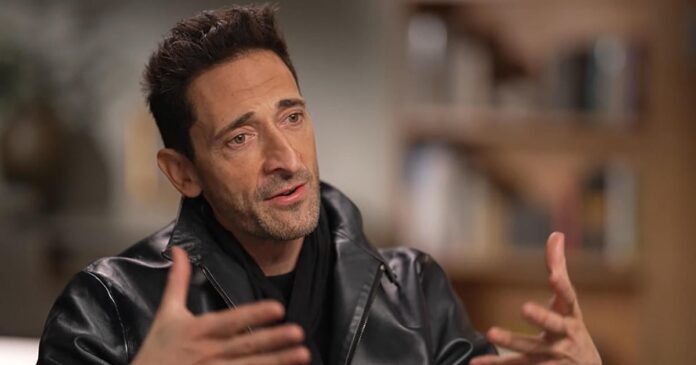

Last month, on a boat called the Manhattan, Adrien Brody and I sailed into New York Harbor. Destination: The Statue of Liberty. He’d been to the landmark before, spending time there with his mother, an immigrant who came to America in 1958.

“My mother and my grandparents fled Hungary during the revolution,” Brody said. “There was so much unknown, and a lot of loss. And all of those sacrifices have kind of laid the foundation for my own existence and what has been accessible to me.”

Brody’s immigrant roots make his latest film, “The Brutalist,” a deeply personal one. It’s a sweeping, decades-long tale of love, ambition, and a complicated American Dream, all centered around one man, László Toth. “He’s a Jewish Hungarian architect who survives the horrors of World War II, and is forced to toil through poverty and rebuild,” Brody said.

Toth is hired by a wealthy industrialist to build a massive community center in his “brutalist” style – a form of architecture that’s light on decoration and heavy on concrete.

To get Toth just right, Brody drew on his memories of his Hungarian grandfather. “I remember my grandfather’s accent was very, very heavy,” he said.

“So, do you hear your grandfather’s voice a little bit in this character of László?” I asked.

“Oh definitely, yeah, I conjure it up. I also knew every bad word in Hungarian as a kid. So, I infused some of that in it that’s not in the script!”

To watch a trailer for “The Brutalist” click on the video player below:

The film’s received seven Golden Globe nominations, and Oscar buzz is high. But at three-and-a-half hours, it requires a commitment.

Asked if he was worried about the film’s length, Broday replied, “This is an event. Generations before us, you could expect to see something like this in a theater. But that’s becoming much more rare today. I think we all need to be fed nourishing meals! And this is one of them.”

At 51, Brody’s portrayal of a man rebuilding his life after a war makes for a fascinating counterpoint to a role he played more than two decades ago: his Oscar-winning performance of a man enduring the horrors of war in Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist.”

To play Wladyslaw Szpilman, the real-life pianist who survived the Nazi occupation of Poland, Brody virtually starved himself, losing 30 pounds, all while learning to play the piano.

Learning to play Chopin, he said, quelled his pangs of hunger. “‘Cause it was a kind of meditative, intensely-focused activity where I was memorizing. And I became quite proficient at playing minutes of Chopin’s Nocturne and a ballade. And I don’t even read music.”

At 29, he was the youngest man to ever win the Oscar for best actor. The child of an immigrant was living his own American dream.

Adrien Brody was raised in Queens, N.Y. His father, Elliot, is a retired teacher. His mother, Sylvia Plachy, is a photographer. “As an only child and the son of a photographer, I was her favorite subject,” he said. “And so, I had a lens from a very nurturing and ever-present perspective on me. And I think that also helped as a film actor.”

“You were comfortable in front of a camera thanks to Mom?” I asked.

“Yes. Thanks to Mom.”

He dabbled in magic, calling himself “The Amazing Adrien,” but settled on acting by middle school. At 13, he landed a leading role as a rebellious orphan in a made-for-TV movie, “Home at Last.” “I remember thinking how I never wanted it to end,” he said. “And that sense of joy that I get from it in that immersion, it’s never gone away.”

Brody aged into a mohawked punk rocker in Spike Lee’s “Summer of Sam.” He’s carried a blockbuster like “King Kong,” and shown some whimsy in his five films with director Wes Anderson, including “The Darjeeling Limited” and “The French Dispatch.”

Anderson, said Brody, “has given me a lot of opportunity to do comedic work, more overtly comedic stuff, which at the time when we started working together, I think people just thought I was a serious actor.”

“The Brutalist” is a return to his serious side, and maybe a reminder that, as an artist, Adrien Brody is up for anything. “It’s a nice moment right now,” he said.

I asked, “When you’re not working, what makes you happy?”

“Lots of things. I need to be creatively immersed. So, that may be fulfilled through cooking, through painting, through making music. I’m a pretty good cook.”

“What do you make?”

“I mean, hot dogs,” he laughed. “What do you like? You tell me what would you like? I can whip something up. You can come over one day, come see the artwork. I’ll whip up something to eat. I can make some good cocktails.”

“You’re a mixologist as well?”

“Oh, I can hook it up.”

“Okay. What can you not do?”

“Keep my mouth shut!” he laughed. “I need to learn that one!”

For more info:

Story produced by Reid Orvedahl. Editor: George Pozderec.

Source : Cbs News