From time to time, you might notice a shot of a clock in a movie. In a film like “Back to the Future,” they’re key to the plot; lightning strikes the clock tower at exactly 10:04 p.m. But often, clocks are just ticking away in the background, or not ticking at all, like the watch from “Pulp Fiction,” stopped at 11:46.

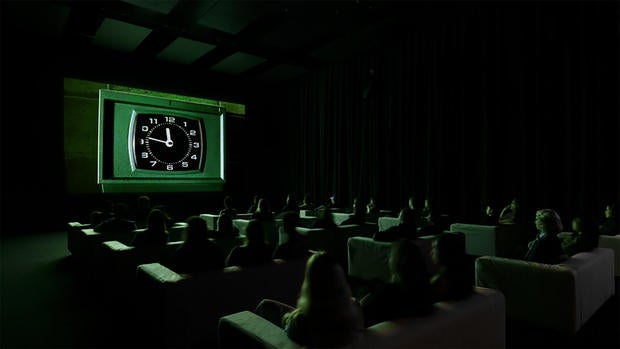

Compile enough of these seemingly minute details, and minutes can turn into hours, spanning decades of moving-image history. That is the case with artist Christian Marclay’s “The Clock,” a 24-hour film comprised entirely of clips from movies and television.

“It’s not to create a trick or to make you forget about time,” Marclay said. “I want you to be totally conscious about it throughout.”

Currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, “The Clock” runs on a continuous loop, synced to the precise time of day. When the kids in “The Breakfast Club” are whistling at 11:31 a.m., it’s 11:31 in real life. An hour later, “Rain Man” announces “Oh, it’s 12:31.” Minute by minute, the footage functions as an actual clock.

Stuart Comer, the chief curator of media and performance at MoMA, calls watching Maclay’s mash-up an uncanny experience. “[You’re] watching some of your favorite movies and realizing that it’s telling the time that you’re living in right now,” Comer said. “It’s eliminating that barrier between you and the world on-screen.

“The effort that it took with Christian and the team of researchers locating ‘The Clock’ footage and all of these different clips is somewhat superhuman,” he said.

When Marclay won best artist for “The Clock” at the 2011 Venice Biennale, it turned him into a contemporary art superstar. But the 70-year-old first made a name for himself decades earlier as part of New York’s underground DJ scene. “In those days, you would find records … people would put them in their trash,” he said.

Born to an American mother and Swiss father, Marclay was raised in Switzerland and moved to the U.S. to attend art school in the late 1970s. “I kept putting aside my work as a visual artist, ‘cause I lived in a tiny East Village apartment, and I didn’t have a studio,” he said. “So, music at that time was convenient.”

It was, he admitted, easier to store records than canvases. “But you need tolerant neighbors!” he laughed.

Marclay’s music was experimental. He was an early pioneer of “turntablism,” invited to spin on the short-lived show “Night Music.” “I would destroy the records in performance, but then I had all these incredible covers, such an interesting history of graphic design. And I started collaging with them.”

One of Marclay’s early successes in the visual art world arrived via his Body Mix series, in which he physically stitched together album covers to create new forms.

He’s unspooled cassette tapes to make prints and pillows. He’s cut up everything from Japanese manga to movie subtitles, stacking cinematic fragments nearly 20 feet tall. He said he felt more comfortable as a collagist: “I’m more interested in working with what exists rather than [to], you know, invent or draw something,” he said.

In 1995, Marclay created “Telephones,” a masterful mashup of film phone conversations.

It’s been more than a decade since “The Clock” was last in New York. Marclay is extremely precise about where and how it can be screened, insisting that any museum showing the work stay open at least once for 24 hours so audiences can see the nighttime section.

Are there “Clock” completists? “Oh, there are definitely ‘Clock’ squatters, I would say – people who really commit to watching it!” Comer laughed.

But Marclay insists the point isn’t to see all of it; it’s more to make you hyper-aware of the time you’re spending literally watching a clock. “Here, you’re reminded that you have an appointment at a certain time, that you can’t spend your whole day watching this thing,” Marclay said. “You’re more than a viewer. You’re a participant in a way, because your life infringes on this clock.”

For more info:

Story produced by Julie Kracov. Editor: Chad Cardin.

Source : Cbs News