. “We thought it’d be slow and stupid,” he says. “But it wasn’t.” Over the course of the day, Gabe has been grudgingly coming to the same conclusion.

It started in the late morning, when he noticed our Waymos taking many of his favorite shortcuts. Now as traffic picks up into the afternoon, Gabe has more and more moments of respect for our robot prey. At one point our Waymo almost loses us by accelerating through a yellow light; Gabe floors it and barely gets in under the wire. “I’m surprised,” Gabe says. “It kind of ran the yellow, didn’t it?”

A few minutes later, the Waymo does lose us for a minute after turning left at a light we can’t catch. Gabe recovers by hanging an instant right and then doing a U-turn of questionable legality. His dignity is intact, but he’s a little stung.

Those are the Waymo driver’s frisky moments. At other times Gabe is impressed with its strategic caution. At one stoplight, he studies 53499F3 like it’s a horse at a starting gate. “Do you see how they program it to not charge out into the intersection as soon as the light turns green?” he says. “That’s how a cabbie would drive.”

When Gabe was a taxi driver, he says, there was a big banner at the cab yard with driving tips on it. One of them was “never be the first car into an intersection,” because you never know when someone’s going to run a red light. “Cabbies are all about knowing when to drive aggressively and when to drive carefully,” Gabe says. So, it seems, are robo-cabbies.

“They’re programming them right, I think,” he marvels. “If I didn’t know it was a robot, I would just assume it was a very careful commercial driver.” The chase has become eerie for Gabe. “There’s something weirdly dislocating about watching a robot do the same trips that I’ve done thousands of times.”

One reason the Waymo’s driving may seem livelier—making sudden U-turns and turning left across multiple lanes—is that the rides are picking up, one after another. Our next passengers, a couple that look to be in their early thirties, get in at 1:35 pm in front of the Fairmont Hotel (where, three months later, a robotaxi will get stuck in the path of Kamala Harris’ motorcade). They get dropped off at Coit Tower; tourists from Florida, they’d never even heard of Waymos until they started seeing them around town.

We head back down Telegraph Hill and at 1:47—after we catch some Mennonites with flip phones gawking at our Waymo—another rider gets in. He looks as if it’s his 20th time in a robotaxi. A youngish guy in Allbirds, he gets out in front of an office building at 2:04 but doesn’t want to talk to us. At 2:14, near the Salesforce Tower, another rider gets in: a local woman heading to a nail salon in the Haight District. She’s been using Waymo regularly for six months. She loves it, loves having the space to herself. But she did once have to call customer support, because her car got confused by some traffic cones.

Around hour four, we watch in amazement as a well-dressed pedestrian stands in the middle of a four-lane street to film our Waymo with his phone. “That man did not care about getting run over,” WIRED says.

“We have no natural predators,” says Gabe, as if this weren’t a non sequitur. “On one random day every year I think the city should release a tiger until it kills one person, then put the tiger back for another year,” he says. “That way they can put signs everywhere that say, ‘Wild animals. Danger. Be aware of your surroundings.’ That would save so many pedestrians’ lives.”

“Interesting,” WIRED says warily, politely. “So it’s a trolley-problem kind of thing.”

“But check it out,” Gabe says. “I think it is a very similar argument that the tech companies are making about autonomous vehicles. Because what they’re saying is, well, there might be a few deaths from very unusual situations—but overall the rate will decline. So I think my idea is perfect.”

“Plus,” he says, “think of the tourism opportunities.”

Gabe, at this point, is all the more soured on Waymo. He’s seen how well it can drive—how the steam drill is destined to beat John Henry—but he also feels more confirmed in his sense that, as Waymo gets cheaper, it’ll just encourage more single-vehicle transport. “It doesn’t change anything,” he says. “There’s no real change. All you’re doing is making labor cheaper.”

But Gabe keeps ignoring, or else mocking, the biggest change Waymo promises: that it will save lives. This is the one area where Panigrahi makes a truly hard sell. “If I told you there’s a driver that can reduce injuries by 72 percent, you should ask me, ‘Why not sooner? Why should we be OK with this many people dying on the road?’” Panigrahi points to the reams of data Waymo publishes on its accident rates relative to human drivers; the company is aggressively transparent on this front, disclosing even more data than regulators require. Safety is its dominant marketing pitch.

But it’s also inevitable that, at some point, the tiger is going to get loose and kill someone. The first time a human was killed by an autonomous vehicle, in Tempe, Arizona, it helped spell the end of Uber’s own self-driving initiatives. And when a vehicle operated by Waymo’s rival, Cruise, was involved in a serious crash in San Francisco last year, reportedly leaving a pedestrian hospitalized for months, the company lost its permit to operate in California and suspended operations nationwide. It didn’t help that the company failed to disclose vital details about the incident to regulators. The real test of whether the future will take hold this time may be in how Waymo handles its first fatality.

As we hit the five-hour mark, we start to worry we’ve been driving too long—for our sanity, if not safety. “Is there a nap time scheduled?” Gabe asks.

Our last fare of the day is a white-bearded man who gets picked up outside an apartment complex at 3:54 pm, then dropped off a short distance away, near a UPS store in the Financial District. His name is Sean O’Brien, and he’s a 75-year-old local. He’s been taking Waymos for the past couple of months, he says, and loves it. WIRED’s mother, who quit driving two years ago, lives outside the Waymo coverage area. But seeing O’Brien run errands in a robotaxi makes us wish she could do that too.

Like everyone else, O’Brien has the usual refrain when he gets out at the UPS store: “I got tired of Lyft, and the drivers, and the talking and everything.” By now, after six hours on the road, Gabe kind of agrees that he’s tired of it too. “I kinda wish I was a robot,” he says as a parting thought, “so my ass wouldn’t hurt so much.”

(Logistical support at WIRED’s home base by Tom Simonite.)

Source : Wired