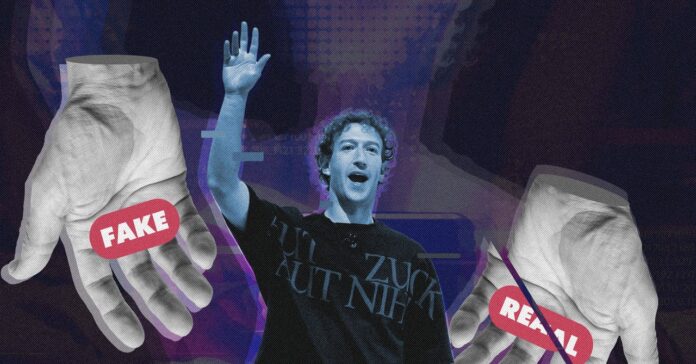

It was 2016, and the problem of fake news kept Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta (then called Facebook), up at night. The young entrepreneur was under pressure from the media and was also constantly questioned by the US legal system. The Cambridge Analytica case, accusations of Russian interference in the elections, and Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential race raised serious concerns. For the first time, the question of the platform’s influence on the political landscape was being addressed—US lawmakers demanded that the company “protect democracy.” Eventually, Zuckerberg would appear before the Senate in 2018.

As part of his counteroffensive, the company created the Third Party Fact-Checkers, or Independent Fact-checkers, program to address misinformation on its platforms.

The History of Independent Fact-Checkers at Facebook

First implemented in the United States and then in the rest of the world, the project seemed to be working. So far, according to its own data, there were more than 100 international organizations actively participating in it. Indeed, last year, in the context of the European Union parliamentary elections, Meta announced the effectiveness of its labeling system: “Between July and December 2023, for example, nearly 68 million posts on Facebook and Instagram had fact-checking labels. When something was labeled as false or misleading, 95 percent of people did not click on the content.”

But everything changed on January 7, when Mark Zuckerberg announced the end of the program in the United States. It seems only a matter of time before the initiative disappears in Latin America and the rest of the world, undermining independent news organizations that depend, to a greater or lesser extent, on that funding. Among those who would be affected will be Animal Político in Mexico; Chequeado in Argentina; Agencia Lupa or Aos Fatos in Brazil; and Maldita.es in Spain. Why get rid of something that was working, according to the company itself?

How Does Meta’s Third-Party Fact-Checker Program Work?

I was an editorial supervisor at Animal Político’s El Sabueso when Meta approached us to start the project. To be part of it, you had to join the Poynter Institute certification, an international organization funded by the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), which set the editorial rules for verifying information with a highly rigorous and transparent code of principles. Meta trusted this network for the project, and also had its own requirements. Among them: Political discourse or any type of content that was classified as an opinion could not be refuted. Statements by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) could not be questioned, for example, but misinformation about the first migrant caravan, which crossed Mexico in the first year of AMLO’s six-year term (2018) and which strengthened a racist anti-immigrant discourse, could be.

The “news” that was being debunked was photos or videos taken out of context, such as one that falsely claimed that a group of migrants had hijacked a truck in Chiapas. There were also lies about alleged kidnappings of children in Mexico and other Latin American countries. Then came the Covid-19 pandemic. Independent fact-checkers took on a leading role in debunking, with the available data, ideas such as “drinking bleach eliminates the virus” or “5G networks caused the pandemic.”

This 180-degree change is a response to Donald Trump’s imminent second presidential term and to the methods of the competition, such as X’s Community Notes. Meta decided not to invest any more money in its program. Now, it hopes that Facebook and Instagram users themselves will be the ones to decide what content is disinformation or not.

Source : Wired